By Pei-Ru Keh

American multidisciplinary artist Daniel Arsham presents ‘Objects for Living: Collection II’ with Friedman Benda (30 August – 25 September 2021), a new series of hand-sculpted furniture in a combination of wood, resin and stone.

The prolific multimedia artist Daniel Arsham may be synonymous with his Future Relic series, which casts ubiquitous objects, such as Pokémon, supercars and sneakers, as historical artefacts, calcified, eroded and unearthed a thousand years from now. But it’s his new additions to a line of furniture that are currently stealing the limelight.

This follow-up effort was developed off the back of his debut furniture collection from 2019, Objects for Living, which the artist exhibited at Design Miami that year with New York design gallery Friedman Benda. It sees Arsham continue his exploration of structural, material and, of course, temporal contrasts in a truly functional form. The new pieces, which include lighting, a sofa, and a dining table and chair, are being presented as part of Arsham’s first solo show with Friedman Benda (30 August – 25 September 2021).

Arsham’s foray into furniture design is no surprise. He studied design and architecture in high school in Miami, but then pivoted to art at the Cooper Union in New York after he wasn’t accepted into its architecture programme. Arsham’s long-standing interest in design continues to be evident in his involvement in Snarkitecture, the multidisciplinary practice he co-founded with Alex Mustonen in 2007. The firm is known for its pioneering spatial interventions and immersive experiences for celebrities, brands such as Cos and Lexus, and real estate developers including Related Companies and Central Group, often realised in its signature greyscale palette.

Objects for Living emerged from Arsham’s desire to create pieces to fit his weekend home on Long Island, a modest yet distinctive bungalow designed by American architect Norman Jaffe in 1971, which the artist acquired in 2017. Inspired by Jaffe’s juxtaposition of curves and angles, Arsham designed several armchairs, a desk, a floor lamp and a rug for his personal use within the house. This inevitably caught the eye of gallerist Marc Benda, who saw the merit of revealing this other facet of the artist’s practice to the public.

Although some of the pieces from the inaugural series subscribed to Arsham’s distinctive fossilised aesthetic, others took on more organic, assemblage-like forms, which is the direction Arsham has expanded in for this second iteration, a reflection of the extensive time he spent at the house with his young family during the pandemic, along with the types of pieces he wants to live with.

‘Most of the design for this happened during the lockdown in New York,’ Arsham recalls. ‘I had gone out to the house in early March and I didn’t really have a lot of materials or things there with me. I started sculpting with Play-Doh, which my boys had loads of, and started modelling different types of forms. I wasn’t thinking that those would be the final forms, but I let them dry and when we came out of lockdown, I ended up just getting them 3D-scanned.’

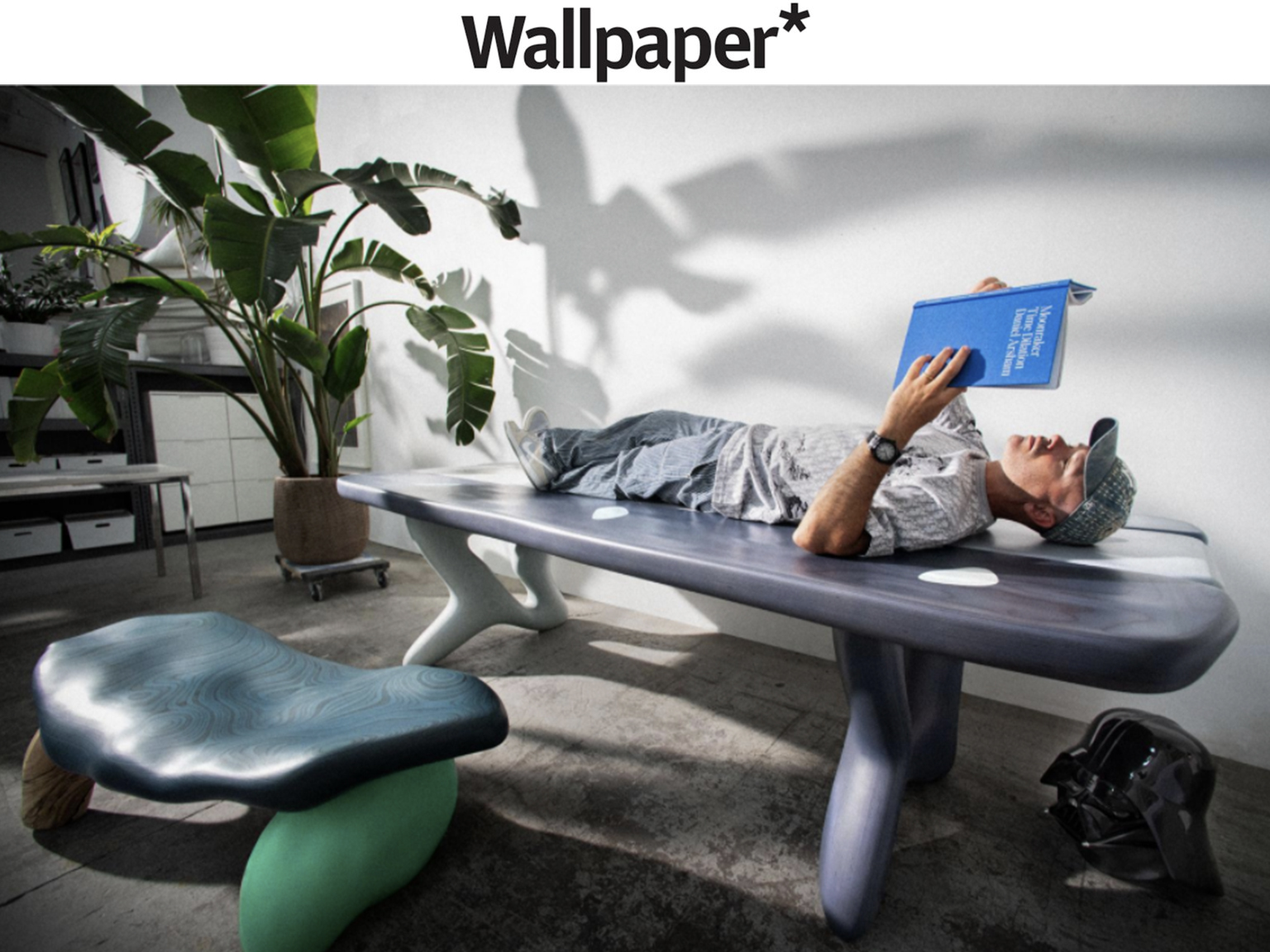

Each piece’s hand-formed components retain all the idiosyncrasies of sculpting in Play-Doh, from the rough edges and indentations on the back of an armchair to the organically-shaped legs of the dining table. Realised in a combination of wood, resin and stone, each sculptural piece has a naive, almost primitive appearance that taps into Arsham’s fascination with blurring and warping time, albeit without the usual archaeological overtones.

Materials and Manufacturing techniques

‘There’s a material difference between the two collections. Most of the first collection was [made from] resin and sculpted digitally,’ explains Arsham. The new pieces express ‘a material transformation. There are pieces that are solid stone, solid resin and then hollow resin, where you see the light push through it. There’s also this wood technique that we’ve been using in the studio that gives all of these amazing patterns.’

‘I want these things to actually be used. They’re not sculptures that won’t be touched’ – Daniel Arsham

Deployed on the seat of a chair, for example, the technique produces a boisterous wood grain that mirrors the topography of the sculpted wood. ‘I achieve this variation by laminating the plywood, tilting the whole thing on an axis, then milling it as if it was flat,’ he says. ‘Once you start milling, you get these patterns that are impossible to predict because of the angle of the grain.’

Visual appeal aside, Arsham has also focused on the comfort and practicality of each piece, inspired by the balancing of form and function in Wendell Castle’s ‘Triad’ chair (2006), which sits in his studio. ‘I usually start with the chairs because they are the most generic form. Once I had everything sculpted, we milled it in foam and then I changed the scale and pitch of things for ergonomics so that it actually feels comfortable,’ he says. ‘When you sit in the armchair, your body fits in it correctly. I want these things to actually be used. They’re not sculptures that won’t be touched.’

A highlight of the new ten-piece collection is an ambitious bed frame, which Arsham conceived for the Brooklyn brownstone that he purchased last autumn. ‘I still just have a mattress on the floor because I’m waiting to finish this bed,’ he laughs. ‘Every single thing that I want in a bed is in this, from the storage underneath to the charging ports and reading lamps; it has underlight, it has backlight and a task light. The way the light feels is based on different conditions.’ Some details were inspired by Arsham’s stays at hotels in Asia: ‘There’s a small bench on the end of it that you can sit on if you’re putting your socks on. It’s a very whimsical design.’

With a headboard formed by individual organic shapes, the asymmetrical bed facilitates an interplay of light and shadow that transforms it into a sculptural art piece. ‘The wall that it will sit on doesn’t need anything else. I don’t have to put an artwork on the wall because the bed becomes that,’ Arsham adds. Completed with recessed drawers that are concealed from view, nightstands on either side that are integrated into the overall form, and reading lights that can be tucked away, the low bed frame cuts a strong yet seductive figure.

‘As abstract as some of the first designs were, I shaped the pieces to fit the body perfectly, even if they looked like the most uncomfortable things ever. There’s a counterintuitive thing you can have with furniture,’ Arsham explains. ‘With artwork, sometimes the visual quality of the thing is different from what it makes you feel or what it means. With furniture, or design objects that you actually touch, there’s a different level of possibility in the contrast between how it looks and feels. Even though this collection has things that are very playful, I really spent a lot of time on the ergonomics, to make sure they work for what they’re supposed to do. Every single thing that I’ve designed furniture-wise, I designed it with the intention of using it.’ §

INFORMATION

‘Daniel Arsham: Objects for Living: Collection II’ runs from 30 August – 25 September at Friedman Benda, New York

friedmanbenda.com

danielarsham.com

ADDRESS

515 W 26th Street

New York

NY 10001

USA