“Ceramics support everything – the old, dry gentle terra-cotta bears all things. They bear culture, as ethnologists say, societies, people, kingdoms, sultanates, and even empires.”

“The fact is that empires can also be reckoned on the color of ceramics.”

— Ettore Sottsass, 1962

On November 5, Friedman Benda will open Antichi, the third in a cycle of exhibitions devoted to the expansive oeuvre of the iconic architect-designer Ettore Sottsass [1917-2008]. Designed in 1989, Antichi comprises a series of 14 architectonic ceramic works executed in deeply saturated hues, and titled for ancient cities. Antichi have never before been shown in America. The exhibition will be open through December 19, 2009.

Antichi are named primarily after cities in today’s middle east, after mythic empires, with complex histories within the cradle of civilization. Some works, such as Babilonia, Gerico, Samarra, and Susa refer to those biblical cities and therefore, have Judeo-Christian significance but others, as Ninive and Kerman, reference cities of worship for Zoroastrian and later Assyrian gods. Most significantly for Sottsass was that these empires left behind ruins and objects that reflect the origins of writing, religion, society, and spatiality between people and their environments.

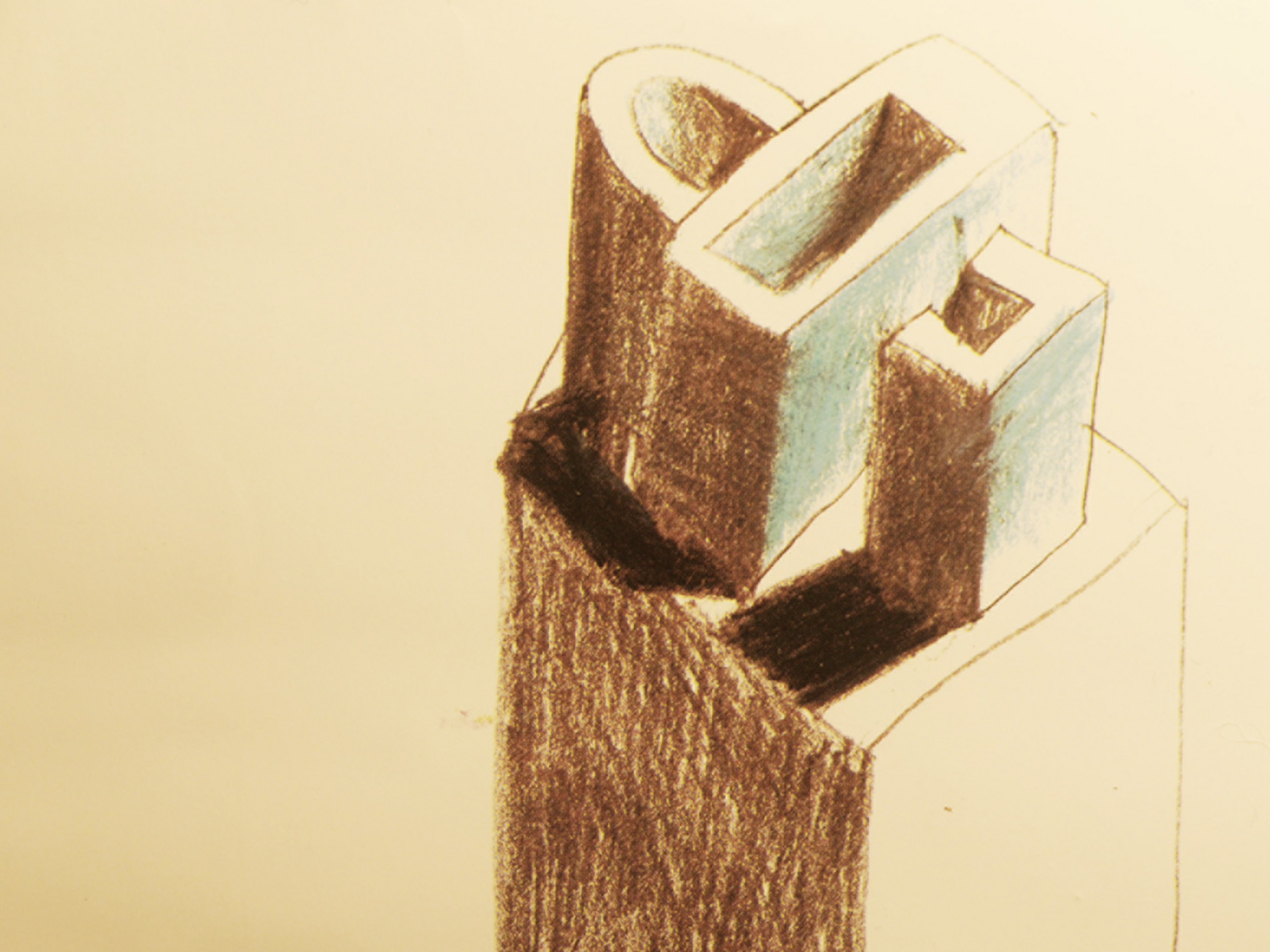

With Antichi, Sottsass uses abstract geometries, resembling ideograms, to comment on the ways that ancient architectures inhabited the rituals and movements of daily life and the greater mysteries and rhythms of the cosmos. As such, these works reflect Sottsass’ life-long pursuit of an elemental language: a series of signs, that together would articulate sweeping worldviews; not intellectual or rational but sensorial and instinctual, eliciting fantasy or open-ended dreams. The material for his evolving body of work often came from the unpredictability of his experiences in distant lands.

The influence of ancient cultures on Sottssas’ lexicon of design was very apparent early in his career. By 1960, he had already designed the entrance hall of the 12th Triennale in Milan, followed by a seaside villa in 1961, that incorporated a series of symbols and forms derived from Sumerian architecture. Furthermore, his plans show what was thought of as a violent introduction of color, indigenous to the Mediterranean cultures he had visited.

Sottsass’ restless nomadism led him to wander far from Italy at seminal moments in his life to India, Ceylon, Nepal and Burma in 1961, Greece, Spain and Israel in the 1970s, and New Guinea in years after. The knowledge gleaned from travel was continually augmented by his private gathering of information, whether through objects or literature, relating to ancient cultures. He called this his “existential tourism.”

As with the Antichi ceramics, Sottsass’ references to architecture were always predicated on ideas and impressions. Early on, he lauded the practitioners of neoplasticism as the “first to raise architecture to a pitch of artistic intensity.” Looking at his New York temperas from the 1950s, Sottsass depicted the frenetic metropolis as an exciting and exotic landscape through simple agglomerations of signs, lines, patterns, and plays of voids and solids. Throughout the entirety of his career, from these early paintings to the photography of the 70s, and later works of architecture during the 1980s, Sottsass used color to determine shapes within a composition and the relationship of exterior surface to interior function.

Sottsass made his first ceramics in 1956, at the request of the American businessman Irving Richards, who was seeking “modernistic” objects. The artist, in fact sought freedom from the “modern movement,” a pursuit that laid the foundation for his radical design group, Memphis, and contributed to the postmodern design-movement. Consequently, he made a group of ceramic work that failed to sell. Nonetheless, it began an important relationship with ceramics that was to last until his death. While experimenting with almost every known artistic material for another 60 years, ceramics remained his most deeply personal medium.

Of Sottsass’ work with ceramics, his biographer and widow Barbara Radice, writes:

Ettore loves ceramics but above all he loves the cultural idea of ceramics… He loves their antiquity, anonymity, and widespread popularity, their involvement with daily acts, their poverty and precious simplicity, their tremendous fragility, their warm hardness and the petrified perfection of their powder glazes when they come out of the kilns purified by fire.