By Glenn Adamson

The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel. – William Gibson, Neuromancer (1984)

Everything seemed to stop there for a moment. The Sex Pistols said it first, or at least loudest: NO FUTURE. Others followed: it was the end of history (Fukuyama), the fall of the grand narrative (Lyotard), the road to nowhere (Byrne). The calendar dates kept coming, increasingly portentously, 1976… 1981… 1984. But there was a persistent feeling of being dislodged from linear time. So said the leading theorists of the day, at any rate. Writers like Jean Baudrillard, Fredric Jameson and David Harvey, diagnosing the ills of late capitalism, found a range of symptoms: time-space compression, the death of authorship, a disconnection between medium and message. It all added up to paralysis for progressive culture. Those who read and believed these claims felt that they stood at some new, bewildering Archimedean point, from which progress looked a cold and distant prospect. It was, as William Gibson intimated in the first line of his cyberpunk novel Neuromancer, a general break in transmission.

Much has been written about this moment in the history of art and architecture; I have contributed to it myself, in a large-scale exhibition at the V&A held in 2011, which I curated with Jane Pavitt.[1] Even so, there is much more to learn about this unsettled period, which offers lessons we might apply to the present day. Particularly deserving of further attention is the era’s “radical design,” a term that aptly captures a commitment to dramatic change. Reacting swiftly and intuitively to the intellectual currents around them, designers came to the conclusion that their longstanding role – to conceive new stylistic forms in the service of commerce – had become irrelevant. Yet they continued to make compelling objects.

[1] Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1970 to 1990 opened at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, in 2011, and thereafter traveled to the MART in Rovereto, Italy, and the Landesmuseum, Zurich.

No doubt we are seeing the end of the myth of progress, which transforms time into a linear function, where everything changes continually. Maybe we are witnessing a return to circular time, that is, a time when everything changes, however without development. – Andrea Branzi [2]

What were the operating principles of radical design? Best known, perhaps, was the widespread recursion to past and found forms: the “postmodern” tendency to raid the closet of history for ideas, to mix and match at will. But the best designers of the era did much more than quote and assemble. They employed deconstruction as a generative methodology, finding liberation in the act of rupture. As Andrea Branzi – an important theorist of radical design, as well as a practitioner – noted, it was by abandoning the fashion cycle, the progressive sequence of styles, that it might be possible to achieve a new aesthetic possibility.

Any narrative of radical design must start in Italy. The ideas were born there due to a combination of factors: a slowed-down economy, which discouraged the usual commercial imperatives; a sophisticated and intellectually-oriented architectural community, which served as a talent pool; and a strong craft infrastructure, which made it possible to realize experimental objects in a diversity of materials.[3] Beginning in the late 1960s, a series of collective groups undertook research into the possibilities of the radical object.

[2] Quoted in Cristina Morozzi, “La poétique de l’équilibre, entretien avec Andrea Branzi,” in Andrea Branzi (Edition Dis Voir, 1997), p. 87; translated in Constance Rubini, Andrea Branzi: Objects and Territories (Bordeaux: Musée des Arts Décoratifs et du Design/Editions Gallimard, 2014), p. 216.

[3] See Catharine Rossi, Crafting Design in Italy: From Post-War to Postmodernism (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015).

In substance, the rejection of production and consumption, the rejection of work, are visualized as an aphysical metaphor: the whole city as a network of energy and communications. – Superstudio, 1972 [4]

Arguably the first of these was Superstudio, a collective formed by Florentine architects in 1966.[5] In a series of films and allegorical objects, the group anticipated a future in which the economic activities of production and consumption would give way entirely to mediation. We would collectively experience “the destruction of objects, the elimination of the city, and the disappearance of work,” and in the place of that traditional economy, “a network of energy and information extending to every properly inhabitable area.” Superstudio’s vision was totalizing, in a way often associated with utopia and dystopia, but it lacked the moral overtones of either. Instead of a heaven or hell on earth, they postulated an endless neutral field, in which “slowly, as on the surface of a mirror, such things as the need to act, mold, transform, give, conserve, modify, [would] come to light.” After this total reinvention of life, the only objects left would be basic necessities (which they called “utensils”) and purely symbolic forms, which functioned like flags or emblems.[6]

Superstudio’s ideas about the future, which doubtless seemed bizarre and improbable at the time, eerily anticipated today’s pervasive and placeless digital technology. This premonitory quality is often seen in radical design. Though made in a spirit of ahistorical finality, these works leapt ahead of themselves; in retrospect, they can be seen as poignant harbingers of our present day. While they are certainly physical things, they capture the moment of their own material disintegration or breakdown. Perhaps the earliest avant garde design object to be made in this spirit was Gunnar Aagaard Anderson’s 1964 chair entitled Portrait of My Mother’s Chesterfield. Like the work of Superstudio, it could be seen in the context of Pop, but its materiality points to a wholly new set of possibilities. Poured in sequential layers of poured polyurethane foam, it is an additive object that nonetheless conveys a sense of deliquescent disappearance. The chair’s poetic title suggests a more personal narrative of ageing and loss. In retrospect, Anderson’s design seems the harbinger of a coming world – which has proved to be our world – in which objects dissolve into a communicative flux, just as Superstudio predicted. Radical design is right at home in the twitchy and insubstantial domain of Instagram.

Superstudio’s template, that of the avant garde collective, would be repeated numerous times in Italy and elsewhere in the 1970s and 1980s. The pattern was much like that of underground music, in which stars formed groups, disbanded them, and migrated amongst them. The biggest impact was achieved by Studio Alchymia, led by Alessandro Mendini, and its more commercial successor Memphis, led by Ettore Sottsass. These two were like the moon and the sun of radical design: one saturnine and cynical, the other enthusiastic and generative. Both were restlessly prolific.

[4] Italy: The New Domestic Landscape (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1972), p. 244.

[5] The members of Superstudio were Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Magris, Roberto Magris, Adolfo Natalini, Alessandro Poli, and Cristiano Toraldo di Franci.

[6] Italy: The New Domestic Landscape (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1972), p. 242-246.

Bit by bit I realize that there is no salvation to transmit, that no generalized identity exists in architecture and our work, that messages are random, that contents are immaterial. – Alessandro Mendini (1980)[7]

In addition to his work as a designer and architect, Mendini was a hyperactive editor, successively leading several magazines (Casabella, Modo and Domus). Alchymia, with its group-sourced and disjunctive forms, reflected this orientation, and so too did his most famous design, the Proust chair, which fused together the disparate references of the Baroque, pointillism, and the French modernist sage of memory into an unforgettable union. If Mendini was something like a pop star, this was his hit single. But if one were to identify a single project by Mendini that most characterized his turn of mind, it might be an installation called Nulla (Nothing) that he staged in Florence in 1984, toward the end of his influential reign as editor at Domus. He explained that the project represented “a total return to zero… nothing real or communicable occurs: it is merely a momentary condensation of energies outside of time, a condition of ‘ornamental vacuum’ soon to disappear.”[8]

If Superstudio’s vision was infinite, and Mendini’s nihilistic, Ettore Sottsass’s might best be described as libidinous. Sottsass was a full generation older than most of the other radical designers (when he founded Memphis in 1981, he was already sixty four) and also had the advantage of long experience in industrial applications. He retained a strong sense of design’s roots in raw desire, even as he fully bought into the anti-commercial and theoretical dispensation of the day – as early as 1972, he wrote of the need to decondition the consumer from “the interminable chain of psycho-erotic self indulgences about ‘possession’,” instead “making furniture from which we feel so detached, so disinterested, and so uninvolved that it is of absolutely no importance to us.”[9] This position would not stop him from pursuing extravagant and sensual effects.

In many respects, Sottsass’s stance embodied the complexity and contradiction of the era. Memphis was intended and received as a stunning assault on norms of taste, yet it was also a clever piece of promotion; one way to interpret the project is as an elaborate product placement scheme for Abet Laminati, one of Sottsass’s important clients, and a financial backer of the initial group of Memphis furniture, which extensively featured their patterned products. Also telling was the fact that the group’s work was issued in annual collections, like a fashion house’s, and that the first batch were all named for luxury hotels (reportedly an idea that came from Sottsass’s partner Barbara Radice, who functioned as a critical voice for the group).

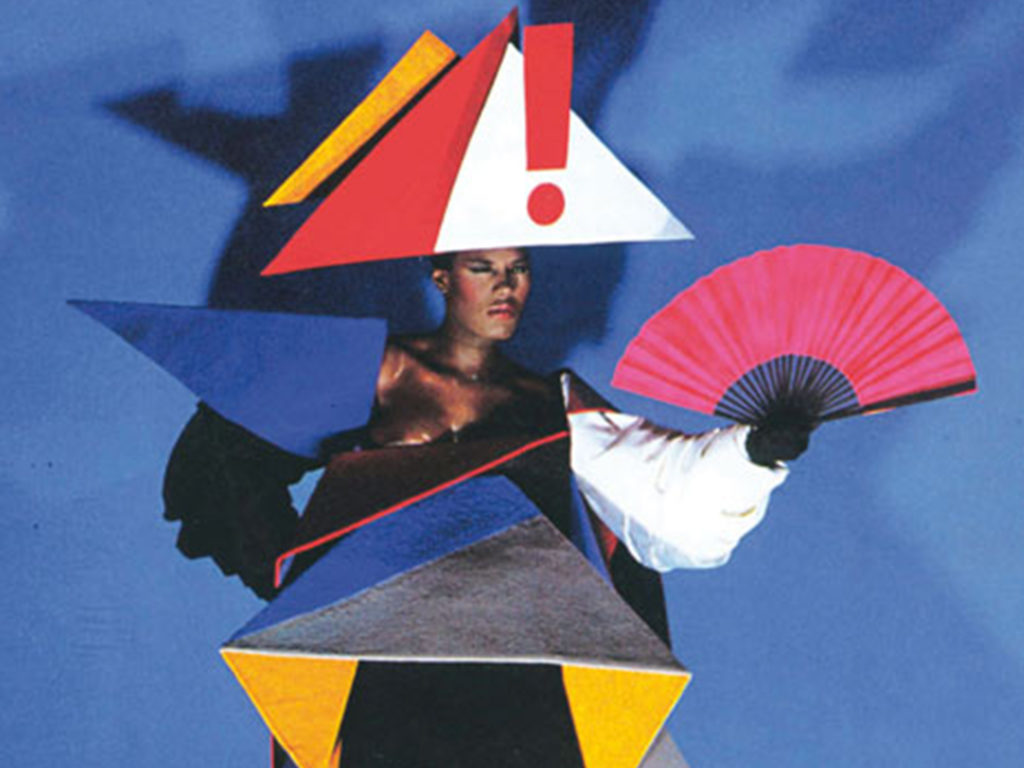

The tactics of Memphis – a series of grand gestures, intended for dramatic effect – were notoriously effective. The collective’s impact could soon be detected in everything from music videos to high street jewelry. By the same token, this was not the most radical of radical design moments. Memphis’s emphasis on the façade prevented a more sustained engagement with the material basis of design and its possible transformation.

As radical design proliferated geographically, however, individual practitioners were undertaking a range of critical projects that did precisely this experimental work. In New York City, there were the adherents of the gallery Art et Industrie, including Howard Meister, whose superflat depictions of imminent collapse are the strongest American equivalents to Mendini’s work. In California, the graphic designer April Greiman provided some of the clearest statements of the period aesthetic, dismantling the grid-based order that had been dictated by modernism, and instead treating the visual field as a domain of slippery, plastic movement. Shiro Kuramata, the only designer who could rival Sottsass as an international figure, pursued a personal and somewhat hermetic course, which nonetheless intersected with currents from Europe in a suggestive way. His works in plastic and glass were the era’s most elegant statements of design’s dematerialization. In Germany, meanwhile, there was an aggressive post-industrial tendency led by the groups Kunstflug and Pentagon – the latter formed by five designers from Cologne. They proclaimed an anarchic, yet pragmatically artisanal point of view: “We need a crisis if we’re to get anything done.”[10]

[7] Alessandro Mendini, editorial, Domus 602 (January 1980); reprinted in Domus IX: 1980-1984 (Cologne: Taschen, 2006), p. 12.

[8] “Nothing: A Dangerous Environment,” Domus 653 (Sept. 1984); reprinted in Domus IX: 1980-1984 (Cologne: Taschen, 2006), p. 550.

[9] Italy: The New Domestic Landscape (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1972), p. 162.

[10] “Denn die Krise ist das immanent Mittel unsere Produktionsweise.” Meyer Voggenreite, in Pentagon: Informal Design (Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag, 1990), p. 29.

“Our work is about contamination: as much as the world contaminates ourselves, we want to contaminate the world.” – Humberto Campana (2008)[11]

Later in the decade, the Campana Brothers would blaze on to the international scene, drawing on a particularly Brazilian mode of improvisatory making. Their neo-Duchampian approach, which involves reclaiming and reconfiguring found materials in unexpected ways, was an early indication of the course that progressive design would soon take. A similar methodology was concurrently pioneered in Britain, where figures like Ron Arad and Danny Lane produced metal-bashing, gate-crashing furniture that earned the popular descriptor “creative salvage.”

This methodology entered the mainstream in the 1990s, as Dutch designers – particularly those affiliated with Droog – abandoned the punk-derived, apocalyptic strains of the previous decade and sought a newly positive and specific engagement with everyday life, via narrative. Having survived its self-imposed near death experience, design was ready to turn outward again via the “assisted readymade” (that is, the altered found object). The possibility of transdisciplinary practice, located equally within art and design, had been implicit in radical design for some time; but it was only toward the end of the 1980s that figures like Michele Oka Doner and Forrest Myers managed to convincingly position themselves in this way. Other concerns crowded in, too – the practical demands of sustainability, the productive possibilities afforded by digital tools. In a word, design moved on.

I don’t believe in static things. I believe that time is liquid, and that realities and values change from one hour to another. – Gaetano Pesce (2013)

Yet certain aspects of radical design have remained in place, not only because the key protagonists have continued to make vital work (Sottsass remained a potent creative force until his death in 2007, and most of the other figures involved remain active today), but also because the extreme positions staked out in the 1970s and 1980s have remained the ground zero on which more recent designers have built their foundations.

If one had to point to a single figure who best encapsulates the trajectory of radical design, Gaetano Pesce would be a good choice. Trained as an architect in Venice, he was involved with the collective Gruppo N even before the days of Superstudio, and has worked for many commercial clients. But his most resonant work has always been intensely individual. While many of his peers have been content to let the political dimension of their work remain implicit, he has always been clear that his work is meant as a physical embodiment of critique. “We are living in an age when values are changing,” he wrote in 1984. “The result is insecurity – insecurity about politics, religion and culture, insecurity about the future of some minorities or ourselves, or about territories, or about the economic situation.” He sought to apply this sense of emergency directly to his designs, as in his Pratt chairs, which were poured from nine different formulas of resin. Some of the resulting forms were rigid enough to be sittable, while others flopped to the floor, dramatizing a sense of collapse. The experiment method fleetingly adopted by Gunnar Aagaard Anderson in the 1960s was, for Pesce, a general principle of operation: “We incorrectly assume stability for a chair, but I want people to think about instability.”[12]

In early 2017, Pesce’s words seem all too prescient. We have just endured an extraordinarily damaging and destabilizing political season, and are likely entering a period of ideological conflict that has not been seen in America and Europe since the late 1960s, the moment when radical design first emerged. Will today’s designers be equally successful in finding forms to suit the times? We can only hope so. Meanwhile, while the extreme propositions of radical design are now themselves part of history, they may still serve as a useful quarry of ideas, forms, and inspiration. Looking back on these objects, which emerged from profound doubt, may be very useful as we seek to change the channel of history once again.

[11] Quoted in Rose Etherton, “Antibodies by the Campana Brothers at Vitra Design Museum,” Dezeen (16 June 2009).

[12] Gaetano Pesce, quoted in Martin Eidelberg, ed, Designed for Delight: Alternative Aspects of Twentieth Century Decorative Arts (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Decorative Arts/Flammarion, 1997), p. 115.

This essay was originally published to accompanying exhibition “Static“, curated by Glenn Adamson for Friedman Benda in New York, in January 2017. A selective core sample of radical design works from the 1960s through the late 1980s, the show was sheathed in a projection of ‘white noise’ and a low-volume hiss of feedback.