As Salone del Mobile opens this week in Milan, Memphis mania returns – spanning archival revivals, global exhibitions, and artistic homages.

By William Van Meter

When the radical design collective Memphis Group made its bombastic debut at Milan’s Salone del Mobile in September 1981, it delivered a brash retort to the ascendant minimalism of the era. Geometric shapes, clashing colors and patterns, and anti-functional forms embraced humor, utilitarian materials, and utopian ideals. It was a polarizing moment—one whose trickle-down effect would become a torrent, shaping the look of the decade and continuing to resurface in both new and familiar forms, decades on.

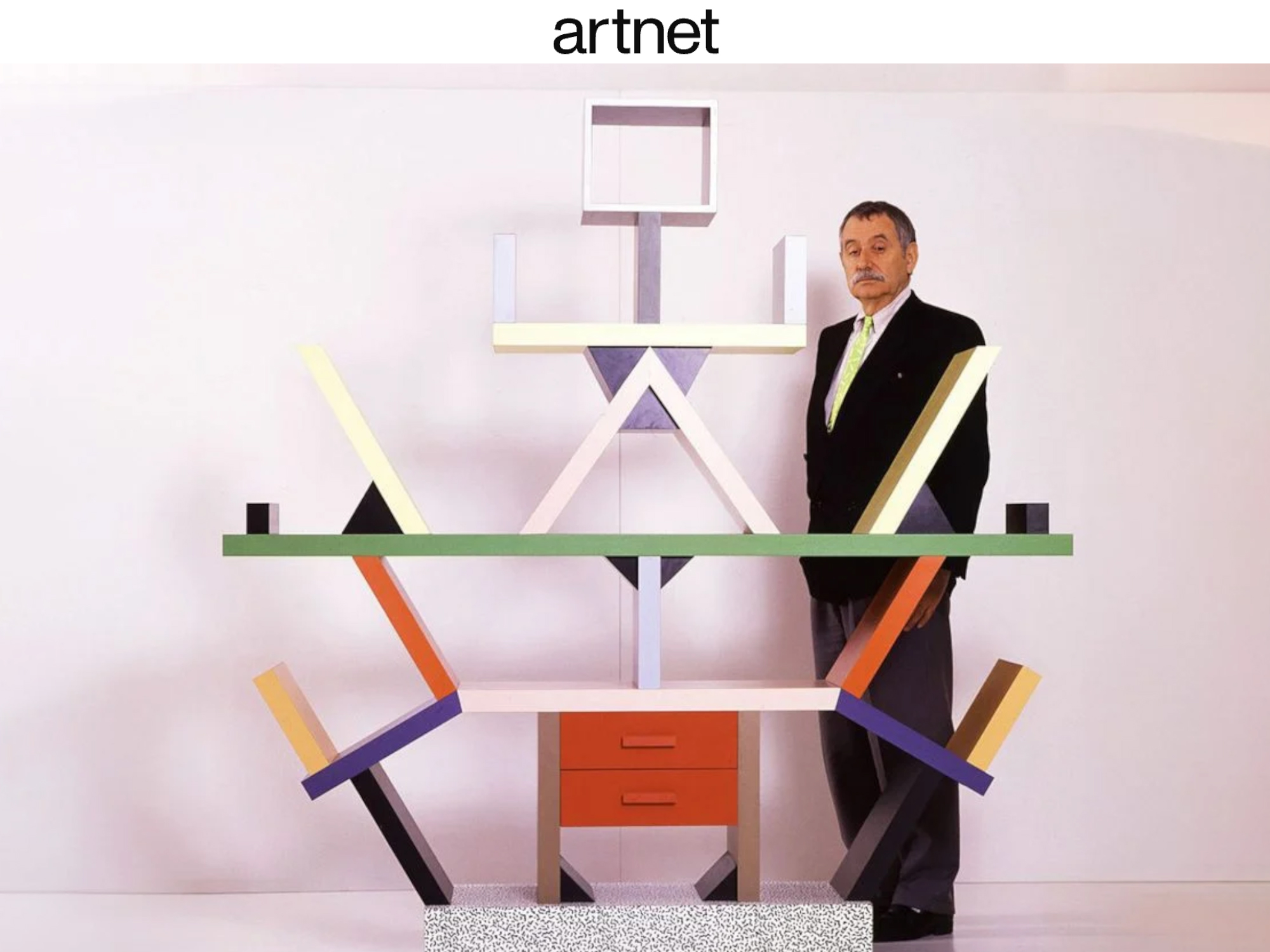

Its de facto leader, Ettore Sottsass, was no ingénue and well-versed in unorthodoxy. Unlike his younger collaborators, Sottsass was in his sixties. He had a decades-long career behind him—and a formidable one ahead. Even after Memphis fizzled by the end of the decade, he remained a force in the design world, his influence only deepening over time. But Memphis remains a defining chapter in the lore of Sottsass. In fact, many of his post-Memphis pursuits are erroneously lumped in with those of his former cohort. It all goes back to that 1981, love-it-or-loathe-it debut.

“Memphis emerged with disruptive force during a time of great transformation,” said Charlie Vezza. “The turbulent years of the ‘Milano da bere’ era, like a movement born from the energy of revolution.” Vezza is the 39-year-old CEO of Italian Radical Design, which acquired the brand and tweaked the name to Memphis Milano in 2022. He’s one reason that during this, the centenary of Art Deco, the squiggles and triangles of Memphis seem to be everywhere, including at this week’s Salone, where the brand is showing a mix of archive and never-before-produced pieces, like Sottsass’s “Venezia” table, christened after the city where he met Barbara Radice—his Memphis co-conspirator (she maintained its editorial voice) and life partner—at the Biennale in 1976.

But don’t call it a comeback—or even a return of a return. It’s more like Memphis is completing its fifth orbit around the sun. After falling out of fashion in the ’90s, it was reassessed in the 2010s through major exhibitions and canonized by institutions, gaining new critical appreciation and moving from ironic revival to mainstream embrace. The bold, graphic forms translate perfectly in the age of TikTok and Instagram, where design is consumed visually, and virality favors the playful and unexpected.

Pattern Recognition

We’re now knee-deep in the vortex of Sottsass mania. There are various exhibitions and auctions across the globe, and even a deadstock trove of Sottsass’s whimsical Memphis “Enorme” telephones were sold at last week’s invite-only design fair, Design.Space in Los Angeles (which also featured a Memphis Milano room along with a slate of Memphis-inspired programming and lectures).

For whatever combination of reasons it comes back, Memphis seems to rear its pastel head during times of strife or upheaval—like an antidote to anxiety. “There hasn’t been a specific contemporary event that reignited interest in Memphis, but I believe today’s reality feels just as bleak as the period that preceded its birth,” noted Vezza. “I sense the same yearning for joy, the same desire to escape the grayness.”

That longing for levity, for radical color and form, may help explain why Sottsass’s legacy continues to resonate so vividly. “Both Memphis and earlier movements like Art Deco were born out of moments of flux—periods of uncertainty and radical political change. There’s always a curiosity during those times for new aesthetics,” said Marc Benda, co-founder of Friedman Benda, whose gallery has staged more than 20 Sottsass exhibitions since 2003.

“If somebody’s never heard anything about design and wants to know who Sottsass was,” he said, “I usually boil it down to this very simplistic sentence: Sottsass was to design what Picasso was to modern art. He touched on every medium. You’ll always recognize his work—it’s idiosyncratic—but he was never pinned down to a formula or a framework. He worked on objects as small as an ashtray and on large-scale architectural developments. You can’t reduce him to a single catchphrase. He lived through, and responded to, the major moments of design history across six decades.”

At last month’s massive TEFAF in Maastricht, a fair that proudly spans “over 7,000 years of art history” and an airplane hangar’s worth of wares, the kaleidoscopic glassware of Ettore Sottsass still managed to stand out. The Friedman Benda solo booth was dedicated to Sottsass and featured everything from a fiery amber cylindrical Memphis prototype from 1983—wrapped in an indigo spiral—to some of his final experiments with color and form before his death in 2007.

Now, Friedman Benda is presenting “Et Tu, Ettore” at Galerie56, a focused survey of Sottsass’s cross-disciplinary work, ranging from rare early ceramics to late-career sculpture, on view through May 10. Cresting with Milan Design Week is “Ettore Sottsass. Architectures, Landscapes, Ruins,” an exhibition at Triennale Milano that closes April 13.

“Memphis was almost a return to a Bauhaus approach—a collective of designers and artists working across textiles, ceramics, furniture, and architecture,” said Abraham Thomas, the curator of modern architecture, design, and decorative arts at the Met. “It was an extremely rich roster.” That collaborative spirit, he noted, was also indicative of what was happening more broadly in the 1980s. “There was a kind of freedom in breaking across disciplinary silos—fashion designers, artists, industrial designers—working not necessarily under one banner, but sharing a sensibility. That moment in the ’80s felt rich with cross-pollination.” He sees a corollary in the 1980s London scene, where figures like Tom Dixon, Ron Arad, and George Sowden were similarly merging subcultural energy, design, and music into something radical. “It maybe looked different from Memphis,” he said, “but the energy was the same.”

“That spirit of boundary-blurring collaboration,” he added, “is precisely what designers today are channeling anew. There’s a whole new generation—especially in the U.K.—drawing on Memphis. People like Sam Jacob, Morag Myerscough, and Adam Nathaniel Furman are using color and pattern in ways that feel joyful but also culturally specific. Furman, who has spoken eloquently about this movement, coined the term “New London Fabulous.”

Karl’s Kingdom

Karl Lagerfeld was enamored with the watershed Memphis debut. “It was love at first sight,” he would tell a German fashion magazine in 1983. “I had just got a big apartment in Monte Carlo and had no idea how to furnish it. I had never lived in a modern building. I wanted it all modern and instantly thought that Memphis would be the Art Deco of the ’80s. I was right.”

Lagerfeld bought the entire 55-piece collection for his austere, gray bachelor pad in the Gio Ponti-designed Le Millefiori tower. What he felt the apartment was lacking, he commissioned the nascent group to create.

In “Francesco Vezzoli presents: KARL GOES TO MEMPHIS Tribute to a historic encounter in Monte Carlo,” the Italian artist recreates Lagerfeld’s home, with help from the modern-day Memphis Group. “This is my artistic documentation,” Vezzoli said last week by phone from his home in Milan. “It was a story that needed to be told.” The exhibition runs through May 24 at Almine Rech’s Monaco outpost.

“There is the element of my love and passion for Memphis,” Vezzoli said. “On the other side, there is Lagerfeld’s choice which is rather unique in 20th-century history of design and fashion. I cannot trade track down an episode of equal impact, probably when Halston commissions Paul Rudolph to renovate the townhouse. But that is a more common, like client-architect. This was a person that decided to live completely immersed in the imaginary world of the last avant-garde group of architecture of the 20th century. It’s something much deeper, much more radical, both from the side of the Memphis geniuses and Lagerfeld’s commitment to their creativity.”

The show is rounded out with Vezzoli’s depictions of different iterations of Lagerfeld’s myriad personae throughout the decades in dialogue with each other, his characteristic sewn tears adorning these composite images. Vezzoli sees Lagerfeld’s abode as more than just décor. “This is gay liberation before all the acquired rights of the last decades,” he explained. “Gay men lived mostly without families and were the only person in charge of his environment. This is one of the great episodes of the 20th century where an eccentric homosexual figure projects his identity into architecture.”

The installation isn’t just a kitschy step into a quirky bachelor pad. There is also a dark, Pompeii-like venture into a place of sexlessness and sadness. It’s a journey into a void, a space that no longer exists.

Echo Effect

The Tawaraya is perhaps the most iconic, and certainly the most outlandish, creation of the Memphis Group: a hybrid bed, above-ground conversation pit, and sculptural installation by the Japanese designer Masanori Umeda in 1981. It’s a platform for life—and architect Kulapat Yantrasast has three of the originals.

One of Yantrasast’s Memphis boxing rings resides in his Los Angeles home, serving as a personal reading den, while another sits right at the entrance to the New York office of his architecture studio, WHY. There, it acts as a kind of ceremonial meeting space. “The one in New York is used as a kind of powwow,” he said. “We spend hours in there, almost like a tea room. It has this sense of concentration, of being relaxed, but also a sense of intimacy.”

His third is currently in storage. “I don’t really know what to do with it yet,” he said. “But I had to have it.” A few of his Memphis pieces came from Lagerfeld’s legendary auction.

Yantrasast has been a Memphis acolyte since seeing an exhibition in Japan when he was in graduate school, first encountering the movement through the work of Shiro Kuramata. He sees its enduring appeal today. “Design doesn’t seem to really have a sense of ideology today,” he said. “It’s become about communications and other things, and so people are now looking back at when design had a point of view, and in this case there’s a sense of humor and humanity. It’s integrated art and design. There’s a sense of not quite hippy, but liberalism that people are looking for from something that’s authoritarian and very ordered.”

Yantrasast has witnessed the meaning of Memphis objects shift over time. He points to the 1986 dark comedy Ruthless People, where Memphis design signaled theatrical excess, unapologetic taste—or something much worse. “It was the opposite of the American dream,” Yantrasast said. “They were basically these Leo Castelli–Illeana Sonnabend figures—so powerful and so artsy. And they live in this house where everything is Memphis, even the bedroom.” That aesthetic extremity, he noted, carried a certain cultural charge. “It was like how the villains in those James Bond films always live in these ultra-designed houses—like a John Lautner house, right? That kind of vibe. It was a signal that these were not normal people who go to church.” At the time, he said, that connotation may have kept Memphis from breaking fully into the mainstream. “It quickly got swept up into the postmodern wave—and then disappeared. But it had a deeper impact than people realized.” For Yantrasast, the reemergence of Memphis isn’t a revival so much as another turn in its ongoing orbit. Its spirit, he believes, never truly vanished. “I think that, in a way, it’s never gone away.”