by Glenn Adamson

In 2016 Dr. Samuel Ross made a small sculpture possessed of nominal functionality: an incense burner. It ignited something, alright. Alongside his established métier of fashion, propagated through his brand A-COLD-WALL*, Ross began to make and circulate usable objects, and today – seven years later – this aspect of his practice is on fire. Even as his star has risen in the fine art firmament, thanks to the acuity of his abstract sculptures, and more recently, paintings, even as he has become a more and more consequential voice in fashion, he has, in parallel, applied his blazing intelligence to the discipline of furniture.

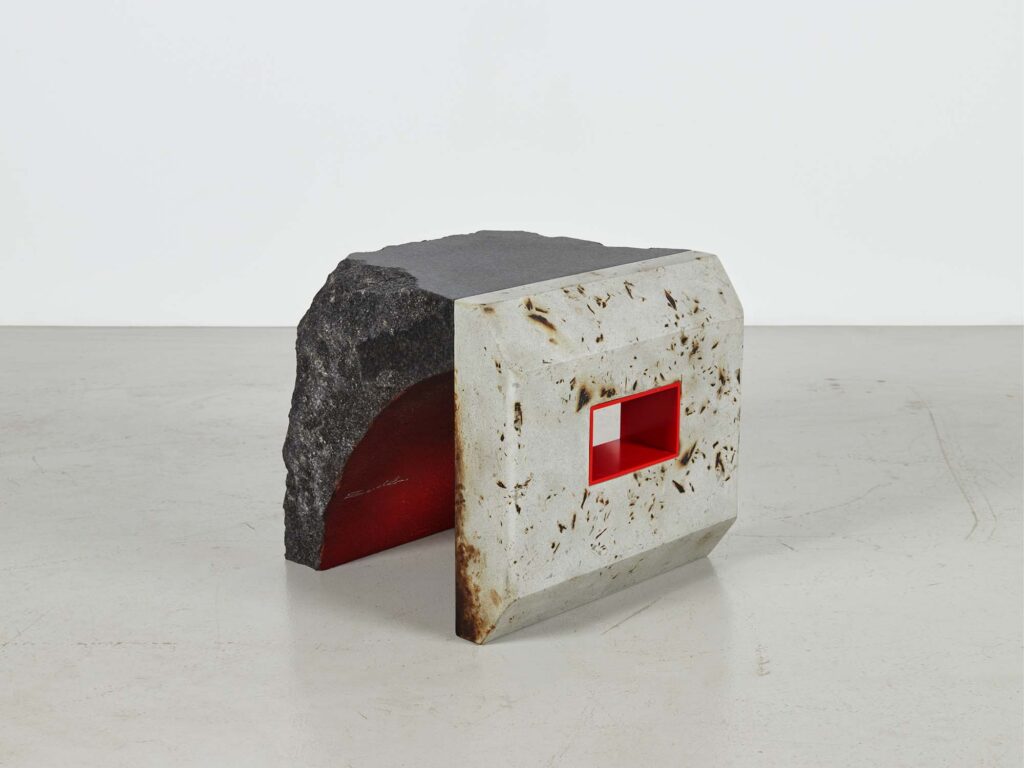

The present exhibition constitutes his most consequential intervention into the field yet. One of their most striking features of the six works on view – straightforwardly acknowledged in the collective title, COARSE – is their jagged, post-industrial materiality. Searingly intense in their conception and execution, they have also been subjected to deconstructive processes. The resulting rough-and-tumble affect recalls that first incense burner, which was made of concrete that was intentionally poorly mixed, giving it the quality of an eroded monument. It’s a theme Ross has been exploring ever since. In 2017, in collaboration with Jobe Burns, he released a series called Concrete Objects. Angular and assertive, they were “specific” in the Donald Judd sense of the term, while also glancing at (and off) British brutalist architecture – so heroic when it was first conceived, but already decaying by the time Ross was growing up among those buildings.

He also materialized this aesthetic in his fashion, which is often post-apocalyptic in appearance: garments exploding outward from the body like shrapnel, trainers pocked and pitted like salvage from a bombsite. Yet this connotation of violence is balanced by an equally evident sense of care in making – a combination of qualities that one normally encounters only in the domain of the relic, a charged category of object that traverses low and high, secular and religious culture. Ross is dexterously triangulating between it all. He alludes to the pervasive cliché of “distressed” clothing, but cross-fades that vocabulary with the midcult genre of cyberpunk, as well the more esoteric discourse of avant garde designers and architects like Gaetano Pesce, Ron Arad, and Arata Isozaki all of whom responded to the utopian heroism of previous generations with ironic gestures of pre-ruination.

Ross has no interest in extending the postmodern endgame, though – he knows that’s all played out. Instead he embraces erosion as a creative force, treating it as simply as one iterative turn within a greater cycle. The apt metaphor here is not collapse (though as earlier works attest, like his TRAUMA CHAIR of 2020, the arc of failed imperialism and its attendant asymmetries are important conceptual geometries in his work), but rather the generative principles of religion and nature, in which death and life continually produce one another, and hence, meaning itself.

Look deeply into the works here, past the initial impression engendered by their concrete, OSB plywood, and powder-coated steel, and you see this spiritual organicism everywhere. Hewn stone – the material of sculpture rather than product design – is an important presence. Ross has treated some of his surfaces with turmeric, the ancient “golden spice,” and others with milk and honey, that Biblical leitmotif of nurturance. It is salient that he grew up in the church, and even pursued theology briefly before entering his career in design; but his work transcends the confines of any organized religion. He speaks of communing with a “wider sentience,” a holistic understanding in which various intelligences are all intermingled: mineral, organic, and industrial.

To this list we can also, perhaps, add the virtual: a critical condition for Ross’s work, as with any designer of his generation. He thinks deeply about the potent new forms of immateriality that have arrived into culture, and how they compare with older ideas of transcendence. Back in 2021, Ross wrote of his own work as situated at “the crossroads and thresholds of the analogue age and the lossless, democratic age of information access.” This position is cued in an unusually explicit way in one work here, titled FIRE OPENS STONE, through the inscription of numerical codes along its chamfered lengths. A tribute to Ross’s former mentor Virgil Abloh – who often deployed text and numerals on his work – the motif also operates on other registers. It’s clearly akin to a bar code, that ubiquitous instrument of social and economic tracking. Could it, perhaps, be interpreted as a sly, self-referential allusion to the furniture’s own commodity status?

Probably so, but more importantly, the digits denote the work’s inhabitation in the digital at large. FIRE OPENS STONE began its life as one of a raft of Ross’s handmade drawings – a fundamental aspect of his practice – and then made its way into physical form via rendering software. This is standard operating procedure in contemporary design, but to an unusual degree, Ross manages to signal every station along the transit. Even when you are standing right in front of the finished piece, you can feel the open-endedness of its inception, while the numbers seem to track its brief passage though the virtual. Thus it arrives like an emissary from a space of infinite possibility: like everything Ross makes, it is both foreboding and thrilling, slightly ahead, something we need to catch up to.

Futurity has been a part of industrial design since its very beginnings, in the 1920s, when the novel idiom of streamlining was developed to telegraph the idea of forward progress. A century on, Ross is carrying on the tradition, but with a big difference. The works in COARSE do have a slight inflection toward science fiction – Blade Runner and its progeny – but are equally rooted in shapes that humans were making thousands of years ago. One of the things Ross aims to erode is the very idea of a “formal timeline.” As he says, that simply isn’t how temporality works in everyday life: “Whether it’s back and forth, or everything happening all at once, it’s interesting to play with this dynamism and rhythm of what is new versus old; what is recognizable now versus what was then… you start congealing these elements which shouldn’t exist together, but do exist within lived experience.”

In this connection, it seems important that Ross’s bench-like forms are all engineered a bit differently. Each gets from one end to the other in its own fashion. In ANAESTHESIA I, the top arches across two identical blocks. In SLAB, also nearly symmetrical, two masses are penetrated by a cylindrical core. BORDER, a work in scorched wenge (a tropical hardwood), is more irregular in plan; it touches down lightly, spread across six dainty feet. By contrast, BIRTH AT DAWN, very compressed, is comprised simply of a curved piece abutting a vertical slab. Of the many metaphors that collide in these works, this simple fact of diversity is perhaps the most significant. Each piece travels along its individual vector, finding its unique solution.

Ross, then, makes no pretense to having cracked the code of the now. On the contrary, the supreme clarity of his work allows us to feel, really feel, just how complex, layered, multivalent, and – yes – enigmatic an object must be, if it’s to express its own time. His exploration of this dynamic is unmatched; his work marks nothing less than a new maturity, a new sophistication, in design. What Ross is making is, indeed, a bridge to the future. But having crossed over, we’ll each of us need to go our own way, on to the ever-elusive horizon.

This essay was originally published in exhibition catalogue Samuel Ross: Coarse, Friedman Benda, New York, NY, June 2023.