By Jude Webber

When one of Javier Senosiain’s daughters was in kindergarten, she was asked to draw her house. Her picture showed an undulating green roof and semi-buried structure. She left out the giant shark’s head overlooking the garden but even so, the teacher was alarmed enough to call her mother and the school psychologist. The explanation turned out to be simple: her dad’s an architect.

And not just any architect. Senosiain, 73, is Mexico’s leading proponent of so-called “organic architecture”, a concept popularised in the US in the early 20th century by Frank Lloyd Wright, who sought to place his buildings in a harmonious balance with their natural habitat.

The Casa Orgánica (Organic House), drawn by Senosiain’s daughter, is not just any house either. Built in a residential neighbourhood in Naucalpan de Juárez just north-west of Mexico City and finished in 1984, it is Bilbo Baggins’ Hobbit hole, crossed with the Teletubbies’ Tubbytronic Superdome, meets the modular bubbles of the children’s book Barbapapa. The contrast with the elegant, entirely rectilinear homes all around it could not be sharper.

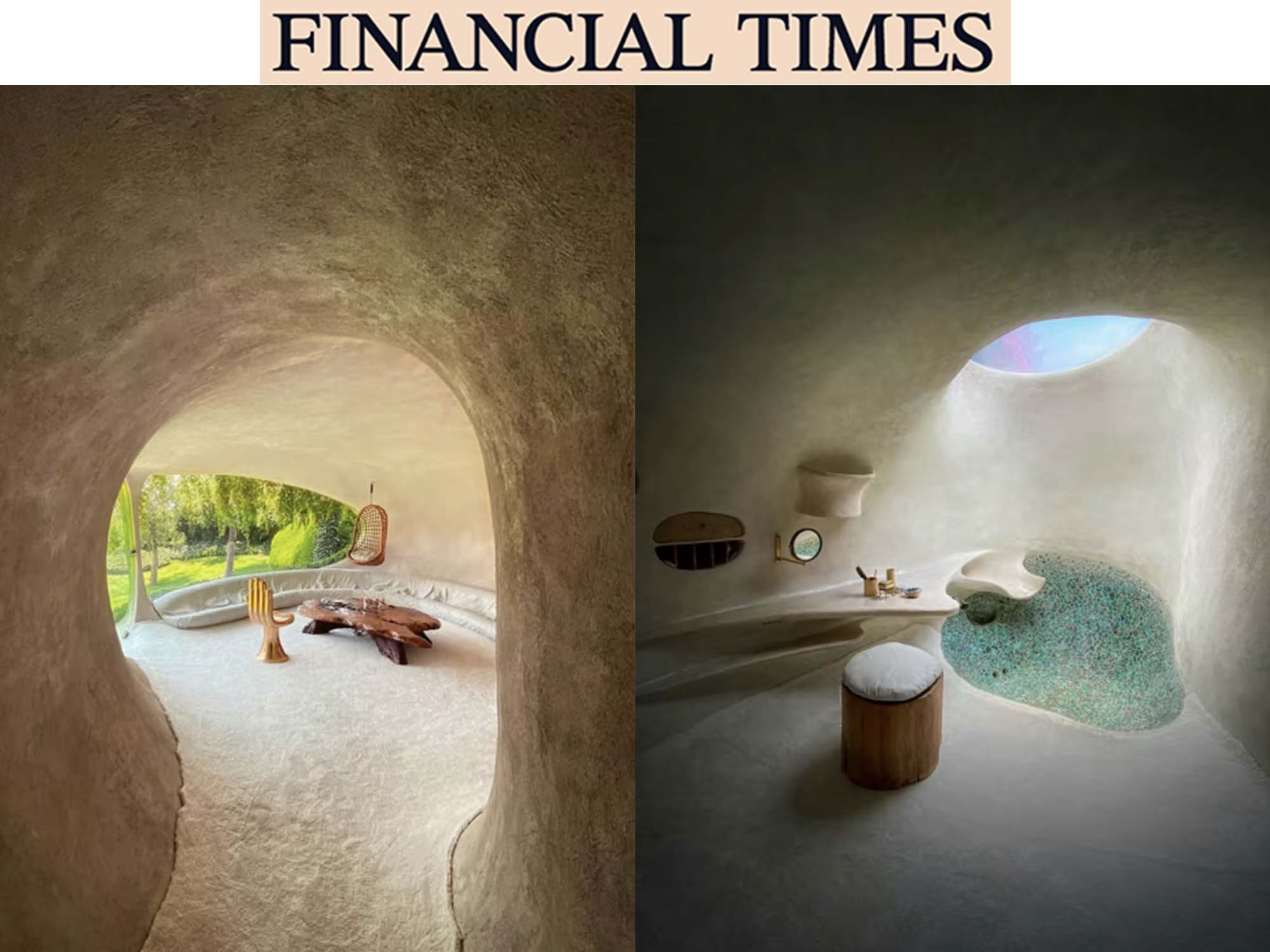

Inspired by caves and igloos, the Casa Orgánica’s tunnels and curves are not only inkeeping with nature but a joyful return to life’s origins. Senosiain sees it as thearchitectural equivalent of a mother’s embrace, or apapacho, a word borrowed fromthe Aztec language, Nahuatl, meaning “shelter of the soul”.

“There are hardly any straight lines in nature,” says Senosiain, who lived in the house for a quarter of a century until his two daughters, now in their thirties, wentto university. “Our natural space is curved, it’s the antithesis of the boxes we’re usedto.”

He embraced swirls and flow to such an extent that he declared early in his career hewould never build straight lines. In fact, he did, but soon threw himself into a gloriousevocation of the natural world’s forms, functions and colours. “I’m even moreconvinced now, with the pandemic, that we’re going to turn to . . . the origin, what isprimitive,” he says on a video call from his Mexico City home, where he is spendingthe pandemic completing a book.

Next to the Casa Orgánica is the Ballena Mexicana (Mexican whale, completed in 1992) covered in vibrant mosaics. Nautilus (2007), another of his most recognizable works, is reminiscent of a conch shell. The Nido de Quetzalcóatl (Quetzalcóatl’s Nest, 2007) is a horizontal apartment block in the shaper of a snake’s body – a nod to the pre-Hispanic plumed serpent deity.

Sam Cochran, features director at Architectural Digest magazine, calls his structures “wildly creative”.

“Senosiain’s work anticipated the interest in biomorphic forms and the innovative merging of indoor and outdoor space that are top-of-mind for many of today’s leading designers,” he says. “It synthesizes many influences into a totally singular point of view.”

To appreciate that in all its glory, you have to take a trip to Naucalpan, a gritty industrial suburb on the northwestern fringe of Mexico City.

The colourful Torres de Satélite (Satellite Towers), designed by famed Mexican arcthiect Luis Barragán and sculptor Mattias Goeritz, rise up from the Periférico ring road..