By Sophie Aliece Hollis

Mario Ballesteros is a Mexico City–based independent curator, editor, and researcher in the fields of design and architecture. Over the last 15 years, he has become a significant force in Mexican design, both elevating emerging talent and celebrating established artists, architects, and designers. He earned his expertise through a series of notable roles: In 2012, he served as the founding Editor in Chief of the Mexican edition of Domus; he served as Director and Chief Curator at Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura (when open, it was the only space in Mexico dedicated to the collection, exhibition, and advancement of design); and in 2019, he was the guest curator of the Abierto Mexicano de Diseño, an open-source festival celebrating designs from over 200 Mexican creatives. Today he serves as cofounder and curatorial director of Salón COSA, a biannual show of contemporary objects that takes place in Mexico City.

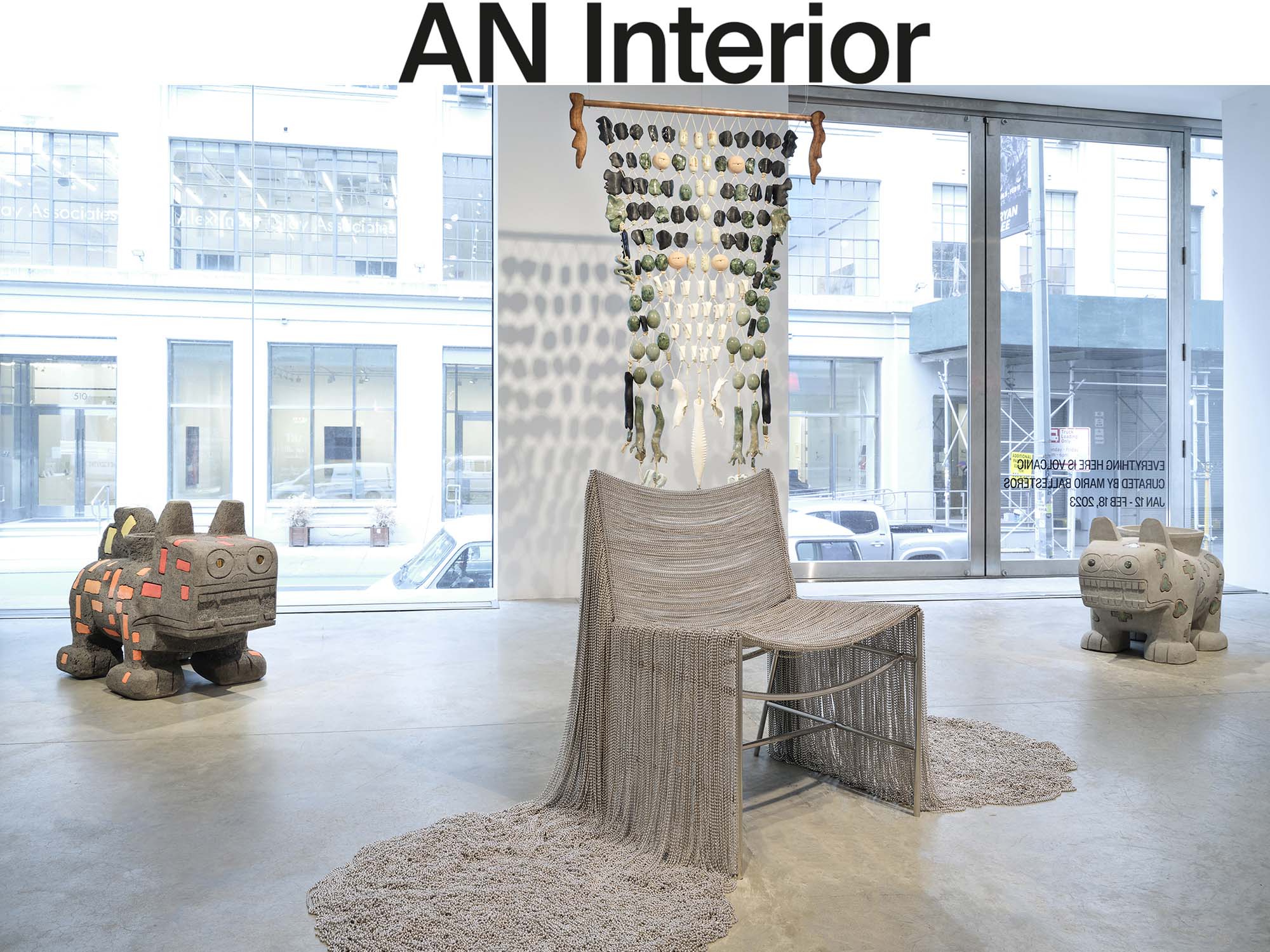

But it doesn’t stop there: This week marks the opening of Ballesteros’ latest exhibition, Everything Here is Volcanic, a celebration of the versatility of Mexican creativity, on view at Friedman Benda New York until February 18. In just a few weeks, Ballesteros will also open his own contemporary design gallery, Ballista, in Mexico City’s Laguna, a rehabilitated industrial space for creatives designed by PRODUCTORA. The gallery will bring together 11 local designers from the fields of design, architecture, art, fashion, and more. Over a coffee in Mexico City’s Condesa neighborhood, AN Interior sat down with Ballesteros to attempt to unpack the state of design in Mexico and discuss his many efforts to further the field in his home country.

Sophie Aliece Hollis: Tell me a little about your background. When did you get involved in design?

Mario Ballesteros: Well, I’m not an architect, even though people assume I am one all the time. I studied international affairs at a liberal arts college in Mexico but later got my master’s in metropolitan and urban studies in Barcelona. Since I was young, I’ve been obsessed with architecture and design, and I’ve tried to find ways to approach design without necessarily being a designer.

A big part of my background is editorial work, so the evolution to curation was pretty natural: As an editor, you’re curating, just in different formats and spaces. In 2012 when I launched the Mexican edition of Domus, I began trying to find out what was going on in design in Mexico. Back then, it was pretty difficult. There was a lot happening in architecture—architecture in Mexico has been an established contemporary practice for a long time—but industrial design was somewhat lagging, mostly because it was still traditional in the way that it’s taught. Industrial design had never been recognized as a form of cultural production; it was always regarded as being concerned with straightforward ergonomics.

Since that work for Domus, I’ve been invested in experimenting with how to approach emerging designers, and that’s still my drive. In the last decade, the general creative industry and design, specifically, has blossomed in Mexico, so much so that I find it even more interesting than what’s going on in architecture.

SAH: Over the last few years, Mexico has become an area of interest to many creatives, and increasingly to international talent. Can you talk a bit about that shift?

MB: Emerging from the pandemic, the city feels much more cosmopolitan, open, and diverse than it did ten or 15 years ago. But the truth is that Mexico City has always been an international city, especially for artists and creatives—it has always been a refuge. If you look at Mexico City after the Mexican Revolution in the 1920s—Tina Modotti, Edward Weston, Leon Trotsky, Hannes Meyer—so many key figures in the contemporary movements of art, design, and photography either lived or spent some time here. The country has always had that sense of international drive. Now I think we’re returning to a moment where it’s more pronounced.

On the other hand, our local culture can be a bit self-centered. It’s so deep, rich, and diverse that sometimes I think we’re so preoccupied with Mexican identity—what makes us Mexican and references to traditional Hispanic craft or pre-Hispanic motifs—that we can lose track of what’s going on elsewhere. That’s problematic because, if we’ve learned anything in the last few years, it’s that Mexico is inevitably connected with the global reality: Everything that impacts everywhere else impacts Mexico as well.

In my recent experience working on this show for Friedman Benda, I’ve had a lot on my mind. Questions like: How can we maintain an understanding of how everything is connected but also continue to value working with very local conditions, problems, and opportunities? How can we avoid those clichés of what it means to be Mexican but also think about what Mexico has to say or can bring to the table? It’s an exciting challenge both for myself and for the artists and designers I’m working with. I think that’s what makes Mexican creative practices feel different. In this very permissive context—you can do things here, with very little money and few legal restrictions—freedom and dynamicity shows. That’s why I think it has become such an attractive place for all sorts of creators.

SAH: The affordability and availability of gorgeous raw materials and high levels of local craftsmanship have certainly been an asset in establishing Mexican design culture. How have you seen industrial design specifically evolve in the last decade or so?

MB: Ten years ago, it was difficult to find well-rounded projects in design, not just because of the designers themselves, but also because there was a lack of interest from editors, curators, and museums. Since then, researchers and academics have done substantial work to try to understand how design can be a contemporary, relevant sphere of cultural production. I was privileged to be a part of that communal effort when I was at Domus and Archivo.

Worldwide interest in Mexican design is happening because we’ve done our homework; we’ve taken the time to really articulate, communicate, and understand what we bring to the table. That was difficult because the country doesn’t really have the support system for young designers in schools that you have in Europe or the U.S., for example. Here, schools are limited in scope, and they promote professional preparedness instead of the more cultural aspects of the practice.

SAH: Does the government do anything to support the design industry?

MB: That’s another challenge. Both arts and architecture, as well as other creative industries like cinema and theater, have had support from the government for a long time. Design is not necessarily considered “culture”; it’s been grouped into the professional industrial sphere, so there’s practically no support from the government for practices or projects. Though it’s changing, and some museums are starting to open up to design exhibitions, there’s no dedicated design museum or institution in Mexico.

SAH: That’s a shame, an institution like that seems so necessary.

MB: Yes, and that’s why Archivo was so incredible. Unfortunately, the project closed a couple of years ago. Even though we were a tiny institution, it filled a void in a short amount of time with few resources. We managed to do about 15 exhibitions, and it really became a space for communities.

The void left when Archivo closed is starting to be filled again, in different ways. Independent projects like Salón COSA, which I launched with my partner Daniela Elbahara two years ago, is an iterant design fair that happens twice a year. A few years ago, there was a huge offering at Abierto Mexicano de Diseño, the Mexican design Open, which I also guest curated 2019. It was a community-driven and -directed event with something like 200 different venues, projects, and people. It was democratic, diverse, and horizontal. In a way, it was trying to counter the more traditional, commercial, industry- and brand-focused design shows, which are equally as important but very different.

SAH: Regarding Everything Here is Volcanic, you said you wanted to challenge what people considered to be Mexican design. How did that goal shape your curatorial process? Did you try to stray away from stereotypes and pick up work that exists outside of what people might think constitutes Mexican design?

MB: Yes. That’s been my intent for a long time. I’ve always been fascinated by the margins of the practice, and I like challenging stereotypes. It’s important now because there’s a big spotlight shining on what’s happening in Mexico, and sometimes that spotlight lands on people who don’t necessarily even live here or speak the language. Or it seems to be limited to a very specific space, usually just a couple of neighborhoods here in Mexico City. That, to me, is a version of Mexico that is a little bit diluted and too comfortable. For me, it was important to demonstrate the diversity of Mexico by focusing on other parts of the country and to do the same thing in terms of the discipline. What really excites me about the show is that it’s a mix—a bunch of misfits, really—like architects that are interested in fashion or designers that are doing art. The show’s participants don’t necessarily stop at labels like “architecture” or “design.” We didn’t want to offer any answers. We’re not saying this is the “real” Mexican design, or this is what you need to expect from design in Mexico. It’s more that we want to free up those assumptions and make people surprised, curious, and wanting to know more.

The works on view are really strong and wild. I love them. They’re totally unexpected, which is something that Friedman Benda always does; They’ve always shared the intention of bringing disciplines beyond their commercial scope. It was a great fit and I feel super fortunate to be collaborating with this incredible venue to present the work of the 15 artists and designers who are in the show.

SAH: How did you get connected with the gallery?

MB: It’s funny, actually. I signed up for a series of virtual lectures during the pandemic in which Mark Benda, the director of the gallery, was one of the speakers. At the end of his lecture, I sent a couple of questions in. Afterwards, he got my contact information from the organizer of the lecture series. We exchanged a few emails, basic stuff like “What do you do? What’s your story?” We had only exchanged about two or three emails before he invited me curate one the gallery’s ninth annual guest-curated exhibition.

SAH: You’ve been working on this show for two years?

MB: Yes. In 2021, Mark came to Mexico, and we visited several of the artists in their studios, which really gave him a sense of the scene’s vibrancy. The show is a bit strange for me, as in Mexico we’re used to working with tiny deadlines and budgets and making ends meet at the last minute. Having a long time to think about this and having more resources at hand was really a very different experience for most of the artists that participated.

SAH: The show’s title comes from a statement by Swiss architect and the second director of the Bauhaus Hannes Meyer. What does it mean to you?

MB: The first time I read that quote was maybe 10 years ago when I was researching for an architecture guide to Mexico City. When I came across it, I was just blown away. It was such a simple sentence that is powerful in an obvious way. This beautiful quote applies to the Mexican landscape, culture, state of design, and overall vibe. Also, this is not a show for experts on Mexico and Mexican culture, so having the title be a phrase from someone from outside of Mexico who lived here, was inspired by the place, and came to understand its versatility is powerful.

On another level, the quote was very important because the show is temporal. The context is super contemporary, but I think if you saw some of the pieces outside of this installation, you might even think they were from an ancient Mexican culture. These pieces speak about the past, present, and future, and they point in all sorts of directions. Bringing this quote from a time of modern cultural effervescence 100 years ago to today as Mexican culture enters the spotlight yet again was the perfect way to encompass what we’re doing.

SAH: Absolutely, and congratulations! That’s very exciting for all involved—especially the less established designers in the group.

MB: Yes, that was very important for me. I didn’t want the show to be about a generation: I didn’t want it to only focus on established and well-known figures. They are important, and there are a couple included, but I definitely tried to level the playing field and give people the opportunity to meet some of the more abstract players in the Mexican creative fabric.

SAH: Can you speak about an emerging talent whom you’re excited about? I noticed a fun spiky stool in the preview photos.

MB: That’s by fashion designer Victor Barragán. We’ve been working together for a couple of years. He wasn’t always in fashion; he actually trained for a bit as an industrial designer. Now he’s interested in returning to a more object-driven practice and I am definitely very excited to have this renewed medium in the show. He is also one of the designers that I will be representing at Ballista.

SAH: Tell me more about Ballista. Is it similar in ambition to Archivo?

MB: In spirit, yes. The only difference is that it needs to be self-sustainable. Archivo was a nonprofit and Ballista is going to be a commercial gallery. That’s a big change for me. I’ve always been more oriented to cultural, nonprofit projects. But I do think it’s important to think about the market and open up financial opportunities for collectible designers in a place like Mexico where it’s difficult to find collectors and galleries. It was somewhat of a natural evolution to really delve completely into this world.

I’m going to be working with 11 artists and designers at Ballista. Some of them are super young—Chuch Estudio, a duo of female designers from Mérida, are 22 and 21. Marcelo Suro recently graduated from SCAD; he’s from Guadalajara, but he’s interning in New York with Misha Kahn. And then there’s Fernando Laposse, who has a more established practice. I’m also working with designers coming from places like Miami, Tijuana, and San Diego. It’s going to be a very diverse group.

SAH: Wow, you’ve really got a lot going on. Where are you hoping all these developments will take you?

MB: I have no idea! It’s hard to plan right now. Things are changing at a pace that is difficult to grasp. I think it’s going to take us five years just to grasp what happened in the last few. In that sense, the Mexican mindset of shorter timelines is incredibly helpful because we are able to adapt to what’s going on. What I’d like to maintain is flexibility: I never want to stop questioning myself and remaining open while staying true to my principles. I can say that after seeing how much the scene has changed in the last five years, I’m super optimistic. I think we’ll continue to see the emergence of a more diverse and sophisticated community with a much broader reach. I would just be happy to continue to be a part of that, wherever it takes us.