By Lewis Wallace

HE ENVISIONED UNDERGROUND cities, floating buildings and an eternal space tomb for Albert Einstein worthy of the great physicist’s expansive intellect. With such grand designs, perhaps it’s not too surprising that the late Lebbeus Woods, one of the most influential conceptual architects ever to walk the earth, had only one of his wildly imaginative designs become a permanent structure.

Instead of working with construction and engineering firms, Woods dreamed up provocative creations that weren’t bound by the rules of society or even nature, according to Joseph Becker and Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, co-curators of a new exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art titled Lebbeus Woods, Architect.

“It was almost a badge of honor to never have anything built, because you were not a victim of the client,” Becker told Wired during a preview of the fascinating show, which opens Saturday and runs through June 2. While not a full retrospective of Woods’ career, the exhibit shows off three decades of his work in the form of drawings, paintings, models and sketchbooks filled with bold ideas, raw concepts and cryptic inscriptions. (See several examples of Woods’ work in the gallery above.)

As the curators discussed Woods’ work and his impact on the world of architecture, they talked of a brilliant mind consumed with disruption, with confronting the boring, repetitive spaces humans have become accustomed to living in by challenging the “omnipresence of the Cartesian grid.” Woods’ fantastic visions included buildings designed for seismic hot zones that might move in response to earthquakes, or a sprawling city that would exist underneath a divided Berlin, providing a sort of subterranean salon where individuals from the East and West might mingle, free from the conflicting ideologies of their governments.

“He was very focused, I think, in all of his work, in what he said was ‘architecture for its own sake,'” Becker said. “Not architecture for clients, not architecture that is diluted, and not architecture that really had to be held up against certain primary factors, including gravity or government.”

Woods found his place in the conceptual architecture movement that sprang from the 1960s and ’70s, when firms like Superstudio and Archigram presented a radical peek into a possible — if improbable — future. Casting a skeptical eye on the way humans lived in cities, these conceptual architects were more interested in raising questions than in crafting blueprints for buildings that would actually be built of concrete, steel and glass.

In fact, only one of the nearly 200 fascinating drawings and other works on display in Lebbeus Woods, Architect was ever meant to be built, said Dunlop Fletcher. Instead of the archetypical architect’s detailed plans and models, carefully calibrated to produce a road map to a finished structure, Woods’ drawings are whimsical and thought-provoking, with radical new ideas being the intended result of his efforts. “No project is fully designed,” she said. “This is intentional – Woods allows the viewer to complete the project in his or her mind.”

Woods’ ideas started in his sketchbooks, which he crammed with detailed drawings. “He was extremely gifted with the pen,” said Becker, adding that many of the pieces are notated in a strange hybrid language that could be part Latin, part invented. The curators likened it to a kind of code that connected the conceptual fragments that run through Woods’ highly theoretical work.

“It could mean something, it could be that he’s creating almost these fictional artifacts of these supporting elements to engage with the larger drawings that he would do later,” Becker said. “They’re almost Da Vinci-like in their illegibility.”

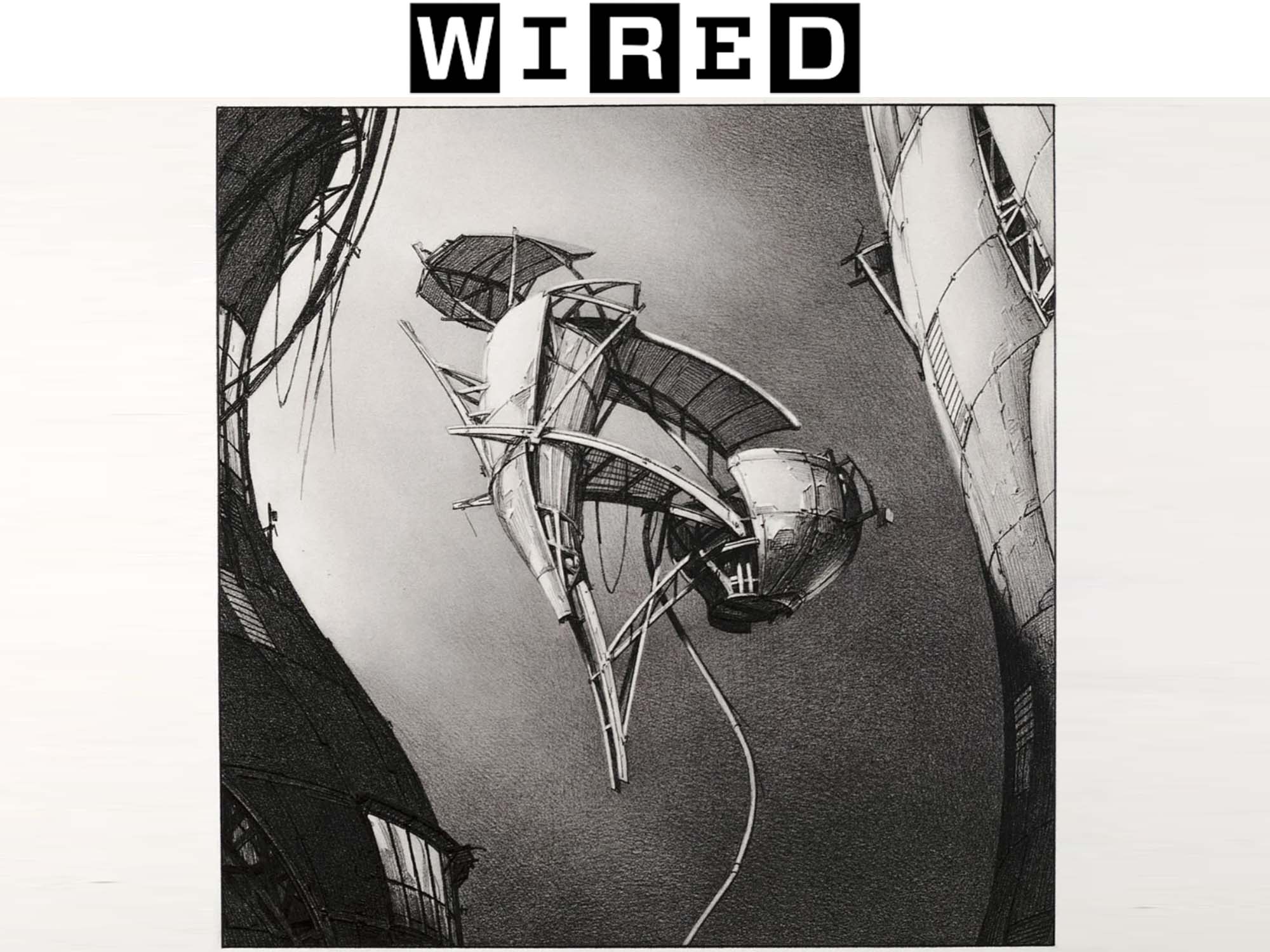

Other questions remain about just what, exactly, Woods was up to with when he took pencil to paper. Take, for instance, a piece called Aero-Livinglab, from his Centricity series from the late 1980s, in which the architect was “essentially creating a utopian city” with “its own set of rules,” according to Becker. The drawing depicts a floating room that resembles an insect as much as it does some sort of alien zeppelin. Just what would the purpose of such a construction be?

“It could be an inhabitable space,” Becker said. “It could be small, it could be large. Often these things don’t have clear scale, but we do know that the point of Centricity was to invite a question of ‘what if?'”

An obituary on the Architectural Record website dubbed Woods “the last of the great paper architects” and said he “achieved cult-idol status among architects for his post-apocalyptic landscapes of dense lines and plunging perspectives. Deconstructivist in the most literal of ways, they were never formalist exercises. Instead, they conveyed the architect’s deep reservations as to the nature of contemporary society, and particularly its penchant for violence. He eschewed practice, claiming an interest in architectural ideas rather than the quotidian challenges of commercial building.”

If It Looks Like Sci-Fi …

With a body of work filled with flying structures, space beacons and bizarre post-apocalyptic buildings that look as if an alien mothership had crashed into them, it’s only natural that Woods’ work drew comparisons to science fiction. Woods designed a set for Alien 3, drawing comparisons to Swiss surrealist artist H.R. Giger, but the whole thing got scrapped when directors changed on the production, Becker said.

One of Woods’ drawings — Neomechanical Tower (Upper) Chamber, which depicts an elevated chair in a creepy, decaying industrial environment — found its way into Terry Gilliam’s 1995 sci-fi movie, 12 Monkeys. Woods filed a lawsuit claiming an interrogation room seen on-screen was an unauthorized reproduction of his work, and won a six-figure settlement. “Essentially, they just ripped this drawing off,” Becker said.

Still, Woods, who founded the Research Institute for Experimental Architecture in 1988 and taught for many years at Manhattan’s revered arts institution Cooper Union, did not see himself as a sci-fi concept artist, according to Dunlop Fletcher, who said the master draftsman’s works “come from a place of really understanding the current built environment, as opposed to a complete fantasy. He seemed to be very hesitant to be kind of thrown into that realm of fantasy architecture.”

Woods said as much when he spoke with The New York Times in 2008. “I’m not interested in living in a fantasy world,” he said. “All my work is still meant to evoke real architectural spaces. But what interests me is what the world would be like if we were free of conventional limits. Maybe I can show what could happen if we lived by a different set of rules.

A New Mission After an Untimely Death

The exhibit was not supposed to cover so much territory. Becker and Dunlop Fletcher had been collaborating with the architect for months, meeting in his Lower Manhattan studio to discuss his work and planning to include a new installation in the exhibit. When the 72-year-old Woods died unexpectedly in his sleep as Hurricane Sandy swamped New York City on Oct. 30, the news came as a shock to the curators.

“It was actually very kind of eerie and bizarre, because a lot of his work deals with ideas of chaos and, you know, even climactic events or geological events,” Becker said. “And for him to pass away the night that superstorm Sandy hit New York, it was almost like it had to be that way.”

After Woods’ death, the curators decided to expand the exhibit to include more pieces from throughout the late architect’s career. Both were drawn to one of his earliest works, the Einstein Tomb project, done for Steven Holl and William Stout’s Pamphlet Architecture series. Woods proposed a kinetic space tombstone for the great thinker, whose cremated remains had been scattered in the Atlantic Ocean.

“Lebbeus imagined a more fitting tribute to the mind of the man,” Becker said, “and so designed this monument — this cross-shaped monument with these different elements that would actually travel on a beam of light into the universe and perhaps back, and perhaps out and back again forever, dealing with issues of relativity in the monument itself.”

The project’s presentation in Lebbeus Woods, Architect is typical of the SFMOMA show: Multiple drawings showcase the progression of Woods’ idea in bold black and white, while an aluminum model shows what the timeless memorial might have looked like had it actually been built.

And speaking of things actually being built, what about that structure in China, the only example of Woods’ work ever to be constructed? Neither Becker nor Dunlop Fletcher have seen it, but they described it vividly. The Light Pavilion is embedded within a massive building designed by Woods’ collaborator and friend, Stephen Holl. Glass walkways and stairs allow the visitor to stroll through the gigantic plastic shafts and metal rods that comprise the structure, while the sides, ground and ceiling are covered in mirrored material.

“It just really feels like this expansive space,” Becker said.

While both of the curators said they would love to see Light Pavilion, which Woods designed with his colleague Christoph A. Kumpusch, Becker then expressed the slightest of reservations, based entirely upon his respect for a life’s work that leaped from a deep mind to the printed page but – aside from audacious art installations like The Storm and The Fall – never before into the “real” world.

“Being that the entire career of this guy was based in the unbuilt,” Becker said, “I’m afraid of going there, you know, because it could be that he had to give over a lot of his control to somebody else to build it…. So I’m a little wary.”