By Ella Martin-Gachot

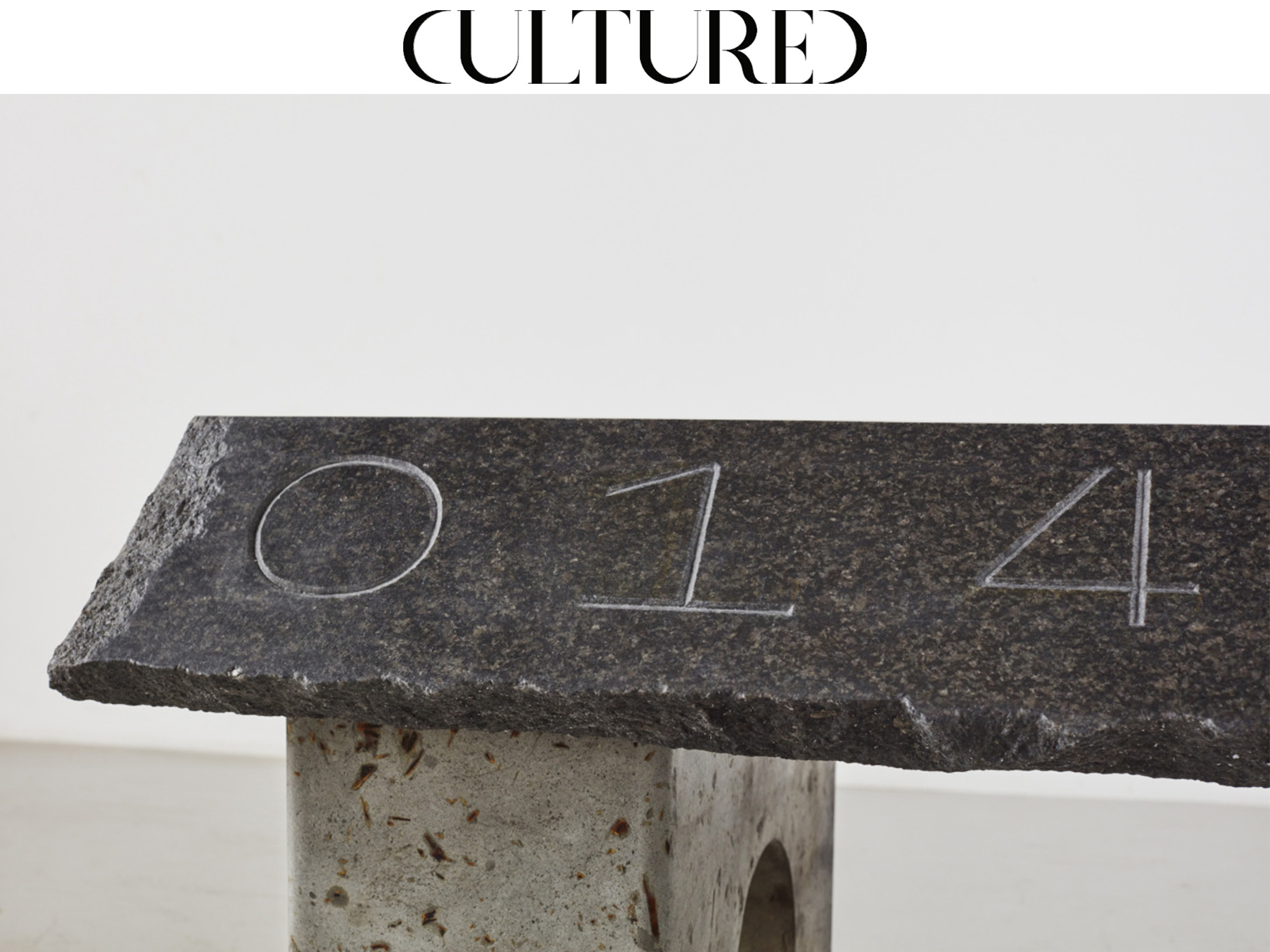

“COARSE,” the British creative’s first show in New York, opens tonight at Friedman Benda. Through materials ranging from Abidjan clay to turmeric, the exhibition explores diasporic geographies, regionalized aesthetics, and the true purpose of furniture.

Later this month, Samuel Ross will turn 32. At this age, the British designer and creative director has achieved a level of industry-spanning achievements that is, quite frankly, overwhelming. After studies in graphic design and illustration, and stints in advertising and product design, the creative was scouted by Virgil Abloh, working on a plethora of the late designer’s collaborative projects. In 2014, he founded A-COLD-WALL*, a deeply intellectual and critical luxury menswear line. Five years later, he opened SR_A, a design studio that’s worked with giants like Nike and Apple.

In 2020, he launched the Black British Artist Grants; last year’s recipients include Rhea Dillon, Torishéju Dumi, and Jebi Labembika. Ross also has an abstract painting practice, on view at White Cube Bermondsey in “Samuel Ross: Land” until May 14. And tonight, he makes his New York gallery debut with “COARSE,” where he presents a body of work that mines materials as distinct as Abidjan clay and turmeric to create playful composite objects that probe geographies, aesthetics, and the purpose of furniture. To mark the show’s opening at Friedman Benda, CULTURED chatted with Ross about artistic DNA, developing a signature, and the language of servitude embedded in design.

CULTURED: Tell me about the ethos of “COARSE.”

Samuel Ross: This showing of artworks [has] the confidence and willingness to really push the transformation of raw material into a new remit, which is of course laced with historical and geographical influences and observations on race and politics. I love the idea of furniture and design having this language of servitude.

CULTURED: These questions of servitude, and who gets to sit on what and how, are so interesting, especially when placed in the setting of a white cube gallery.

Ross: There’s something really exciting about how you play with pragmatism and the expectation of what furniture and objects fundamentally need to achieve, and how that engagement becomes a performance in itself. To a degree, there’s something there with shaping the body, which you can compare to the work I do with fashion.

To serve well, you must be truthful. It sounds a bit spiritual, but that is a huge part of the work. Truth comes in well-made functional materials being put together, and it also comes through the signaling and the messaging of what all the materials or color or form or position of the body mean.

CULTURED: I’d love to backtrack a bit and understand how you arrived at industrial design.

Ross: I am fortunate to come from an academic and creative household. The genome just replicates itself, right? What I deem to be my identity is actually my father’s identity and his mother’s identity. Having a throughline in the arts is like physical material being passed down. It’s just a different incantation of the same composite of DNA. It’s almost as though this is not really my choice or doing.

CULTURED: Which is both liberating and terrifying…

Ross: It really is, because then it goes into old world perspectives on essence, and the humors, and nature versus nurture. It ties into EQ, IQ, class, and opportunity. There seems to be something so innate about my identity. I look through images of my father, and I see him painting and having sculptures placed on his face. He did fine art at Central Saint Martins; my mother is now a painter. So anything that I’m doing, it’s what I know to be a way of mediating the world, and I think that kind of starts in the household, right?

The idea of art and commerce is ingrained in my first memory of sculpting as a child in nursery at age 3. And my second memory would be selling a picture at an after-school club at age 7. My first memory of design would probably be going to my father’s open day for his MA course in glass technology when I was around 12 years old. This idea of there being a separation between a practice and a life has never really been in place for me.

CULTURED: Could you speak to your relationship to Brutalist aesthetics, which are so present in your work?

Ross: If you think about British-Caribbean and Caribbean diasporic aesthetics, interiors, and materiality, it’s actually almost neo-Baroque—dark mahogany, gold leaf foiling, doilies. That aesthetic is all I recognized for a large part of my formative years as a child. There’s also this relationship between the “mother country,” which is how my elders would speak about England, and a reverence for imperial design. But I knew it wasn’t me.

Before I knew it was Brutalism or Postmodernism, I encountered these architectural movements where my friends lived in working class estates within the U.K. I felt very familiar with the materials. When I think of [design elements like] Portland cement with grouting, I think of friends I grew up with and experiences I had with those people.

The reason it’s so prominent in my work is not just the emotional and lived connection, but understanding the psyche of the architects and designers. And how egregious some of the failures of this movement were. There’s something quite powerful about this notion of failure becoming a symbol for visibility.

CULTURED: What are you injecting into the works on display in “COARSE” that’s new and different for you?

Ross: The integration of historic West African forms was a real focus prior. My thinking has expanded now. Being of the African diaspora, any form I make is African. That has given me an autonomy and a malleability to actually advance the forms that we previously recognized as being from that region. There’s almost a neo-prehistoric form to how the works are shaped and how materials are treated. I’m pushing the notion of a linear timeline aside and saying, “What happens if we integrate the experiences of the texts I’m ingesting with projections of the future and experiences of them now?”

I’m just looking at everything as a composite. There isn’t really a difference between honey and sandstone as materials. This integration of humans wanting to project who they are through physical material and trying to dissolve the difference between the body and the material is something I’m trying to convey by mixing in food materials to bridge the gap. I’m trying to remove a hierarchy of materials, even though they’re sourced and pulled from different locations.

I’m interested in talking about the human experience, from foodstuffs, down to geography, down to synthetic materials. That’s the introduction of, let’s say, Portland cement concrete and a turmeric dye with decimated plywood, integrated into a single composite or single material. It’s almost about developing IP within this space. That’s really important: what is my signature?

CULTURED: How do you see yourself as an artist and designer?

Ross: As a mediator and a conduit for the public discourse of our times. If a young Black man is strangled to death, that’s in the viewfinder. If it happened, it needs to be documented, and historically that’s the job of the artist: to protect the lineage of subtext that our future generations will inherit and to use that documentation or premonition to steer humanity in the right direction.