By Andrew Gardner

Call it sloppy, weird, retro, kitsch, maybe even ugly. What it isn’t: symmetrical, refined, or uniform. Young and established artists and designers alike, working across a variety of media, are finding their voice in the beauty of the imperfect, carving or hacking their materials, or casting objects in unconventional media.

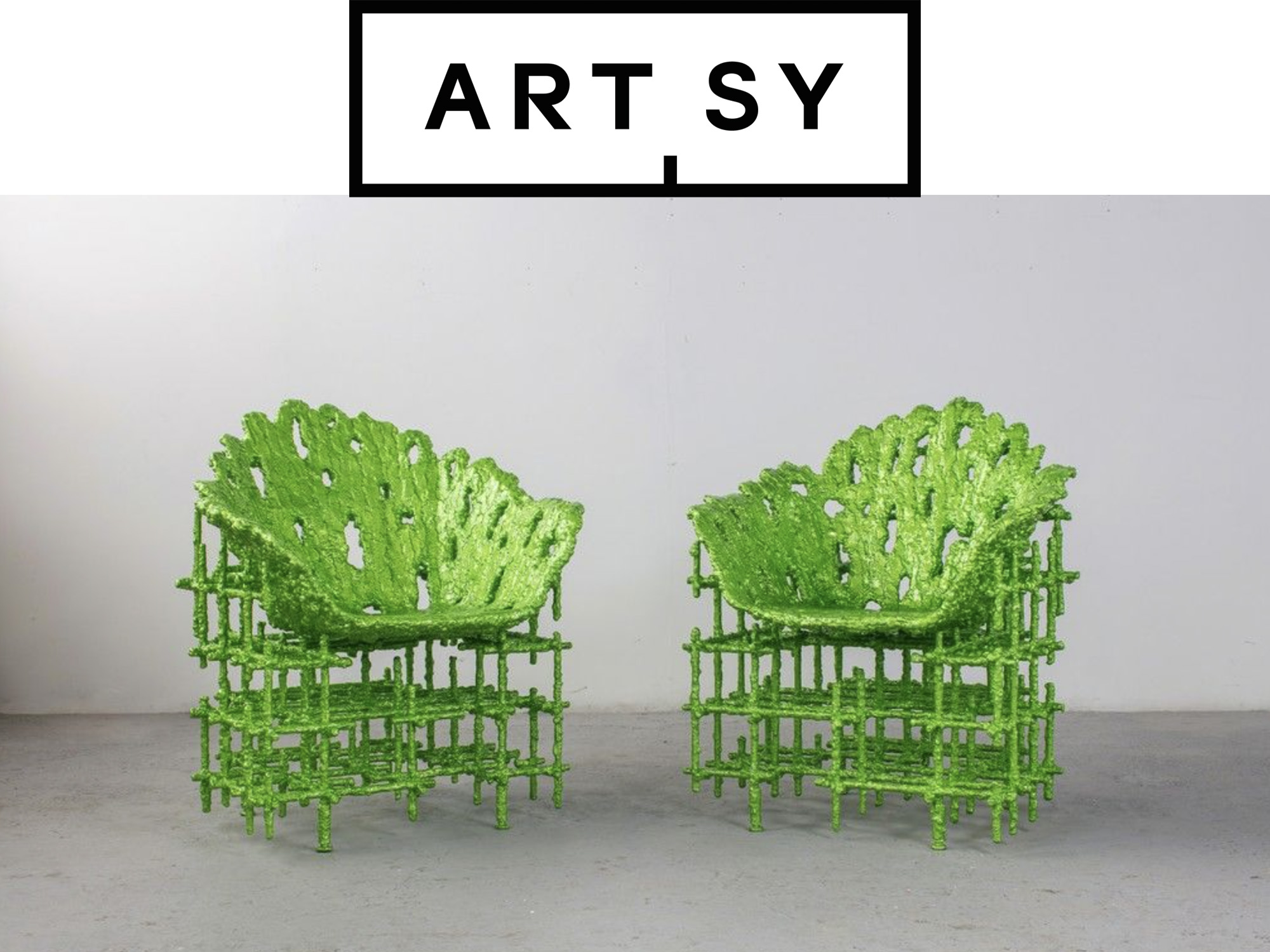

You can see it in New York-based designer Katie Stout’s irreverent, girlish vanity mirrors and floppy hat rugs; in Brooklyn-based Misha Kahn’s engorged, sculptural tables and chairs; and in Detroit artist Chris Schanck’s wonderfully textured cast furniture. Or take American designer Liz Collins, who experiments with bold colors, energetic zigzags, and hanging warps in her textiles—woven forms that artfully straddle the line between order and chaos.

Meanwhile, ceramicists like Jennie Jieun Lee and Gareth Mason create deconstructed vessels decorated with strange and exciting painterly glazes, while the Swedish-Chilean designer Anton Alvarez, primarily known for his thread-wrapped furniture forms, experiments with extruded clay pieces that verge on delightfully grotesque.

Even the field of graphic design has seen a renaissance of glitchy, Web 1.0 aesthetics, as chronicled by Zürich-based art director Pascal Deville on brutalistwebsites.com; while in fashion, the “aggressively unglamorous” looks (as Marc Bain aptly described it on Quartz) parading down the runways of established (Prada, Balenciaga) and emerging (Vetements, Eckhaus Latta) brands are the talk of the fashion blogosphere.

Whatever you want to call it, design that is deliberately upending traditional notions of beauty is having a moment.

Jonas Nyffenegger and Sebastien Mathys, the Swiss founders of @uglydesign, a popular Instagram account, have been drawn to documenting the weird and the downright ugly in the world of design for the last four years. Their success (the account has over 60,000 followers at the time of writing) suggests a broader attraction to objects and forms that bend the conventional rules of taste.

“I consider ugly as beautiful,” Mathys says. “I would cry if there weren’t any ugly designers anymore, if all our surrounding objects and items looked the same.”

As design critic Stephen Bayley, author of Ugly: The Aesthetics of Everything, wrote in a 2013 essay for The Architectural Review: “The strange truth is: too much beauty would be intolerable, an awful world of meticulously cropped lawns and starched linen.”

Perhaps somewhere on the road to the slick perfection of Apple designs, everyone got a little bit bored. The Dieter Rams-influenced aesthetic of Jony Ive’s iPhone has reached full-blown mainstream, where minimalist interiors (promoted by tidying guru Marie Kondo) and mid-century modernism (popularized by stores like Design Within Reach) have permeated every aspect of the way the cosmopolitan and urbane live their lives in the 21st century.

Now, a newfound embrace of the wacky and weird has come in the form of a resurgent interest in the bright colors and bold patterning of the 1980s design collective Memphis (led by the Italian architect and designer Ettore Sottsass)—and in a full-fledged embrace of craft media like ceramics and textiles.

“The digital age has made everyone want to get their hands into things and get dirty and messy and make things out of clay,” says Collins, who has taught at art schools around the country. “With that comes the voice of the hand, which is inherently imperfect.”

For French-born, London-based Marlène Huissoud, who makes wild furniture from bee resin, an embrace of imperfection also means submitting to the idiosyncrasies of your materials rather than imposing too much order on them. “I don’t use computer software as I like to be as free as possible in the making process,” says Huissoud. “Nothing has to be determined for me when I start creating.”

And while art schools once focused on honing a specific craft technique or media, “sloppy craft,” as scholars like Glenn Adamson and Elissa Auther have called it, has garnered newfound cultural currency, where concept and form don’t necessarily have to go hand-in-hand.

The origins of “sloppy” design

There are antecedents to this current taste for the weird. Just look to the interest in studio craft in the post-World War II Western world, rooted in the idea that hand-crafted, material-focused work was infinitely more interesting and desirable than the machine-made uniformity of Bauhaus modernism.

In this period, American designer George Nakashima’s furniture celebrated the raw edge of a wooden plank, whileceramicist Peter Voulkos played with thrown clay vessels that were summarily dismantled and hacked into to become the basis for his sculptures. Fiber artists like Sheila Hicks, Josep Grau-Garriga, and Magdalena Abakanowicz embraced the materiality of their media with an intentionally hand-rendered appearance.

Meanwhile, a coterie of radical designers working in 1960s and ’70s Italy rose to the fore. They were “absolutely concerned with upending the ideas of universal design and good taste that had such a powerful stronghold on the design community since the turn of the 20th century,” according to Shelley Selim, Associate Curator of Design and Decorative Arts at the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

“It was about favoring expression over function, the sensual over the rational, and multivalence over universality,” she says.

The Memphis design movement grew out of this shift in tastes, as did the careers of American architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, whose postmodernist aesthetics embraced humor and kitsch by reinventing historical forms (see their divisive Queen Anne chair). As Selim says, “Postmodernism is one of the greatest tributes to ugliness the Western architecture and design world has ever witnessed.”

In the 1990s, Droog, the Amsterdam-based design collective critiqued the waste resulting from newly globalized systems of production by incorporating found and discarded textiles in their aesthetically questionable rag chair, while Dutch designer

Maarten Baas’s clay furniture from 2006 gave hand-crafted, irregular forms greater visibility in the Internet age.

“That same youthful desire to defy the earnestness of modern design or just general homogeneity is present with younger designers today, and that can manifest in so-called ugliness,” says Selim.

An “ugly” aesthetic for our contemporary world

“People want things more unique, customized only for them,” Nyffenegger says. “A world too sober is boring, and a world too eccentric is exhausting. We need both. I think designers are searching for a new aesthetic.”

Finding that “new aesthetic” is a quest that has preoccupied artists for time immemorial. Often, the development of a new vocabulary in art and design is the result of political turmoil and social upheaval. Given the current state of our world—environmental degradation as a result of climate change; civil wars in South Sudan, Syria and Yemen; political division and the rise of far right nationalism in America and Europe—it’s no wonder that artists and designers are seeking a new language.

Chris Schanck, who was trained as a sculptor and later found his way to furniture, sees imperfect design as a direct response to the failure of late-stage capitalism—an effort to “open up the space to imagine new futures and new cultural symbols,” he says. “It’s hard to manufacture cultural objects when capitalism and manufacturing no longer satisfy the needs of a growing class of peoples.”

His humanistic approach extends to the values and principles practiced in his studio, where he has hired workers from across Detroit to help realize his wild aluminum and resin furniture. “The quality of our work is equal to the quality of our relationships,” he says. “Without a mutual respect and shared vision, the work would be impossible to create.”

For Katie Stout, whose brand of so-called “naive pop” calls invokes signs and symbols from everyday life, the embrace of the ugly or imperfect expresses a streak of nihilism. “I think a lot about [the early 20th-century art movement] Dada and how, after the devastation of World War I, nothing made sense so they made nonsensical work,” she says. “I think people are reacting to nationalism and the absurd political climate by making absurdist work.”

Case in point: her barely standing stuffed chair series, which overturn any prevailing concept of what a chair should look like and how it should be used.

The absurd is a central preoccupation for Nyffenegger and Mathys, too, who initially established an “ugly design” Tumblr account after seeing a bathtub redesigned into a sofa at the 2013 edition of the design fair Salone del Mobile in Milan. “We want to see things we could not even dream of. The more absurd the better,” Nyffenegger says. “It’s the opposite of everything we learned in design school, making it even more funny and kind of rebel.”

An embrace of imperfection

“The tides of taste go back and forth, erasing aesthetic certainties,” Bayley wrote. “This is a truth so disturbing that most of our assumptions about art are immediately and ruinously undermined.” This is true of design, too—much of the work that may have once been considered bizarre or distasteful is now considered quite appealing, or even beautiful.

And the art and design worlds are taking notice, with a number of exhibitions and festivals highlighting the work of these innovative design talents. This month, Stout will present a solo show at New York gallery R & Company, while Huissoud brings her latest work to the London Design Festival.

Meanwhile, Collins will be presenting an immersive textile experience at the New Museum as part of a group show that opens September 27th, entitled “Trigger: Gender as a Tool and A Weapon.” And in the coming months, New York design gallery Friedman Benda will present solo exhibitions of the work of Chris Schanck and Misha Kahn.

For Nyffenegger and Mathys, their project documenting the latest and greatest in ugly design will continue, with eyes trained on crimes of aesthetic proportions. In archiving such abuses, they hope, of course, to make people laugh, but they also hope to serve as advocates, highlighting a need for contemporary designers to embrace experimentation and not be afraid to make something a little ugly.

After all, as Bayley wryly observes, “If everything were beautiful…nothing would be.”