By Lucy Watson

“Today”, says the blurb for the exhibition Here We Are! Women in Design 1900 — Today at the Vitra Design Museum, “we take it for granted that women have successful careers in design”. That wasn’t always the case. So far so obvious. But women have had careers in design: the issue, the exhibition makes clear, is that they are often not remembered as successful and are absent from accounts of design history.

That was something that the Vitra furniture company discovered, says curator Viviane Stappmanns, when it spent 20 years putting together its Atlas of Furniture Design, published in 2019, based on its vast collection of more than 7,000 items of furniture and 1,000 pieces of lighting. The company was founded in 1953 when Willi Fehlbaum discovered furniture designed by the husband and wife duo Charles and Ray Eames on a trip to the US and decided to manufacture the pieces for the European market.

Now holding licenses to produce some of the most well-known designs from the 20th century, including Verner Panton’s 1967 cantilevered plastic chair and Isamu Noguchi’s 1944 sculptural wood and glass coffee table, you might think that what Vitra doesn’t know about furniture isn’t worth knowing. One of Vitra’s bestselling products, the much-imitated, 1956 bent-plywood lounge chair by the Eameses, might be partly designed by a woman — but, “once you start putting it together you realise there are gaps,” Stappmanns says. “We thought, where are the women designers?”

The show collates the work of more than 80 women designers and their disparate work through the past 120 years — beginning in 1900 “when design emerged as a profession in its own right,” Vitra says — in order to “redress the balance”. The exhibition takes place near the small German town of Weil am Rhein, near Basel, at the Vitra Design Museum — a modestly sized but eccentric 1989 deconstructivist building by architect Frank Gehry, part of the Vitra “campus” along with the factory where the products are made.

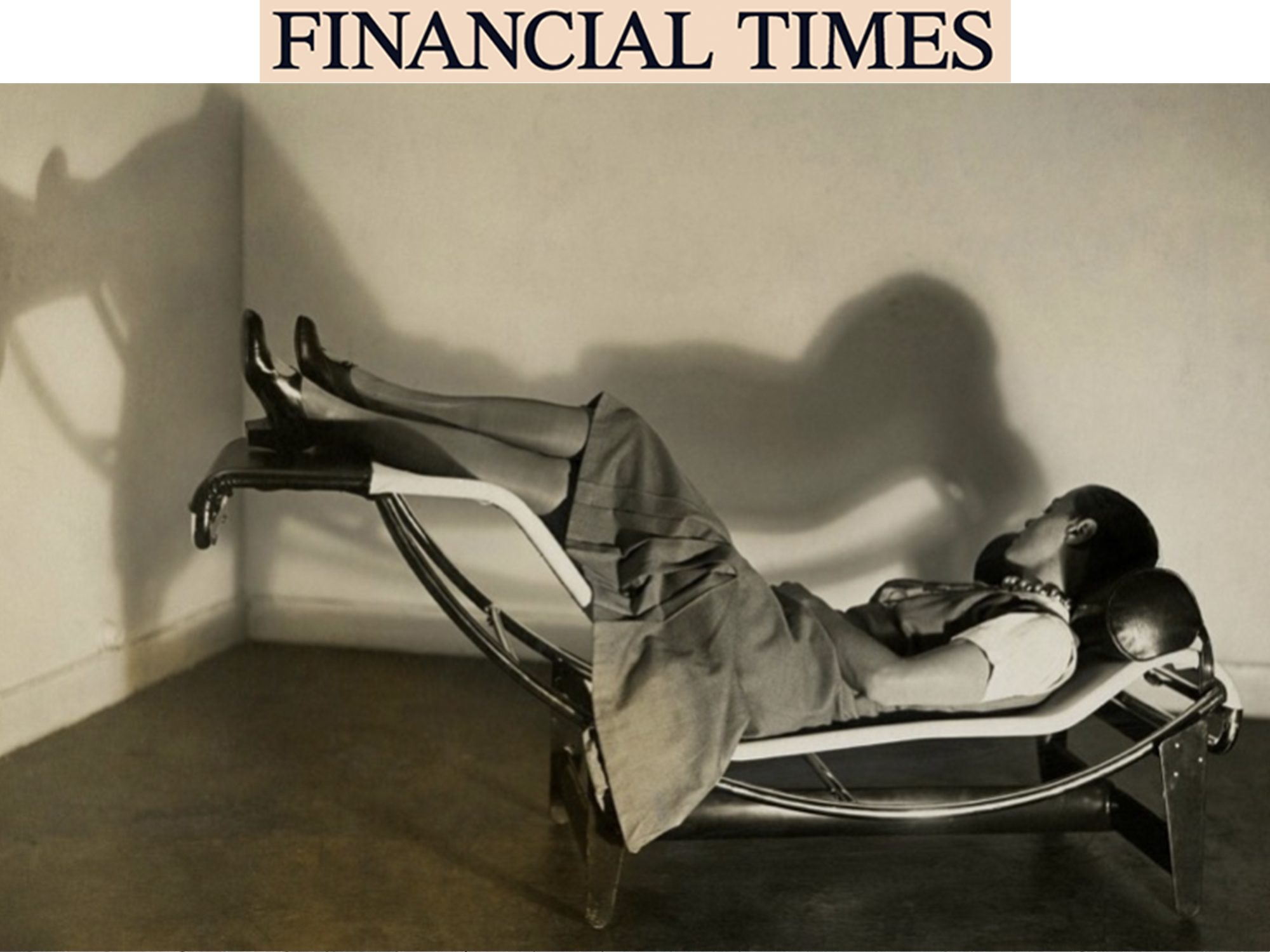

In the gallery, obscure early social reformers are joined by Bauhaus students, now lauded but then little-known mid-century names — Charlotte Perriand, Eileen Gray, Ray Eames and more — and contemporary creators such as Patricia Urquiola and Faye Toogood.

This is not just a corral of designers with little in common beyond their gender. Works are grouped by period — 1900-20, 1920-50, 1950-90 and 1990 to the present day — but the approach is the same regardless of year. Questions are posed about the structural reasons behind the dominance of men in the field. What is historically considered to be “design”; what role does access to education, peers and mentors have in a designer’s career; and how does the administration of new products shape the course of design history.

“Once you start putting it together you realise there are gaps. We thought, where are the women designers?” – Curator Viviane Stappmanns

As architect Jane Hall writes in the recently published Woman Made: Great Women Designers, it is the “conspicuous omission of women, rather than their presence” that has shaped what we know about women’s role in design history. “Even those partnered with famed men struggled for visibility”, she writes.

Many designs, even what we now consider to be classics, are attributed to men even if that were entirely not the case. Lilly Reich was already a successful architect and designer, and the first female board member of the Deutscher Werkbund (German Association of Craftsmen), when she met collaborator Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in the 1920s. His 1930 Barcelona daybed is still manufactured today and sold under his name. But it is her design, evidence suggests.

They were close collaborators. “Mies did nothing without first speaking to Lilly Reich”, says one associate that architect Gill Matthewson quotes in a 2002 paper. In contrast, Mies van der Rohe’s attitude towards collaboration was this: “when an idea is good and it is a clear idea — then it should only come from one man.”

While Charlotte Perriand was alive her work was obscured by her association with Le Corbusier. The red leather B302 swivel chair, designed by Perriand in 1927 for her Paris apartment before she met the architect, is now sold as the LC7 (no prizes for guessing what that stands for) and attributed to “Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand”. The first time Perriand visited Le Corbusier’s studio, he turned her away, saying, “we don’t embroider cushions here”.

For many designers, work was often unsigned, unattributed or not kept in one place. Patents could be difficult to obtain or registered in a husband’s name — ensuring that the creator is forgotten or, at the very least, difficult to trace. Once a work is attributed to a certain name, it takes a huge amount of persistence to change that. Who knows what notable figures haven’t had families, scholars or museums to push for attribution? “If nobody cares for someone’s legacy then nothing happens,” says Stappmanns.

The hurdles begin much before women have the chance to produce anything, though. Historically “universities just wouldn’t admit them.” If, says Stappmanns, “they’re not educated together, [then] they’re not registered as professional designers and they slip through the cracks”.

In the 1920s that began to change, sort of. The Bauhaus, the influential German art school founded by architect Walter Gropius in 1919, had so many women enrolled that it became worried about its reputation, says Stappmanns. Regardless of what they applied to study, women would be directed towards the supposedly feminine disciplines.

Gertrud Arndt, whose 1924 No. 2 rug is remarkable enough for Gropius to have displayed it in his office, wanted to study architecture but was forced into weaving. Her work isn’t included in the Vitra exhibition, but perhaps the most well-known of these women is Anni Albers. She applied to study in the stained glass workshop. But, she said in 1968, “the only thing that was open to me was the weaving workshop. And I thought that was rather sissy”.

Many of these women, once they had made it into the profession, would very easily drop out. Arndt gave up her work to care for her family. Toy and children’s furniture designer Alma Siedhoff-Buscher (also a Bauhaus weaving student before successfully applying to transfer to woodwork) was “very commercially successful”, says Stappmanns. But that didn’t stop her from also retiring to care for her family.

This wasn’t always voluntary: Gertrud Kleinhempel became the first female design professor in Germany in 1921 — her contract stated she would lose her job if she married. Little was known about her until a private collector approached Vitra and said they had 2,000 drawings by her. “You could do 10 PhDs on this and not be finished,” says Stappmanns.

The way that the industry and women’s work has historically been structured means that gender shapes the type of work made, and then, in turn, the type of work remembered or canonised. Work made for everyday homes (literally homemaking) is more frequently forgotten, less visible, less publicised and considered less important. “You think, oh there just weren’t as many women as men,” says Stappmanns. “But you find a lot of women that made contributions if you look beyond the classic places you would usually look.”

This is a common theme beginning to end: in 1909, Louise Brigham published Box Furniture: How to Make a Hundred Useful Articles for the Home, a book of designs and instructions for furniture made from packing crates for low-skilled householders. More than 70 years later, Matrix Feminist Design Co-Operative interrogated the “man-made environment”, designing centres for women and childcare, publishing A Job Designing Buildings: For Women Interested in Architecture and Buildings and opening technical training centres.

“Do women design any differently from men?” says Stappmanns, repeating a question she says she is often asked. “No, absolutely not. But you always design for where you are.”

Women’s work in design might have begun in the domestic sphere — but even beyond the stratosphere there were issues with recognition. Galina Balashova designed the interiors for Soviet spacecraft from 1963 and 1986. But her employers didn’t really know what she did — at one point while designing for the Mir spacecraft her official employment was as a security guard.

“So I was paid only for this work and all of my interior and graphic design projects were done unofficially and at no charge,” she says in an interview with Vitra curatorial adviser Alyona Sokolnikova. “During all those years, no one really understood or appreciated what I was doing there. It was as if I was just doodling for the fun of it,” she says.

Her designs included Velcro fastening systems and the use of light walls and dark floors to aid spatial orientation. There were homely finishing touches too: her watercolour paintings were included, but “perished when the orbital modules burnt up on the way back to Earth”, she says.

Structural issues about access to education and having to retire to care for a husband are not as immediately pertinent by the final room. But there’s still work to be done to address and rectify the lingering problems of the past in today’s practice. A 2021 project by Matri-Archi (tecture), uses weaving to portray the career paths of five female African designers, including sections named “Tests, threats, allies” and “The ordeal”.

And the scope of design needs to change. It should be for everybody. An armchair by Inga Sempé is also present: like Brigham, her work is domestic, not for the blockbuster architectural projects. “My designs are for people. And most people I know have small homes with small rooms, and they don’t live in castles and palaces,” she has said about her work.

The question remains today, as much as it did 120 years ago: who is “design” for? There are still issues today, out-of-date attitudes to be grappled with, a canon to rectify and work to be done: diversity, gender parity, pay gaps and more. The board in the final room reads, “Has our approach been too limited? Too Eurocentric, not sufficiently inclusive?” It’s reassuring that the museum, so physically close to the offices and workshops where the products are made, doesn’t consign the problems to the past. Maybe we can’t change what happened, but we can change how it is remembered.

As the museum says, “we still have some negotiating to do.”

“Here We Are! Women in Design 1900-Today” runs until March 6, design-museum.de