By Tiffany Jow

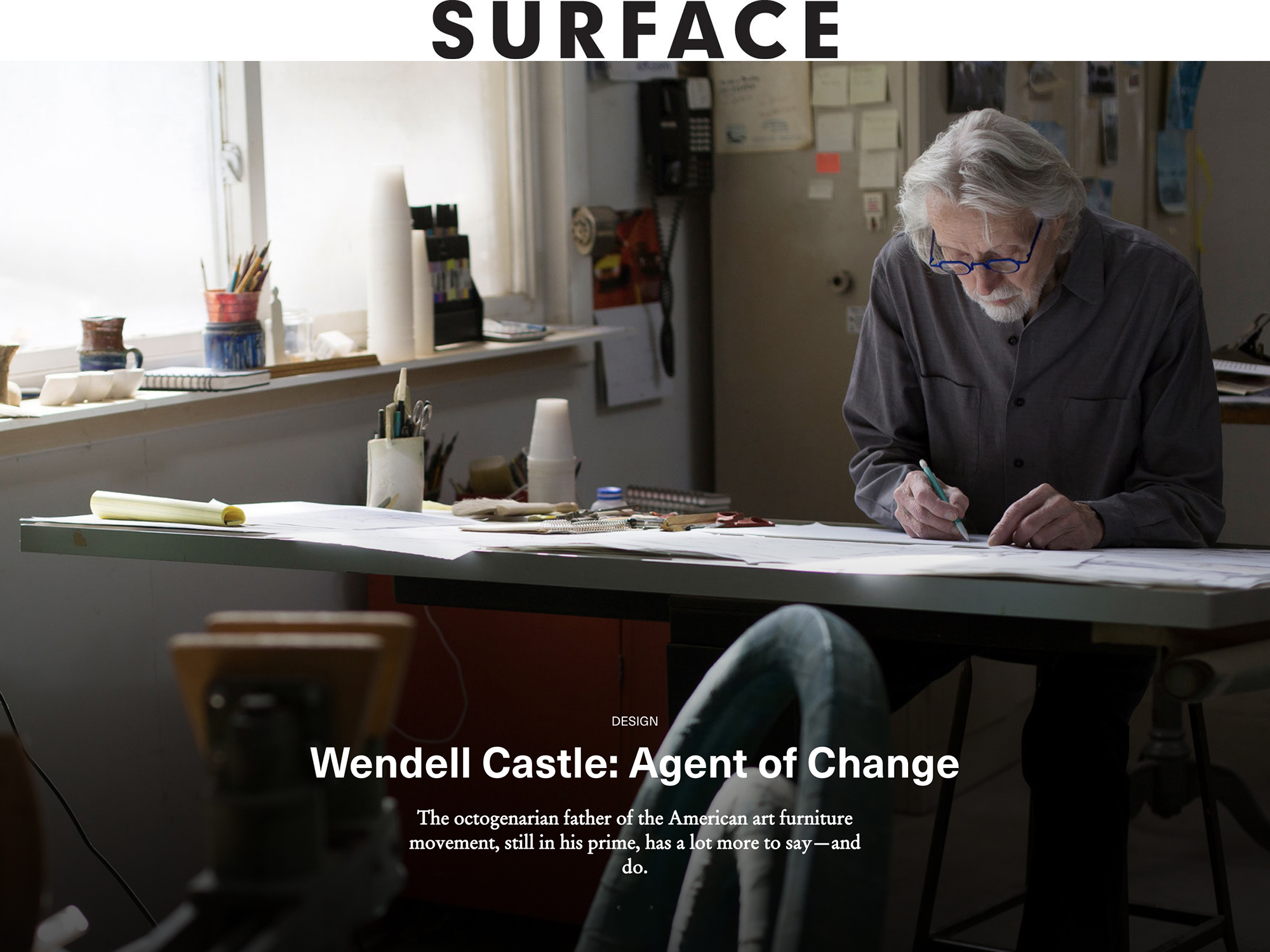

“I’ve had people ask what my real name is,” Wendell Castle says. It’s a laughable notion to anyone who knows the man, whose work is rooted in authenticity. As one of the first American designers to challenge the boundary between utility and fine art, Castle creates an enticing breed of objects marked by superior craftsmanship and ingenuity in form, style, and technique. His creative fuel consists of a wild imagination paired with the calm, steady work ethic of a Midwestern farm boy. It gives him the utmost pleasure to create a successful piece under his own terms: a once unthinkable concept of furniture that doubles as art.

Now in the sixth decade of his career, Castle pushes forward using a digital tool kit—complete with a robot—without abandoning traditional handmade craft. “Wendell is the most important postwar American furniture designer, by a long shot,” says Glenn Adamson, senior scholar at the Yale Center for British Art and the former director of New York’s Museum of Arts and Design. “He’s the only person of that generation with a deep connection to modernism who’s also working in this very technologically advanced way. He’s like a one-man time warp.

Castle’s newest exhibition, on view at Friedman Benda from June 22 through August 11, attests to his indefatigable verve. Its title, “Embracing Upheaval,” is a kind of Castle credo. “I like the idea of my mind being in upheaval,” he says. “Not that I want to be surprised, but I’m very happy not knowing where things are going.” He shows me a maquette of a seat sprouting from a ball-and-claw foot, part of an 18th-century chair he 3D-scanned. “Years ago, I never would have done this,” Castle says, grinning. “But, what the hell? I’m just trying to think in as many ways as I can.”

The show focuses on “Block” and “Freeform,” two new series made by stack lamination, a process that Castle pioneered in the 1960s. Layers of wood are glued edge to edge and then carved out to create lens-shaped seats perched on wiggly, trunklike bases. In a nod to his love of jazz, each is named for a city synonymous with the music. “Block” references Renaissance sculpture, in which a marble figure’s base is left unfinished, to support the weight. Castle interprets the method on a horizontal scale, so a seat, hovering in midair, extends sideways from its base via a joint covered in chisel marks. “I’ve been trying to figure out where the legs go,” Castle says. “They can go anywhere except the four corners—that’s not allowed.” Case in point: “Dante’s Heaven,” the exhibition’s lone cast-bronze object, consists of a bucket seat with legs grouped around its back like an array of unicorn horns.

In October, Rochester’s Memorial Art Gallery will present an expanded version of “Wendell Castle: Remastered,” which originated at the Museum of Arts and Design about a year and a half ago. Next year, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City and Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art in Overland Park, Kansas, will mount concurrent solo exhibitions for Castle, who has four honorary degrees, an American Craft Council Gold Medal, and work in more than. 50 institutions. It’s the latest in a surge of exposure for the notoriously humble designer. And despite his 84 years, he shows no sign of slowing down.