By Sophie Lee

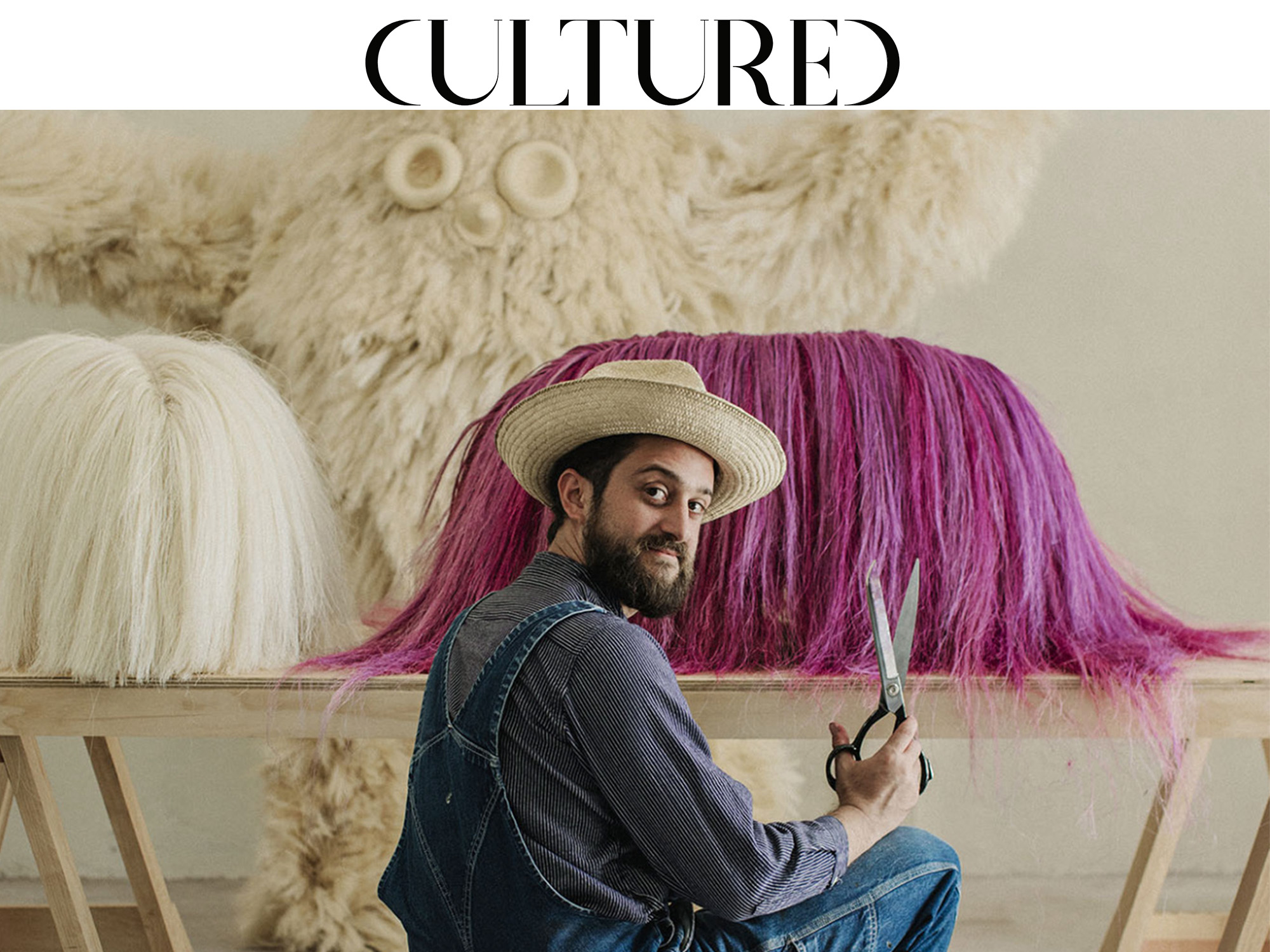

Fernando Laposse has been working with Puebla locals since 2015 to build pieces that are a testament to their enduring culture and environment.

For Fernando Laposse, the process of making art begins with the land. Since 2015, the Mexican-born designer has collaborated with native people in the Puebla region of Mexico to create objects from overlooked plant fibers and ancient natural materials. The fruits of this ongoing project are on view in his latest exhibition, “Ghost of Our Towns,” at Friedman Benda in New York.

The Central Saint Martins-trained designer‘s work aims to counter erosion of both land and local culture; chairs and tables double as art objects and tools for advocacy. In December, four years’ worth of his research will be on display at the NGV Triennial in Melbourne, where the artist is highlighting the dark side of avocados. Here, Laposse offers insight into the origins of his work, how good design can fight deforestation, and why it’s time to rethink the way the discipline is taught.

CULTURED: How did the show with Friedman Benda first come about?

Fernando Laposse: I started working with the gallery about three years ago, but the idea of a solo show came about perhaps in the middle of 2022 when Marc Benda suggested a show that showcased the stories behind my most used materials and the place where they are produced. We landed on the title, “Ghost of Our Towns,” as it speaks of the reality of Tonahuixtla, an Indigenous village trying to keep the fibers of their social fabric from unravelling under the pressures of the modern world we have created. It’s a play of the term “ghost town,” as one of the main issues there has been the mass migration and abandonment of their traditional lifestyle.

CULTURED: Where did your interest in agriculture originate?

Laposse: I visited Tonahuixtla as a child and it became almost like a summer camp growing up. That’s where I learned about traditional farming from a young age, and I suppose that’s where that curiosity for natural materials first originated. My return to Tonahuixtla as an adult and as a designer has been mostly focused on trying to preserve that dying lifestyle and to revert the social and ecologic damage that has been inflicted upon them as a result of globalization.

My agave and corn pieces are done with plants that we harvest and transform into workable materials for furniture making, but it goes beyond that. The corn leaves, for example, are from native corn that was wiped out of the area after the NAFTA agreement in 1994 changed the whole agriculture market and farmers were priced out by industrial GMO corn and the chemicals needed to grow it. The use of these chemicals caused devastating erosion, and in turn migration, as farmers couldn’t grow anything anymore.

So the work that we have done together for the past nine years has been about reintroducing these ancient varieties of corn and reverting the erosion using agave plants that retain soil and water. We finance these projects by creating the pieces of furniture you see in the show, which are made with the corn husks and the hairy fibers from the leaves of our reforested agaves.

CULTURED: What has the response been from the community to your work in their village?

Laposse: At the beginning, it was hard because they were very distrusting, but we slowly built that trust. We started with only two families and now we have more than 30 subscribed to the project. I think the best part is how with each year we have more people planting and going back to their traditional permaculture model, and also to see these heavily eroded mountains get progressively greener as the years go by.

CULTURED: Looking at your work, and projects like the one in Tonahuixtla, where do you think art and design ends and scholarship and activism begins? Are they one and the same, or do you find yourself toggling between each?

Laposse: I see it as something that is completely intertwined. In design school, I was taught that design was about problem solving and I was always bothered by that because, to me, the problems we were learning to solve were a bit made up and it was mostly about how to make something new to sell. You could say I found peace with that preoccupation through activism and problem solving focused on a rural reality.

CULTURED: Having been formally trained in design and worked in the industry for some time now, what do you think is often overlooked in teaching and production?

Laposse: In teaching, I think we need more programs separate from traditional product design. Most courses program young students to perpetuate the cycle of overproduction and consumption. I also think we need to diversify this idea of human-centred design to include people who are not urban and who lead lives that are much more in tune with nature.

After all, despite the fact that most people live in cities now, you still have many that don’t, and many that wish they didn’t. We all need to make money, but we can’t drink or eat money. We therefore need designers that will help solve the questions of how we create more environmental wealth, and for that we need a radical shift to the way we teach this discipline.

CULTURED: What do you hope viewers take away from this show?

Laposse: I hope they leave with a better understanding of the interconnectivity of the world and how these global markets can have such profound consequences in localized communities. But I also want them to leave full of positivity and curiosity about finding a project of their own. Damage can be reversed and it can happen quickly if you put your mind to it.

“Ghost of Our Towns” is on view through October 14, 2023 at Friedman Benda in New York.