By Osman Can Yerebakan

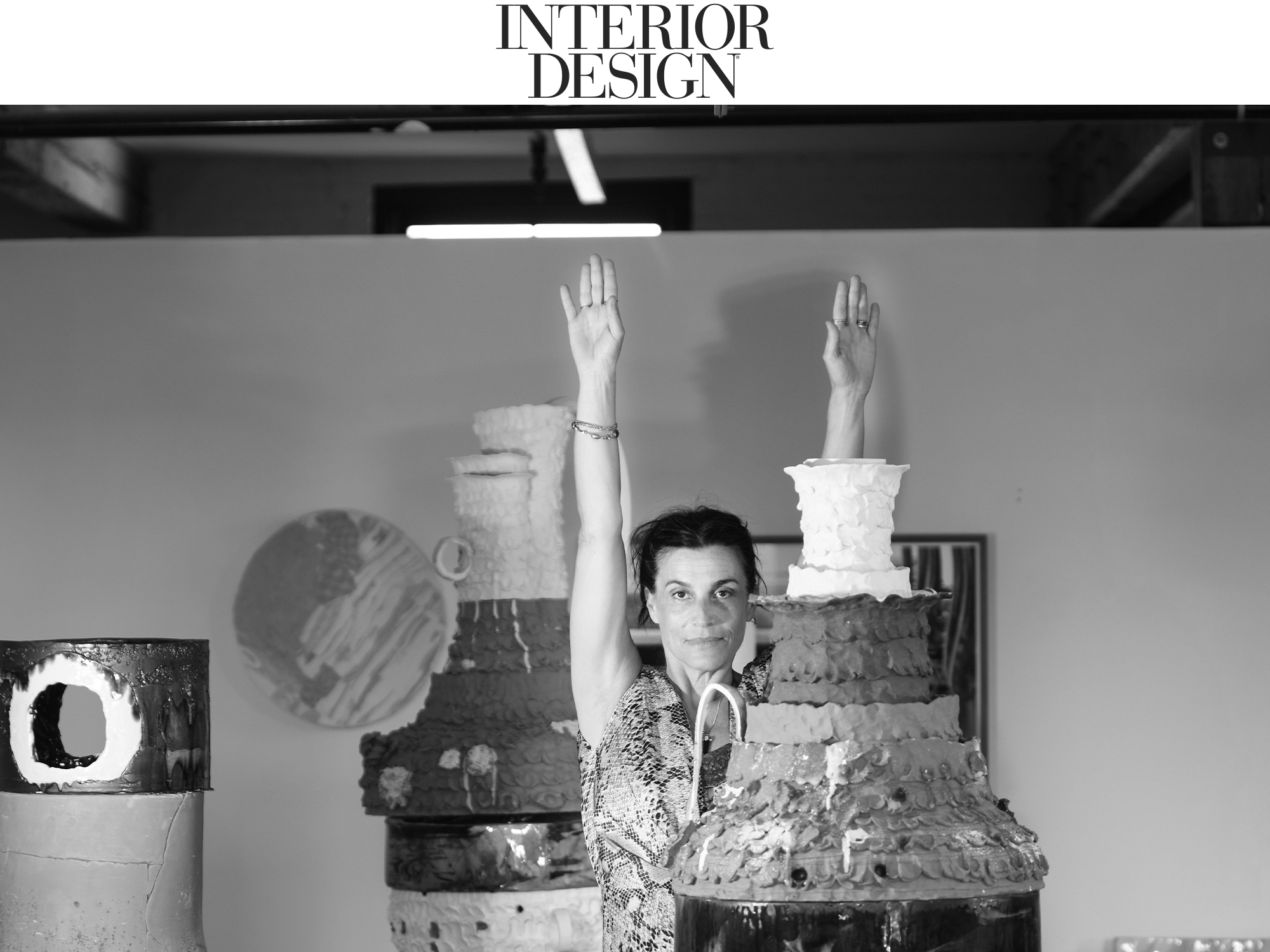

Nicole Cherubini’s new exhibition, Hotel Roma, at Friedman Benda takes cues from a plethora of sources, from seminal novels of female empowerment to the city of Rome. And like the Eternal City itself, the New York-based artist and designer’s three-dimensional works on view alchemize chaos and serenity, with layered textures and dense colorations. Function, intrigue, beauty, and even collapse coexist in vertical clay forms with a sense unexpected bond.

“Every element in my work carries a distinct meaning or reference—from the material and patterns to the cast figurines—layered together to explore the collective weight and visual connections between objects and personal histories,” Cherubini tells Interior Design and adds: “particularly the ways in which objects, and how we are taught to interact with and understand them, shape identity, power dynamics, socio-economics, and societal expectations.”

Storytelling, especially female stories, is a major part of the show’s energetically-colored works. As an avid reader and a sculptor, Cherubini translates her readings into a multidimensional expression. “I use literary discourse almost as a tangible material to help position the concepts behind my practice within a broader theoretical dialogue,” she says. “By incorporating works such as A Room of One’s Own and Down Under, I’m hoping to foreground the agency of women’s voices and writing. These texts (and many others!) become interwoven with visual documentation and my own critical and feminist reflections.”

Working between studios in and out of the city, Cherubini enjoys views of sunsets in Hudson, New York, and lets experimentation guide her practice at her Brooklyn Navy Yard workplace. She explains that the works in the show come from her upstate kiln where large molds yielded the show’s multipart sculptures of equal grandiosity and enigma. “Clay needs constant monitoring—there are many stages of the making—building, drying, firing, glazing, re-constructing, finishing,” she explains. The show will remain on view through February 21, 2026.

Nicole Cherubini Crafts Clay Sculptures Balancing Chaos + Calm

Interior Design: Let’s start with the idea of “dysfunctional,” which is a notion that artists and designers continue to tackle and blur. What is your idea of the functional in creation albeit its opposite as an object of pure aesthetic intrigue?

Nicole Cherubini: I think both these ideas come together through the notion of purpose. For a long time, I had been thinking about denying function through a conceptual framework. But then, I had the realization that it was much more interesting to think about these works, these ideas through the lens of purpose. Purpose gives meaning and agency, it is not taking away anything. Both art and functional objects have deep significance and need in our world; the two are indistinguishable entities.

ID: How did your education in ceramics and fine arts help you blend functional and dysfunctional objects?

NC: I went to RISD as a ceramics major, where I received a strong technical education. I was always a bit of a radical in the department, but I loved working with the material. Clay has historically played an important role in shaping material and cultural hierarchies, especially through its associations with fragility, function, accessibility, and domesticity.

My work subverts these inherited assumptions, especially when it comes to gender. I create clay benches that can be sat on and invite rest and conversation, positioning clay as a structural support for thinkers, not decorative. Conversely, I also produce pots that—through crevices, voids, and overt tactility—reject utility and aesthetic perfection.

ID: Your vessels contain multitudes in the sense that they seem to assemble various ideas of sculpture into singular bodies. Could you talk about this multitude?

NC: Clay is a common material to connect with artists across time, and a lot of what I do is steeped in feminist theory, discourse, and artistic lineage. I work through many of these concepts as I create—as well as my personal identity and experience—which play into the sense of fragmentation you see in the work. At heart, I think I am a collage artist. Even the technical restraints of the material add to this collecting; the process of building to this scale in clay involves multiple parts and sections. The combination of all of this opens up quite a bit of conceptual connection.

ID: In relation to the previous question about multitudes, you use clay in various forms and chemistries. Could you talk about your relationship to clay and how you diversify this relationship?

NC: Clay has so many uses, so many histories, and takes so many forms. Each of them has such specific references. They all hold different conceptual materials. I love taking bits from all of them and collaging them together. This comes in the forms of different colors and types of clay, glazes, forms, etc. From looking at all of these differences, I realized that for my making and my ideas, I needed to push that even further and actually began looking at clay and glaze as disparate materials. The two became unique entities, almost denying ceramics, and object-ness.

ID: Verticality is an important part of your sculptures; they are totemic and stoic and always rest on specific pedestals which are parts of the work. Could you talk about this perpendicular unity among your works?

NC: The verticality comes from the stacking and collaging to make a whole. It is a way to give the sculpture height and elegance. It is uncomfortable to look at a clay object larger than oneself, and even more so when gravity feels tested. The pedestals are another attempt at creating some tension with the viewer. They both deny and reference object-hood by challenging traditional exhibition standards for sculptures, especially ceramic. It is also a call and response; the two parts supporting and completing a thought and in communication.

ID: The new show also has works with dual bases. How did this transition happen?

NC: Working on 46 Gordon, the roving dance performances I have done with choreographer Julia Gleich, has completely transformed how I understand space, and even more so bodies in space. I have always been aware of the role of the viewer in my making, but the work with the dancers has given me clarity in how a viewer actually exists in space, and their connections with objects existing around them. This breaking apart seems like a natural response to this new knowledge—the duality influences how the viewer can see sculpture and the space it occupies.

ID: Butterfly seems to be about unity as much as the balance of divergences. What do you see in the work in terms of experiencing alchemy and harmony?

NC: It is funny that you ask this, and I am so happy that you can see this. Among other ideas within the context discussed here, this piece is a love letter of sorts—maybe almost a portrait of a relationship. It was made for and about someone that I care very dearly for at such a specific moment in time, for both of us. I think this is the first time a work has been so clearly illustrative to me, and at the same time holds so many secrets.

ID: How do you trance between furniture pieces such as chairs and sculptural works at your studio and in your thinking process?

NC: They are a continuous thought. They all come from the same place, the same making, and the same thinking. Their construction is usually generated from the conceptual framework of the exhibition. What do I need to put forth my ideas in the clearest way? How can I offer this to the viewer? For Hotel Roma, for the first time, I combined the two and connected a large sculpture to a 12’ bench.

ID: Your colors are bold, energetic, and contemporary. How do you build your palette and translate it for different exhibitions or series?

NC: I adore color. I love experimenting with it in my studio, and equally love wearing layers of it. Many of the colors come from my study of artifacts. I will see a glaze on a work at a museum, gallery or home and become obsessed with it for both the beauty as well as how it will so vibrantly point to a historical moment. I then work to try to formulate it, to match it, or reproduce it somehow. This always has translation due to available materials, firing techniques, even the water used. It is another tool of the collaging, I guess.

ID: Rome as a city and a cultural signifier contains remnants of antiquity perhaps more than any other place. Chaos and order cohabitate there. Could you talk about what this duality means for the show?

NC: Rome feels less like a single historical moment than a place where time has accumulated, and where meaning is constantly reconsidered. Rather than presenting history, meaning, or medium as something fixed, the exhibition allows these elements to overlap, interrupt one another, speak to the present, and hopefully inform the future.

As the granddaughter of Italian immigrants, I’ve long been fascinated and consumed by the Italian American aesthetic—and how it exists in me as both complete adoration and a wee bit of repulsion. The accumulation of objects and what that reveals from a socioeconomic standpoint is incredibly intriguing. It takes a great deal of privilege to appear minimal or to practice aesthetic restraint. I’m interested in playing with this tension: moving between maximalism and minimalism, Baroque and Modernism, tasteful and ostentatious, surface and form, high and low, art and craft, art and design, and traversing the boundaries that separate them.

ID: As an Elena Ferrante fan myself, I always find the fury in her work unparalleled. What did you find compelling in a group of writers’ work to weave into your three- dimensional work as a sculptor?

NC: Fury is a fantastic word; it so clearly visualizes her intensity of language and experience. I find Ferrante’s writing somewhat brutal, violent, and just blatantly honest. The Lost Daughter, to me, is, by far, the most Bataillian discussion of motherhood I have ever witnessed. All of the authors mentioned in Glenn Adamson’s essay use words to put forth—almost make naked—the visceral experience of womanhood. They elegantly, gracefully, brilliantly, and precisely show the embedded violence of our society. Their language is raw and present. I hope to visually present that to the viewer. I want to somehow make my use of material similar in strength, force, brutality and splendor.