By Caroline Roux

In January 2019, on a cold winter’s day in London, Samuel Ross reached a pivotal point in the presentation of his fashion collections. The young UK designer was already known for chilling room temperatures down to freezing and playing eerie acoustic harmonies before sending models down the runway in clothing that hovered between streetwear and industrial workwear, often in uncompromising fabrics. This time, the looks were minimal and chic—a belted silvery trench coat, a quilted brilliant-orange gilet—while dancers floundered in pools of dark water and Rottweilers barked. “It’s been a process of implosion and explosion,” says Ross from his studio in central London, “excitement and experimentation.”

In a short time and though only age 29, Ross has gone through an arc of development that would take most people decades. From studying graphic followed by product design to creating conceptual and then wearable fashion, he launched his label, A-Cold-Wall, in his bedroom in 2015, with a 2,000-word dissertation. “It was a think piece,” he says. “I wanted to communicate something intellectual and critical, to identify what needed to be said and then turn it into clothing.”

“It’s been a process of implosion and explosion, excitement and experimentation”

— Samuel Ross

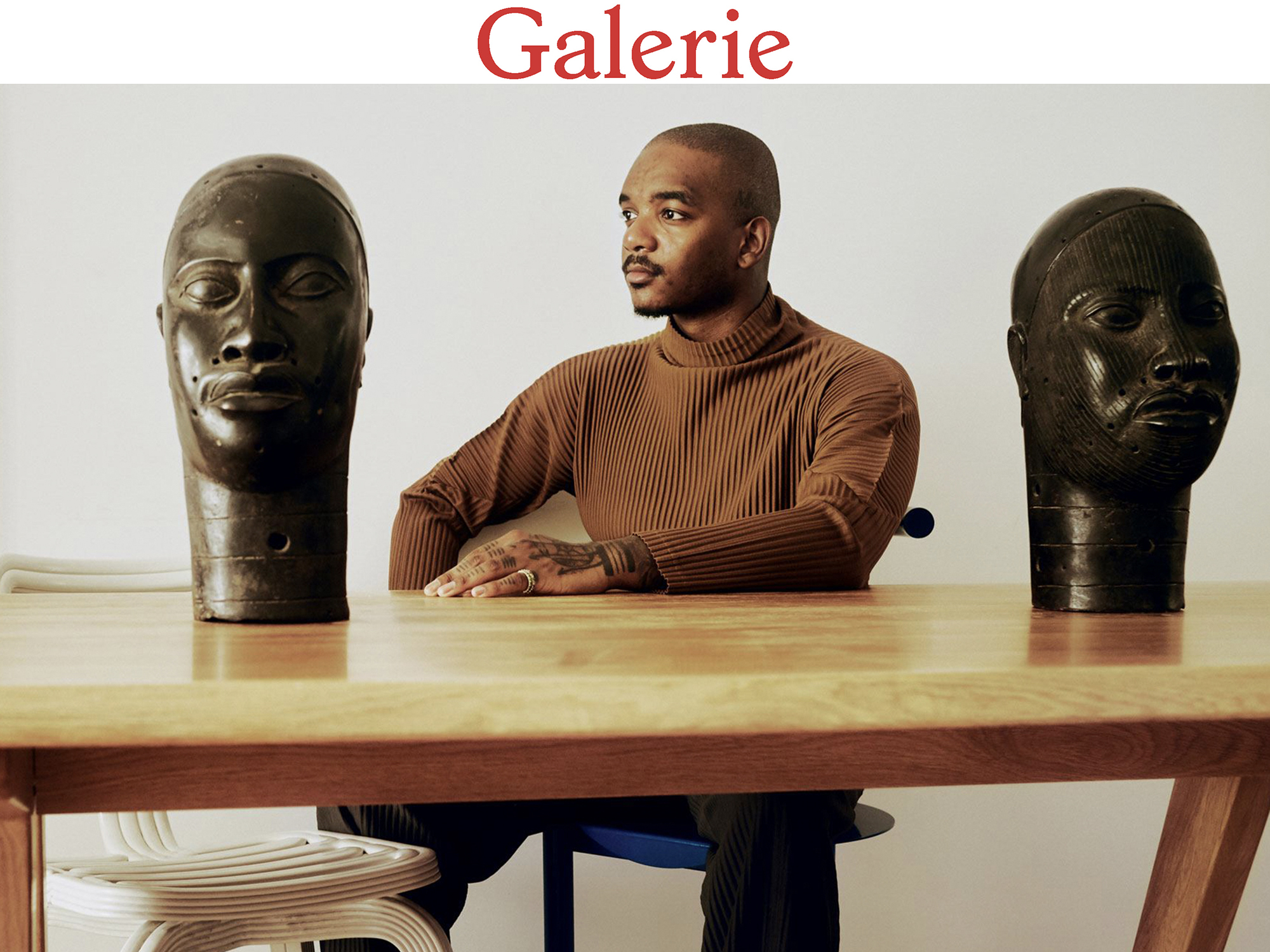

Ross’s latest runway show—a digital presentation in January 2021—was a slick affair. And now he has also added sculptural pieces to his repertoire. A trio of chairs, developed from deep narratives around three centuries of the Black experience, will go on display at the New York design gallery Friedman Benda this spring. Recovery Chair, Signal-3, and Trauma Chair have a granular texture that Ross describes as “raw and exposed.” The extended form of the Recovery piece has been finished with an organic wax “to give it freshness”; the Signal-3 has a rubberized finish; and the Trauma design is marked with signs of scars and healing, punctured with die-cut holes, then coated in a lacquer that’s been mixed with molasses. Not for the fainthearted, it weighs nearly 200 pounds.

Across his oeuvre, the narrative revolves around the complexities of class, particularly the working one, in contemporary Britain; the significance of industrial jobs in a postindustrial world; and the difficulties inherent in the Black diaspora. Ross himself was born in London to first-generation British Black parents, before moving to the Midlands, one of the last parts of the country where industry shakily lingers. “My background was weird,” he says. “My dad studied fine art at St. Martins, but there was no outlet for him—the social landscape didn’t allow it.”

His mother is a teacher in Northampton. The town (once known for its shoe manufacturing) is 60 miles from London, and it is here that Ross is building a new studio. “That’s going to be the temple of contemplation,” he says. “A real lock-in where I can get right into the work.”

His work ethic is fearsome, not unlike that of his mentor, Virgil Abloh. Ross’s Terminal 1, a dazzling orange structure suspended with netting that addresses the need for shelter, helped him win the 2019 Hublot Design Prize. His clothing is marked by a precision and technicality that are now flowing freely into his art. “There will be more pieces by the end of the year, and I want to show them somewhere major, where as many people as possible get to experience them,” says Marc Benda of working with Ross, whom he met through Daniel Arsham. “This is just the beginning.”

A version of this article first appeared in print in our 2021 Spring Issue under the headline “Pivot Point.”