By Robin Givhan

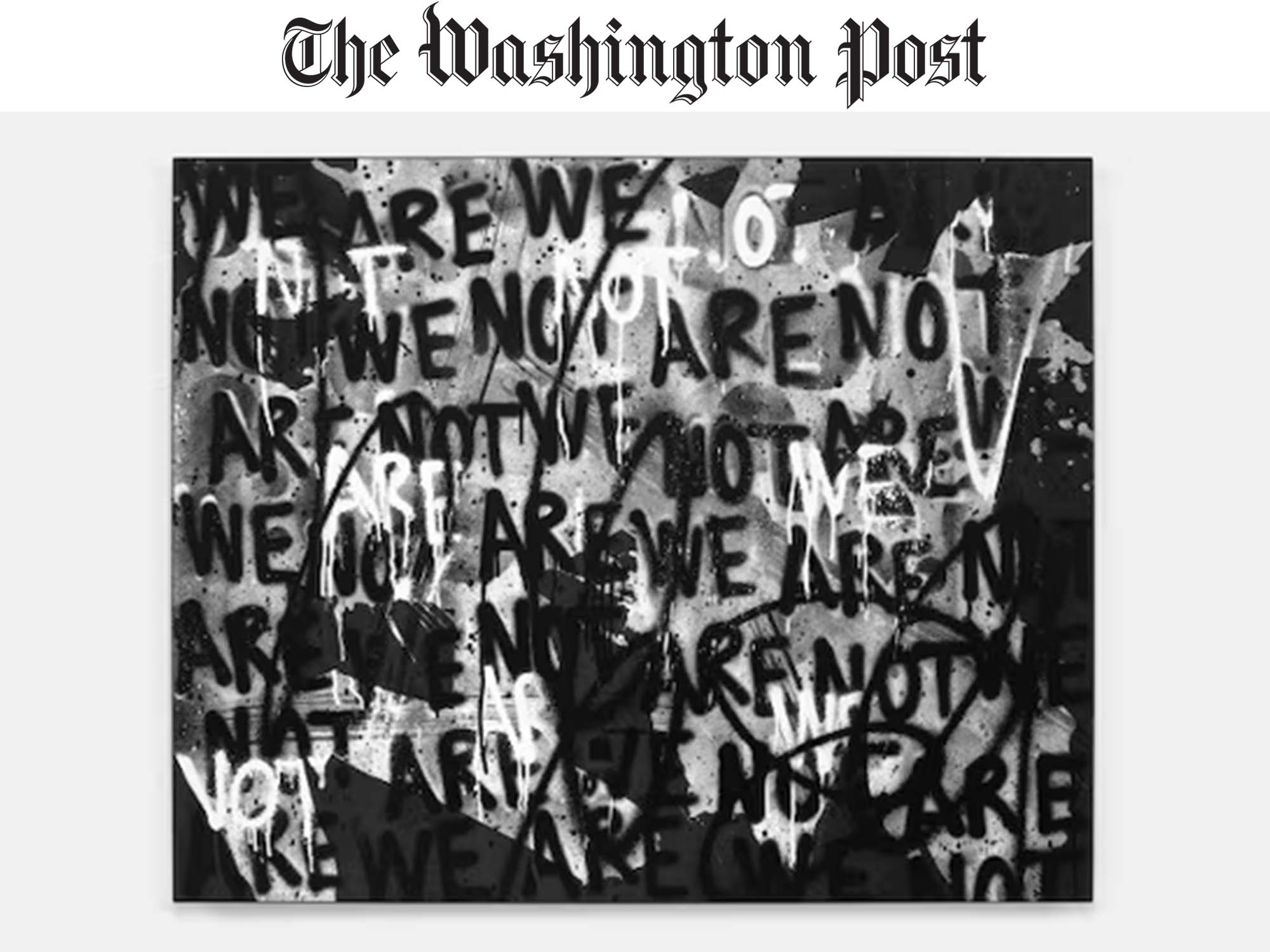

‘If we do not stop this madness, we will destroy ourselves and the whole world,’ artist Adam Pendleton’s “Resurrection City Revisited (Who Owns Geometry Anyway?)”

Of all the museums that make up the Smithsonian Institution, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden is the one that speaks most directly to the times in which we live. If the other museums seek to consider the country’s past with both delight and sobriety, the Hirshhorn leans into the future through the lens of contemporary art. Its exhibitions are an invaluable and invigorating counterpoint of a president working to rewrite the history of the country through executive orders and hostile takeovers of cultural institutions.

President Donald Trump has expressed a hysteria about the past, about things that have happened, rather than trying to acclimate himself to the wonders of life in the present. Most recently, he has issued an executive order, in which he decrees certain unavoidable and necessary truths to be dangerous and dispiriting.

“Over the past decade, Americans have witnessed a concerted and widespread effort to rewrite our Nation’s history, replacing objective facts with a distorted narrative driven by ideology rather than truth. This revisionist movement seeks to undermine the remarkable achievements of the United States by casting its founding principles and historical milestones in a negative light,” read the executive order. “Under this historical revision, our Nation’s unparalleled legacy of advancing liberty, individual rights, and human happiness is reconstructed as inherently racist, sexist, oppressive, or otherwise irredeemably flawed. Rather than fostering unity and a deeper understanding of our shared past, the widespread effort to rewrite history deepens societal divides and fosters a sense of national shame, disregarding the progress America has made and the ideals that continue to inspire millions around the globe.”

Trump then commanded the vice president go forth and make history more pleasing to him.

The Hirshhorn is a place to find a real-time retort by both intention and happenstance. Fear, possibility, hope and frustration — the emotions of the here and now — live on its distinctive curving walls. The cultural conversation at the Hirshhorn is not one between elites, as many of the president’s most ardent supporters might have one believe simply because the museum is situated within an East Coast, liberal landscape. Like its sister Smithsonian institutions, the entrance is free. The Hirshhorn’s doors are flung wide to all. It’s a place where average folks can wander in whenever they want and strive to make sense of the complexities of life.

On Tuesday morning, the artist Adam Pendleton was at the Hirshhorn to preview his first solo exhibition in Washington — a show that simply asks viewers to think, and refrains from telling them what to think. “Adam Pendleton: Love, Queen” opens April 4, and while it has been years in the making, it speaks to this moment, not because it delves into political polarization, the president’s petulance or because it tests the strength of our democracy, but because it transforms the emotional slurry of upheaval, estrangement, hope and confusion into images — into something that can hold a visitor’s gaze and be inspected.

“This work is not about quick looking,” Pendleton said as he introduced the exhibition. “It’s about deep, thoughtful engagement and using your imaginative potential.” This is a country that needs to exercise that muscle: imagination. Much of the electorate has been stunned by the actions of this White House — the tariffs, the dismissal of due process, the revenge, the posturing in front of half-naked prisoners as if they were little more than inanimate props — not because of a lack of information before Nov. 5, but because of a failure of imagination.

Pendleton, who was born in Richmond in 1984, is an abstract artist, and no small number of his works are untitled. They evoke mood and memory. The layers of material and color on canvas can conjure up calm or discomfort, sometimes both. They can make people feel as if they’re viewing the aftermath of violence or the prelude to serenity. “Untitled (WE ARE NOT)” leaves a person caught between the tension of feeling fully seen and wholly dismissed. Its messy script reads: We are not. Are we. Not. Not are. The large works referred to as “Untitled (Movement)” suggest glints of light in the darkness. Or darkness consuming the last sparks of light.

The exhibition closes with a floor-to-ceiling video, “Resurrection City Revisited (Who Owns Geometry Anyway?)” — a strobing, chaotic series of images from the encampment erected on the National Mall in 1968 as part of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Poor People’s Campaign.” The documentary video is overlayed with flashes of triangles and circles that sometimes blot out the faces of the activist, sometimes creating a nimbus behind them.

The camera sweeps through trees. It captures the grainy image of birds in the sky, of shanties under construction or being torn down, of monuments to democracy, of watchful police officers, of citizens marching up the steps to the Office of the Attorney General. Of all the faces, one of the most compelling is that of a little Black boy. He appears about halfway into the nearly 10-minute video. He looks directly into the camera with a solemn expression and wide eyes. And one wonders: Did his dreams come true?

The images are vintage and so are the disembodied voices, but the story remains contemporary. Fretfulness over gun violence. The dissatisfaction with the status quo. The desire for the government to do better. “We have come to Washington for our freedom. We have come to Washington for justice. We have come to Washington for jobs,” a voice intones. “I hope this march to Washington will be successful simply because I think this will be the last chance America will have to rectify the mistakes its made through the ages.”

And what if those words from that era are true? Has America missed its last best chance? What if Washington cannot provide jobs or justice or freedom? What to do with a White House that isn’t interested in rectifying the mistakes of the past, but in blotting them out? The artwork doesn’t answer these questions; it simply poses them to the people who have come to contemplate the here and now.

The video ends with an Amiri Baraka poem in which he quotes jazz musician John Coltrane, “I want to be a force for real good.” At the Hirshhorn, an artist considers the past, but leans into the future. The People can choose to do the same.