By Giovanni Comoglio

We retrace the career of the great designer, theorist and architect through the archives of Domus, where he debuted exactly 50 years go.

“Rockefeller greets us from the 350th floor: ‘Come here, come on darlings, get in, please!’ And there comes Ettore Sottsass, sitting on the hood of a taxi going the wrong way down the Avenue of the Americas, all dressed as a Mexican in pink tulle, and there come the 13 Archizooms in asbestos shoes with magnetized soles, with purple shirts open on the chest on which hangs a small transistor bijoux, and here’s La Pietra in tango-coloured lamé, electric tie, and his all-gold clarinet. (…) Then they all speak into the microphone, about us, about Domus, about Galliano liqueur, about Carnera etc. etc., and they all thank Italy for what it has done and what it is doing for the world. At midnight sharp (…) the spire of the Empire State Building lights up, and the Madonnina appears!”

Exactly 50 years ago, a young Andrea Branzi made his debut on the pages of Domus (Italian Power, Domus 511, June 1972) with what is perhaps the most important document on “Italy: the new domestic Landscape” exhibition at MoMA – after its legendary catalogue, of course: a small editorial column that kicks up a fuss about all the establishment’s rituals, just to join them again the minute after, throwing aphorisms and neon lightning bolts and various kinds of candy. The “spiritual guide”of Archizoom by that time, as Ugo La Pietra defined him, Branzi was at the forefront of that Italian radical design wave that Lapo Binazzi of UFO, again on Domus, would describe as an all-too-bourgeois phenomenon, capable, however, of questioning and highlighting the contradictions of the orthodox-Marxist positions of the late 1960s (Domus 578, January 1978), a wave Branzi wisely rode in order to practice a thorough “technical destruction of culture”.

“Radical architecture is situated within the more general movement of man’s liberation from culture, (…) and tends to reduce all design processes to nought, refusing to play any part in a discipline bent on prefiguring an already coded future through environmental structures.” – Andrea Branzi, 1978

In half a century of Domus, as well as of international history of design, Andrea Branzi has always played the role of a great shaper of questions and a great picker of rational systems, especially of prejudicial or ideologized ones: a “living consciousness of design” – as Alessandro Mendini had defined Enzo Mari, but on a radically opposite front, which in 50 years of evolution would shift through a great variety of shapes.

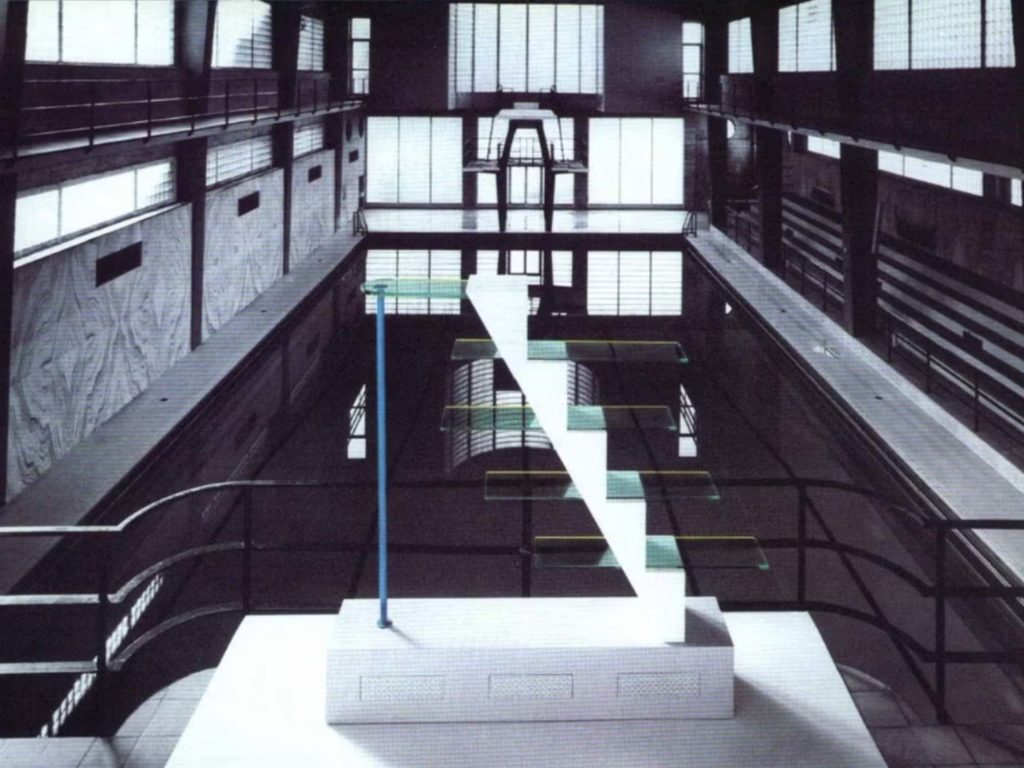

The radical was over before the end of the 1970s, “It’s all over!” La Pietra said, (Architettura Radicale in Italia. Che ne è successo?, Domus 580, March 1978). A year later, Branzi was already working on a way less utopian project, still centered nonetheless on the industrial object as a repeatable and communicative medium: the prefabricated post offices developed by Pierluigi Spadolini for the Italian National Post Service, which now characterize urban and suburban landscapes throughout Italy. In this project Branzi took specifically care of the furniture and the identification systems (In Italia, uffici postali in serie, Domus 594, May 1979).

Design as a medium: two years later, historian and critic Benedetto Gravagnuolo presented on Domus a new collection of furniture pieces created by Branzi, confirming that his production “should be ascribed to visual languages” (I linguaggi ereditati, Domus 619, January 1981), undermining the established hierarchies of scale of interior architecture, but above all “betraying the past for the sake of the present”: Branzi, who was collaborating with Mendini’s Alchimia and was soon to join the Memphis team, may have been announcing himself as a theorist of weak thought and of the object as metaphor, but he had very little of the typically postmodern historicism.

“What is stated is, in other words, a tautology of things. (…) And yet, glimmering between the rigid links in this frozen disenchantment, is the elegant hope of invention. This, perhaps, is why Branzi’s happy objects inspire a sense of mild optimism at the sight of something new at last.” – Benedetto Gravagnuolo, 1981

Branzi is indeed an explorer of timeless primitivisms, as in the raw wood elements that complete his 1985 pieces (Abiti neoprimitivi, Domus 667, December 1985), and a promoter of a strong “presentist” realism, when it comes to identifying a new path of growth for contemporary design, as recounted in the programmatic points of the Domus Academy, of which he has been the educational director since its foundation in 1982: “Design today is no longer a discipline based on an ‘infallible’ design methodology, as it was believed until the 60s; a discipline, that is, so rational that it could solve any kind of problem,” he wrote on Domus 633. “The relationship between man and his objects is rapidly changing” he continues, arguing that “designing today actually means contributing to the design of a new metropolitan life. Today’s city is no longer identified by architecture, but by the market, by the goods that circulate in it”. And he concludes by stating that “designing commodities therefore means (…) designing new urban structures and a new cultural territory”.

Through the 90s, Branzi has increasingly become the prophet (a word that labels him quite frequently on Domus) of a fluidity of thought springing from a “stream of events that ultimately symbolises a computerised Giotto”, as Germano Celant put it in the book dedicated to the Florentine designer (Domus 750, June 1993).

Branzi operates and reflects from the position of a weak thought whose products, even industrial objects, act as a continuous interrogation to the present, like the one staged by the big decorating his Folly 10 at Tsurumi Riokuchi Park in Osaka (Andrea Branzi Folly 10 Osaka, Domus 730 September 1991). The operative method, on the other hand, is firmly anchored to two main outputs: industrial objects, which have flooded the pages of Domus throughout the decade, and texts, essays, reviews, manifesto-editorials. He would take a position on the forthcoming and necessary birth of an Italian Design Museum (Intervista con Andrea Branzi, Domus 792, April 1997), and on several editions of Salone del Mobile (Domus 762, November 1994); he would throw in our faces the condition of Design after God (Il design dopo Dio, Domus 787, November 1996) – that specific design approach which must base on the awareness of a profound humanity of the present, made up also and above all of consumption and commodification – and then by the end of the millennium he would announce the advent of the fuzzy design attitude, which “may no longer represent the purity of chemical crystals and the precision of mathematical paths. But it does well represent what is indeed the fuzzy reality of our galaxy, with its evolutionary, nebulous, indeterminate and milky stage, between mass and energy”. (Domus 800, January 1998)

Since the 1990s, however, what had already been one of Branzi’s main themes has firmly returned to the stage front of his thinking: interiors as a landscape, charged with strong architectural, social, artistic and political instances (those we mentioned earlier), blurring all the scale boundaries which used to separate different disciplines.

Interiors means the deconstructed and domesticated offices of “Citizen Office” (the Vitra exhibition created with Sottsass and De Lucchi, which appeared on Domus 751, July 1993) that anticipated Silicon Valley aesthetics and their indoor tennis tables by 15 years. Interiors are the models and installations Branzi has been working on until the 20s, the Dolmen, the Primitive Metropolis, his micro-environments for flowers. A neutral black interior is the space in which Domus has organised an iconic dinner in 2004, where Branzi, Magistretti, Mari, Mendini and Sottsass dived deep In the world of objects (Domus 869, April 2004). The spaces of the Forum for the Arts in Ghent, designed with Toyo Ito (Sponge Forum, Domus 887, December 2005), are an extended interior, merging with the surrounding city in the impalpable wave of a semi-transparent sponge. Interiors as a landscape are the cities themselves, like the Grand Paris that Branzi proposed to be returned to animals in 2008.

Branzi’s interior space par excellence is then both of a physical and mental space for cultural nourishment: the “emotional library” (Unpacking my library: Andrea Branzi, Domus 947, May 2011) that Branzi decided to unpack for Domus in 2011. This has been the stage for one last display of disillusionment towards design and the power of its narratives, when it has come to Céline (“Now, design has to deal with this new ‘end-of-an-age’ feeling, and quit guaranteeing happy endings. It continues to churn out sofas, chairs and lamps instead of wondering about where it’s all going to end”.); still, it has also become an occasion for a definitive cultural statement blended with the sharpest autobiographical synthesis when it has come to Catcher in the Rye: “ Ettore mimicked Salinger a little in the way he wrote. Now I realise that the books I’ve really been influenced by have been novels or poems. I’m sorry, but these aren’t any texts on the theory of design or architecture. On the other hand, they don’t say anything to me. I can’t help it. Even if I try to come up with one, no particularly engaging reading experiences come to mind. Not even Le Corbusier, whom I certainly appreciate for the fibs he was able to tell”.