By Emma Crichton-Miller

November 25, 2025

Enter the halls of Design Miami and you will find tables built from organic matter and building detritus, dancing on ill-matched legs; a chair that looks like a giant ant; a series of ceramic tables like upside down mountains and a multicoloured shelving unit constructed from melted carpet. This has always been the fair where design explores its wildest edges. But today perhaps more than ever, it seems there is a growing public for these fantasies.

The fair was founded in 2005 by Craig Robins, the Miami-based entrepreneur, real estate developer and collector of art and design. At the time, a few iconic pieces of what was called “Design Art”, a genre of contemporary sculptural furniture, were beginning to fetch high prices at auction — Zaha Hadid’s tables curved like sand dunes, Marc Newson’s aerospace-inspired 1988 Lockheed Lounge chair, Ron Arad’s playful punk pieces created from salvage. But it was still a wayward niche within contemporary design. The sector needed an ambitious platform to open collectors’ eyes to a startling array of experimental pieces that used function merely as a starting point, their true purpose being the expression of desires, the realisation of fictions, the telling of tales. As Zesty Meyers, co-principal of New York’s R & Company gallery, puts it: “It’s making dreams come true.”

Two decades later, the market in these fantastical creations is booming. Twentieth-century trailblazers — from Italian Memphis Group founder Ettore Sottsass and his younger compatriots Andrea Branzi and Gaetano Pesce, to Newson and the Brazilian Campana brothers — have become classics. Meanwhile, younger generations of designers are taking their discipline further into the realms of sculpture, installation and even film, identifying in the craft of building furniture a potent means of creating a world. After all, collectors live intimately with these pieces, handling them, absorbing whatever wild ideas they express as much through the body as through the eyes and the mind. For Meyers, these objects express a basic human freedom: “It’s realising we can live the way we want.”

“I was attracted to this medium because of its accessibility. Design has to be democratic. Humour is key Designer” — Chris Wolston

Museums have taken note. This year in November alone Dallas Contemporary opened Chris Wolston’s first museum exhibition, Profile in Ecstasy, staging his emphatically crafted rattan, clay, aluminium and bronze pieces on four catwalks, animated by music and light devised by his husband, filmmaker David Sierra, leading up to a luminous fountain sculpted in the form of Grace Jones. Meanwhile, Michigan’s Cranbrook Art Museum launched a touring mid-career survey of the LA-based Haas brothers, known for their whimsical sculptures, titled Uncanny Valley.

With his thematic title for this year’s Miami edition, Make. Believe., design scholar and curator Glenn Adamson suggests that key to the flowering of this design avant garde is its dual emphases on “craft and conviction”. For Adamson, the storytelling and the exuberant expressivity emerge from a searching exploration of materials and processes. Within the fair, Adamson showcases a cluster of designers — from Jack Craig, he of the melted carpet, to the enigmatic Dubai-based design brand Kameh — who display what he calls “a transformative energy”, capable of bringing alternative realities into being.

As a counterweight to global doom, he points to Wolston’s joyful creations, emerging from his studios in New York and Medellín, as “perfect examples of how a queer person from Brooklyn can make possible these more positive narratives”. For Wolston himself, the fact that these are pieces of design rather than works of art is critical: “I was attracted to this medium because of its accessibility. Design has to be democratic. Humour is key. Beyond that, artists have to make whatever interests them, and if they stay true to that, they make a world of their own.”

Wolston will offer new work at Design Miami through The Future Perfect. Vikram Goyal, a Delhi-based designer represented by the same gallery, also places storytelling at the centre of his recent work, The Soul Garden — presented at Design Miami Paris earlier this year — a series of beautifully imagined bronze cast mythical animals that provide seating and tables. An avid reader as a child, spellbound by Indian fables, with their intertwining of animal, human and divine kingdoms, he says he “wanted to do something multi-layered. People are looking for fresh narratives and for alternative explorations of spirituality.”

David Alhadeff, founder of The Future Perfect, comments: “Fantastical design invites a kind of wonder back into daily life. It’s tactile, human, even a little rebellious. It allows people to build environments that reflect their inner worlds, not just their Pinterest boards. I think what draws so many makers too is the challenge of embedding narrative and imagination into the everyday. For collectors, it’s the thrill of living inside a story.”

Marc Benda of New York gallery Friedman Benda, a Design Miami mainstay, suggests that throughout history designers have told stories: “It is the attention that has grown. We have learned to look and listen to what an artist is expressing.” He also notes that the public has become more knowledgeable about what making entails, with greater curiosity about materials and processes, and with a greater appreciation of how materials themselves carry stories. In an era where AI is taking over so many areas of life, “the experience of seeing something in real life has become increasingly important” and the lure of explicitly crafted furniture ever stronger.

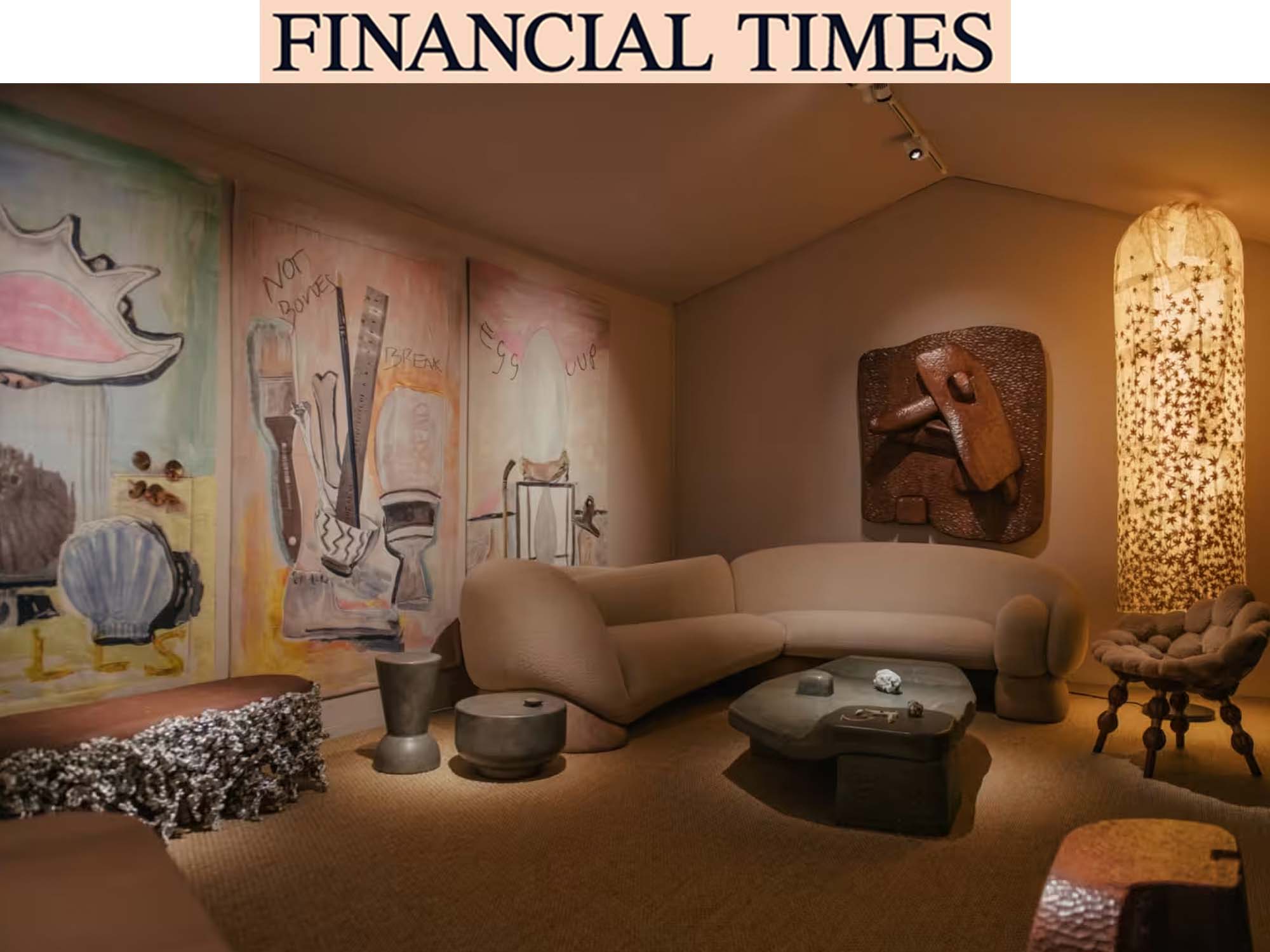

For PAD London, his gallery staged British designer Faye Toogood’s curated booth, The Magpie’s Nest, to reflect her collector’s eye. It offered a whimsical, welcome cocoon against the outside world, with characterful pieces by a variety of designers vying in the conversation with her own. Toogood’s tactile “Maquette 208 / Paper Chair” (2020), made of cast aluminium and acrylic paint, from her Assemblage 6 series of experimental models made with studio debris, won the Contemporary Design Prize at the fair.

An earlier prize winner, Design Miami/ Designer of the Future 2009 Nacho Carbonell, whose hand-built sculptural lights, chairs and cabinets, made from organic materials and debris, evoke the rural Spanish landscape of his childhood, has turned his imagination this year to a new table. His gallerist, Loic Le Gaillard, of Carpenters Workshop Gallery, says about these extraordinary creations, “We are not interested in function. No one needs another chair, another table. There has got to be a story.”

Design Miami, December 2-7, designmiami.com