By Kat Barandy

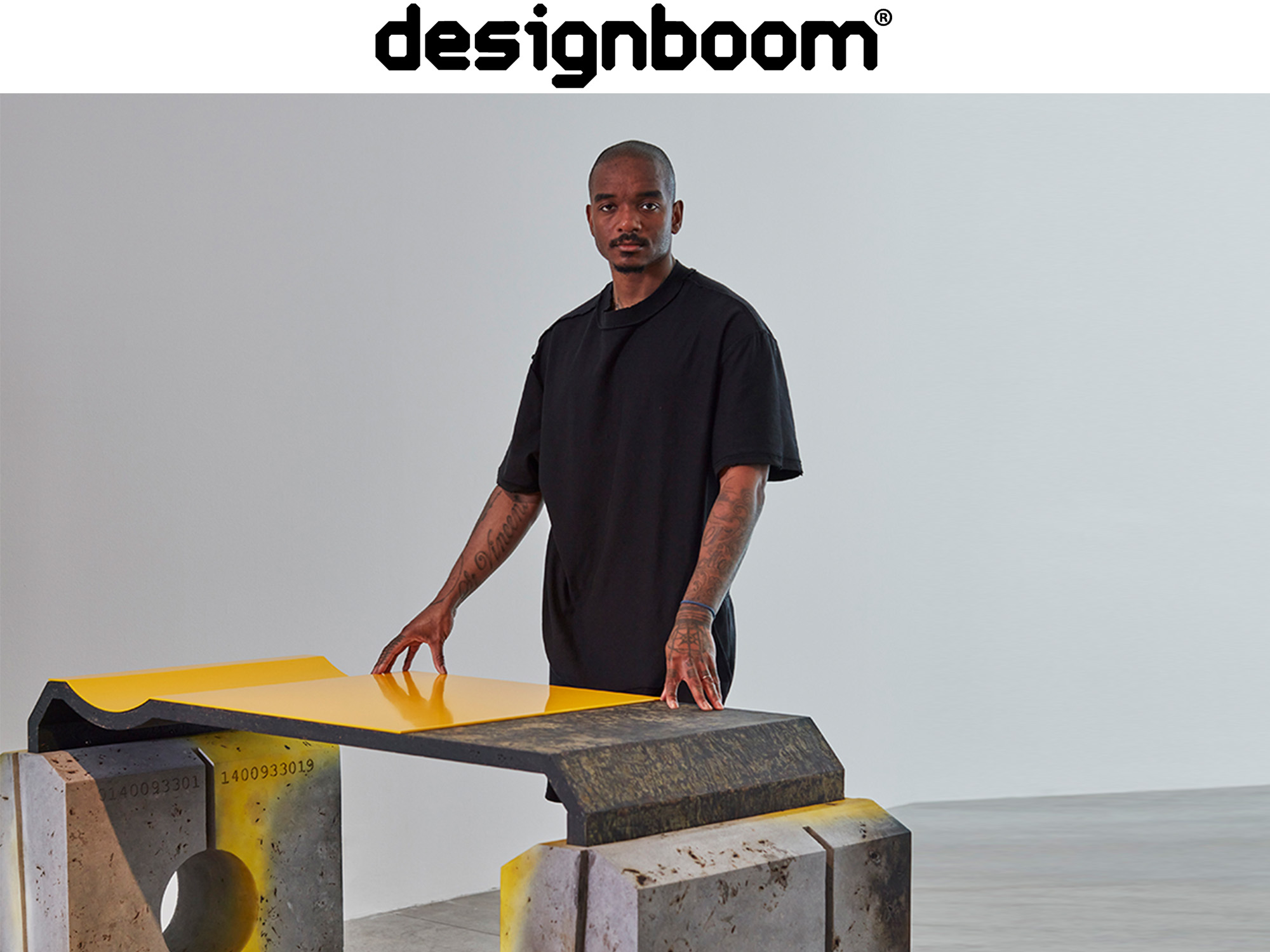

Nestled beneath the High Line in Chelsea at the heart of Manhattan’s creative scene, Friedman Benda‘s New York gallery opens its latest exhibition, ‘COARSE,’ featuring a captivating collection of furniture pieces by British designer, artist, and creative director, Samuel Ross. Making his solo debut in the city, Ross presents his fourth body of work as a raw and layered material exploration.

‘I’m exploring our relationship between the organic experience of engaging with materials, minerals, and fibers that has existed since we began recording art,’ Ross tells designboom in an interview ahead of the opening. The technical precision of furniture design is upended with violent yet meticulous experimentations. The collection sees fired wood, metal, stone, and marble manipulated with turmeric, honey, and milk — early investigations included feces and blood. Industrial materials which were once pristine are now thoughtfully coarse. In time for NYCxDESIGN 2023, ‘COARSE’ will be on view from May 10th — June 17th, 2023 at Friedman Benda Gallery at 515 West 26th Street.

Now on view at Friedman Benda Gallery, ‘COARSE’ spotlights six new works, each an edition of eight, by Samuel Ross. Through pieces like ‘FIRE OPENS STONE’ and ‘ANAESTHESIA,’ the designer explores the intimate relationship between their materials and the human body, while his processes of erosion and celebration of mineral residue leave each piece as an artifact with its own layered history. The object is emphasized as a vessel of memory. In this way, Ross expands the meaning of each piece while preserving its functionality.

designboom met with Samuel Ross at Friedman Benda’s New York gallery ahead of the opening of ‘COARSE.’ The A-COLD-WALL* founder discussed his own layered history, which led him to transcend creative disciplines and move between processes that are intuitive and gestural to intentional and precise.

designboom (DB): What themes are you exploring with this collection?

Samuel Ross (SR): I’m exploring our relationship between the organic experience of engaging with materials, minerals, and fibers that has existed since we began recording art, and working with materials. I’m also exploring the relationship between the synthetic and the idea of postmodern influences through material. It’s really about the tension and the relationship that we have between both of those dimensions existing at the same time for our generation.

DB: You’ve moved between many disciplines from fashion, furniture design, painting, sculpture, and filmmaking. How do you describe yourself?

SR: I would like to view myself possibly as an existentialist, who doesn’t necessarily see a barrier between all of these different modes of communication. So with that comes a deep reverence for each of the disciplines. And the more time I spend between each of those different fields, the more specific my understanding of those fields becomes. So it’s less of an instance where I am trying to touch every surface or pillar. It’s more an instance of understanding the intention and the specialization of each of those particular disciplines to tell particular stories, which are appropriate to the medium.

DB: Did you always know that you would move between disciplines in this way?

SR: I think that the way in which I was raised and schooled in academia, and then the first few years of my professional career, seem to understand the society we were going into. And the requirement to have a level of cross-disciplinary understanding to be able to communicate a message or an emotion. So that organically became a way of thinking, feeling, and speaking for me. What became a curiosity then became a signature.

DB: Can you describe your schooling experience? How much of your skill-set was self taught?

SR: The timeline of my academic life has all these intervals. I was homeschooled by two artists and teachers — my parents — for around four years. I had a pretty standard grammar education in the UK. I then majored in graphic design and illustration at a college level and then at university level, the same major twice. I got a first class degree and was scouted and went into a product design company and then into an advertising agency.

Then, of course, I started working with Virgil and others within that group. There was already a multidisciplinary culture to our work, but I simply view myself as an artist. This obsession with learning has resulted in becoming the youngest Honorary Doctor — Doctor of Arts at Westminster University — which was awarded to me at the age of twenty-nine. Beyond that there’s just a love for learning. I didn’t know that was going to happen. I just love to absorb information and to digest and to read.

DB: I ask because a lot of these disciplines are very technical, especially with fashion design, drafting patterns.

SR: I learned that in factories! So the curiosity of wanting to communicate in garment and fashion started first with a screen print. We were up-cycling and sourcing pre-existing garments, and actually working with tailors and learning about patterns in East London factories — industrial areas such as Leighton or Harrow. We simply spent time with the machinists. I was around twenty-three to twenty-four when this was happening, so two years after the degree.

For furniture, I started learning through craftspeople, makers and machinists. I learned draftsmanship and woodworking, understanding the parameters of what’s capable with material, machining, welding and crafting. That all came through inquiry and spending time with fabricators, carpenters, and with metalworkers over the course of seven or eight years. There were a lot of failures before there was any breakthrough.

DB: How hands-on is your process? Do you still work with sketches, model-making, material experiments?

SR: Absolutely. I’m so glad I can show you some of the sketches. It’s the first time I’ve shown any type of drawing or sketching. We’ve taken about 1,500 sheets of paper, and distilled them down to four. The idea is to show the rhythm of thinking between the process. What I often mediate is gestural work at first to determine a form which then I apply a concept to, which might be like a theory or a philosophy. For example, West African furniture through the lens of modernism, and brutalism.

Then from the abstract point, I try to identify a formal shape in a looser matter, which is why I use either India ink or watercolor to do that, because there’s still a level of fluidity that you get with charcoal. But it forces you to determine the shape. To not complete the process immediately and to kind of challenge where form can go and to bring in serendipity, I move between pen, pencil, charcoal and watercolor, to not have such a rigid way of developing an idea. Because that tension between fine art and furniture in this medium is so close. It’s on the knife’s edge of furniture or fine art. The process of furniture requires a very stern hand with design and draftsmanship.

Some of that thinking is shown here. I’m using ballpoint pens, Burrows, and Fineliners to truly determine a form. For instance, I’m starting to think about the depth of a concave and how the material should work with structural elements like pipe fixtures. You can see the early ideas of different materials coming in, whether it be milk, honey, feces, or blood. Now we didn’t put the last two in fortunately (laughing), but milk, honey and turmeric went into play. And this is really important because it shows the psychology behind the forms where it’s less of: ‘I’m going to design a chair, here’s a chair.’ Instead we need to start from a very abstract, open standpoint and slowly chisel and etch into a final, refined form.

DB: What does your studio space look like?

SR: I have four studios in total! One is dedicated to paint. One is dedicated to industrial furniture. One in London is more like a creative space for A-COLD-WALL*. Then we have the atelier in Milan. Each of those spaces has such a different temperament — it goes back to respecting each of the different disciplines and understanding that they each need their own environment and way of operating.

The home studio for painting and drawing work is not in London. It’s one hundred miles out of London. It’s so quiet and peaceful — we call it ‘The Hole’ — it’s underground. And when you go there, you’re in the middle of nowhere. You can be totally lucid with any type of composition or thinking because there’s no disruption.

The spaces within the city need to be connected to manufacturing and fabrication, and makers that I get advice from in some of the furniture forms and industrial forms. It’s much more of a pristine and accurate space because we’re holding lots of material samples in there. I couldn’t house all of these different ways of working or thinking under one particular roof because they each have a different spirit or soul to what needs to occur.

DB: What have you learned from the previous generations, and what’s something that you’ve learned from this younger generation?

SR: From previous generations, I learned it takes time. And it takes resilience, critique, failure, and success. That dynamic is important to open up the quality of the work, and to broaden a space for your work to partake in the history of the arts and the history of design. You can’t contribute without having risk and exposure. And chiseling away at a practice or a feeling for very long time. You need time.

All of the individuals I may look up to now, or revere, have had on average maybe thirty-five years of a professional career. And they’re only now lauded. That is really important for our generation and the younger generation to remember. It takes a lot of time, and it takes a life. You need to live! What you have to say if you don’t live? There’s nothing to say. So the journey of life is really indicative of the work that we will produce that is of value. You can’t expedite that. One shouldn’t want to expedite it. We’re not machines churning out products, these are artworks.