by Michael Snyder

When the brothers Humberto and Fernando Campana opened their eponymous design studio Estúdio Campana in São Paulo in 1984, their witty, daring sensibility came as a shock to an architecture scene defined by one of the world’s most robust modernist traditions. Over the last four decades, they’ve invented a language all their own, making furniture with scrap wood and stuffed animals, cast bronze and bubble wrap.

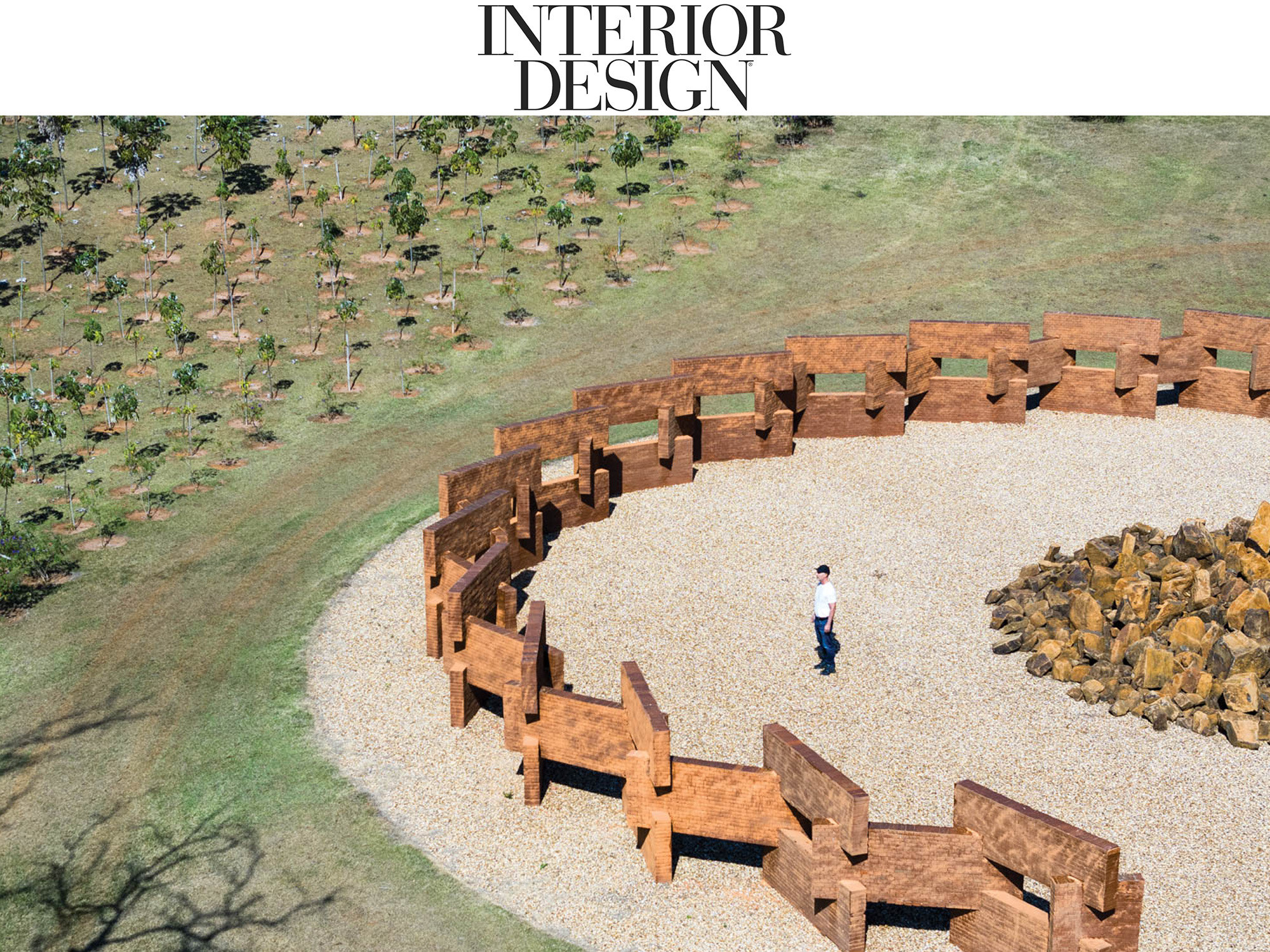

In 2020, the brothers started work on a sprawling, 130-acre park in their rural hometown of Brotas, a 150-mile drive northwest of the city. Since his sibling’s untimely death in 2022 at age 61, Humberto, eight years Fernando’s senior, has thrown himself into that final shared project, slated to soft open in June as a place for conservation and study, but also, like all their work, of provocation and play. As Estúdio Campana looks toward its 40th anniversary, Humberto tells us more.

A CONVERSATION WITH ESTÚDIO CAMPANA ON DESIGN, CONSERVATION, AND MORE

Interior Design: Could you start by talking about how Brotas shaped your work?

Humberto Campana: I was very blessed to have been born and raised there because it has such a beautiful landscape. But at the same time, it was extremely boring, so Fernando and I created our own universe. There was a movie theater that screened American westerns and films from Federico Fellini and Pier Paolo Pasolini and we would recreate the scenery in our yard. We made an unconscious vocabulary that we would only discover years later.

We also avoided being contaminated by modernism. Brazilian architecture has such a strong connection to its modern tradition, but Brazil is much more than that. It’s crazy and colorful, full of texture and even kitsch, and we wanted to bring that into our work. We’re maximalists! We should be proud of all the elements of our cultural heritage.

ID: When you founded the studio, who were your peers and mentors?

HC: My icons were Roberto Burle Marx and Oscar Niemeyer, but especially Lina Bo Bardi. She was a modernist but also interested in the countryside, in our African and Indigenous heritage. She pointed us to Brazil. Fernando and I tried to be industrial designers in the beginning, which at the time meant thinking in terms of utility and mass production, but we failed! We always looked for freedom in our work because we know what it is to live under a dictatorship. Our first exhibition, in 1989, a few years after the dictatorship ended, was called Uncomfortable and it was filled with that anger over all the brutality our country had suffered. Because that’s the real Brazil, too.

ID: How did Parque Campana come into existence?

HC: My grandfather had used this property as a coffee plantation. Later, my father rented it out to cattle ranchers. From the time Fernando and I inherited it, we wanted to use it for conservation, but we were nomads, traveling all over the world, so we kept renting because we didn’t want it to sit there abandoned. When the pandemic came, it put us right back in the countryside and we started thinking: We’ve done workshops all over the world, why not in our hometown?

Growing up, it took almost eight hours to get to Sao Paulo on the unpaved roads, and we would see wolves and jaguars and other animals. Nowadays it’s a desert of sugarcane and soy beans. We wanted to seduce people—the families who work in the agri-businesses that are devastating the environment—with poetry, music, and film. We’ve planted over 16,000 trees, and the idea is to plant more, working with agronomists and environmental engineers.

Then we had the idea to create 12 architectural pavilions (there are six, so far) as spaces where people can have classes, meditate, and watch movies and concerts. There will be an educational program, too, both artistic and environmental, and it’s important for us that all the park’s furniture is produced in the countryside with local materials.

I want to create a school to preserve craft traditions with workshops for welding, weaving, painting, embroidery—all the things we used to have in Brotas when I was a child. Across the world, people are finally giving these crafts the respect they deserve. It’s the right moment to invest in the countryside. Life has been so generous to me and, living in a country with such deep social divisions, I feel it’s time to give back.

ID: What are your future plans for the park? For the practice?

HC: Right now in the park, all the poetry is there, but none of the logistics, so I’m working with a firm in São Paulo to complete all of that. In the studio, we’re working on a documentary that will launch at the Milan Triennale during the Salone and an exhibition at Friedman Benda in New York. I’m also working on a book about our way of thinking and making. But really, I’m focused on opening the park.

ID: Can you speak a bit about how the loss of your brother has affected your practice?

HC: Fernando and I had a wonderful relationship. There was so much trust and respect and intimacy. When I lost him, I felt completely naked, and thought it would be so difficult to keep creating. But I’m actually in a very creative moment right now. Creativity gave me a voice—I came from the countryside, I was supposed to be no one—and now it’s helping me to survive. The park is a memorial, an homage. All the energy I’m investing in it—it’s for him.