By Glenn Adamson

I’m not really trying to make timeless objects – just trying to make things that keep track of what it feels like to be alive right this second. – Misha Kahn

How does it feel out there, on the very precipice of the present? Most of us don’t even think to ask. We surround ourselves with what is familiar, settling into each day as if it were a pair of old socks. Newness has its attractions, of course. But only in strictly limited dosages, and as formulated by someone else – a specialist in what’s happening now. To such emissaries of the contemporary, we reserve the name of “artist.”

At least, that’s how a lot of people used to think. The ideal of the avant garde, perched bravely on the prow of history: it was a grand tradition. But surely it has become irrelevant today. Today, when novelty is the coin of the realm, the currency of everything, our pathetic addiction, our special curse. Already fifty years ago, the artist Robert Smithson observed that change, if sufficiently rapid, could paradoxically come to feel like paralysis: “actions swirl around one so fast they appear inactive… Direct political action becomes a matter of trying to pick poison out of boiling stew.” (Hard to believe that wasn’t written in 2020.) This leaves for the artist – what? Just stirring the pot? Smithson didn’t quite say, though the spiraling vortex of his work was an answer, of a kind. In the half-century since, the problem has only metastasized. What does it means to be new, now? Do we still hold a special place for the creative soul – the special being who lights the world on fire? Or is it all just flotsam, so much junk twisting into an ocean gyre?

Dizzying thoughts like these always seem to come up for me, when I think about Misha Kahn. It’s easy to say, and many have, that he is the ultimate millennial designer. Voice of his generation. Furniture design’s answer to Ryan Trecartin and Lady Gaga. A one-man macrotrend. Since graduating from RISD in 2011, his rise has been meteoric, fueled partly by his personal charisma but primarily by his prolific, associative imagination. Yet for all that he is a genuine phenomenon, it would be dead wrong to stereotype him as just the Next Big Thing, recklessly chasing novelty for its own sake. Kahn has described this newest exhibition at Friedman Benda as “earnest and classical.” I would like to take him at his word.

We might start with the title: Soft Bodies, Hard Spaces. If that sounds to you like it has something to do with modernist architecture, you’re exactly right. Rather like the kid at the end of The Emperor’s New Clothes (“but he’s wearing nothing at all!”) Kahn has a talent for seeing clearly through cultural pretensions. For him, it is really deeply strange that we humans, squishy and irregular as we are, spend so much of our time in inflexible rectangles. “What teen girls feel about magazines,” Kahn says, “I feel about the built environment. It’s like body dysmorphia.” And he makes another, related observation: even as we’re throwing up giant boxes to live and work in, we put figural sculpture and anthropomorphic design objects in them, presumably to mirror ourselves. But these objects look like people only on the outside. What about their innards? If we are going to take the trouble to shape the objects around us in our own image, shouldn’t we go all the way?

Allow this thought process to zoom ahead to its semi-logical conclusion, as Kahn always does with his brainwaves, and you arrive at some of the shapes in his current work: friendly enough, yet spilling their guts. And already here, in this particular alleyway in the complex map of his thinking, we see how Kahn both is and is not deeply concerned with the now. On the one hand he looks around him – say, in New York City – and is bemused by what he sees. Spaces don’t come much harder than Hudson Yards, for example, the newly completed and widely loathed mega-development just a few blocks north of Friedman Benda. Like a lot of people, he hates the soulless repetitive surfaces he sees in such places: “I think it creates bad energy for humans to see replicas of anything, and we’re already subject to so much of this (like bricks or sidewalk blocks or cars or most things). It creates both the idea of infinite resources and personal insufficiency simultaneously.” He is trying to provide an alternative. This is what lies behind the wild formal variation in his work, his aversion to straight lines and serial units. He wants to refuse the logic of endless availability: “you can’t just take as much as you want.”

So on the one hand, Kahn is reacting to his contemporary environment, and like any powerful designer, proposing ways that we all might live differently. At one point we were standing in his studio, surveying the glorious wreckage of his exhibition that was still rising into being. “Design could have developed this way already, it just didn’t,” he said. “But it’s not too late!” Let’s not stray too far down this path, though. Kahn may be a rebel of sorts, but he is not setting himself up to critique anything or anyone else, in the approved avant garde manner. His work is too contingent, too particular in every sense of the word, to exist on anything but its own highly individualistic terms. To inhabit a Misha Kahn environment completely, you would actually need to be Misha Kahn.

It’s this radical, even solipsistic individualism that has helped him evade the impasse that Robert Smithson described half a century ago – what eventually become recognizable as the postmodern dilemma, in which gyrations of style lose their significance, becoming a “free play of signifiers” (as they used to say when I was in graduate school). But that’s not a problem if you can create a world of self-reference, with its own semiotic gravity field. That is what Kahn has done. Step one: construct the world. Step two: populate it with objects. You may take or leave them, as you like. He will keep going regardless. This modus operandi is very much of our moment. It is intrinsic to the overlapping genres of virtual reality, video gaming, and social media, all of which involve the construction of elaborate realities alternative to our own, though touching here and there.

The difference is that Kahn is creating his microcosm on his own, using procedures of his own devising. He shows us what the twenty-first century would look like if it were not being served up cold, by corporations. Here it helps to have at least a little grasp of the making processes that Kahn employs. This is a large topic in its own right, as he is involved in so many different materials and techniques. There are certain tendencies that cross this polymorphous spectrum, though, the most important being a habit of transmutation. Almost always, in the genesis of his objects, something soft has become hard, or vice versa. Something trashy is refined – or, again, vice versa.

His first series, titled Heyerdahl after the intrepid ocean voyager, involved sewing together plastic forms and ramming them full of pigmented concrete, which he allowed to cure inside the bag mold. During the hardening process, he had to constantly but slowly manipulate the form so that it would be evenly filled, a movement he compares to “a yoga sun dance.” The result retains the puckered seams of the sewn sleeve, but is perfectly rigid. Subsequently he developed a related series that he called Kon Tiki (after Thor Heyerdahl’s most famous book). These are made by filling a sewn bag with cotton, then taking a mold off that surface, then using the mold to create an aluminum casting. In this way he completed a loop, “materials being cast in a regular way to imitate materials being cast in an irregular way.”

Another body of work, entitled Claymation, reflects Kahn’s interest in biomorphic Surrealism – the work of Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, or the early Alberto Giacometti – as well as recent animation, including the cartoon Ren & Stimpy (which aired from 1991 to 1995, when was growing up in Minnesota). This high-low cultural mixology is particularly evident in the protrusions he includes here and there in the pieces, which could be interpreted either as sinister Surrealist figuration, or comical lolling tongues, or even trailing drool. For all the pseudo-slapstick, though, the Claymation works are possessed of considerable formal intelligence. The interplay of thickly modeled passages with a slender armature of rods, and occasional unexpected moment of elegance – a polished sphere held aloft by a curling tentacle – make for complex and energetic compositions.

The Claymation pieces were originally made using traditional techniques – hand-sketching followed by small maquettes to test the forms, then a full-sized model, then a mold, then the final casting. Recently however, Kahn has begun using a VR tool called Oracle Medium, which allows him to shape forms in digital space. This has so many advantages that he likens it to a “cheat code” in a video game. First of all it’s fast, particularly because the blobby forms that Kahn is using are very natural to the program. “It’s hard to do straight lines,” he says, “but it wants fantasy. It’s like, please, make me a monster.” In Oracle, he can slide right past the hesitations he might otherwise have in taking a stupid risk: he can try anything, and if he doesn’t like it, just click once to undo it. Also, intriguingly, VR has no gravity. The forms can hover in midair, be moved around, cut and pasted. It’s like you’re God, making sculpture. And as Kahn points out with sincere appreciation, you can even do it lying in bed.

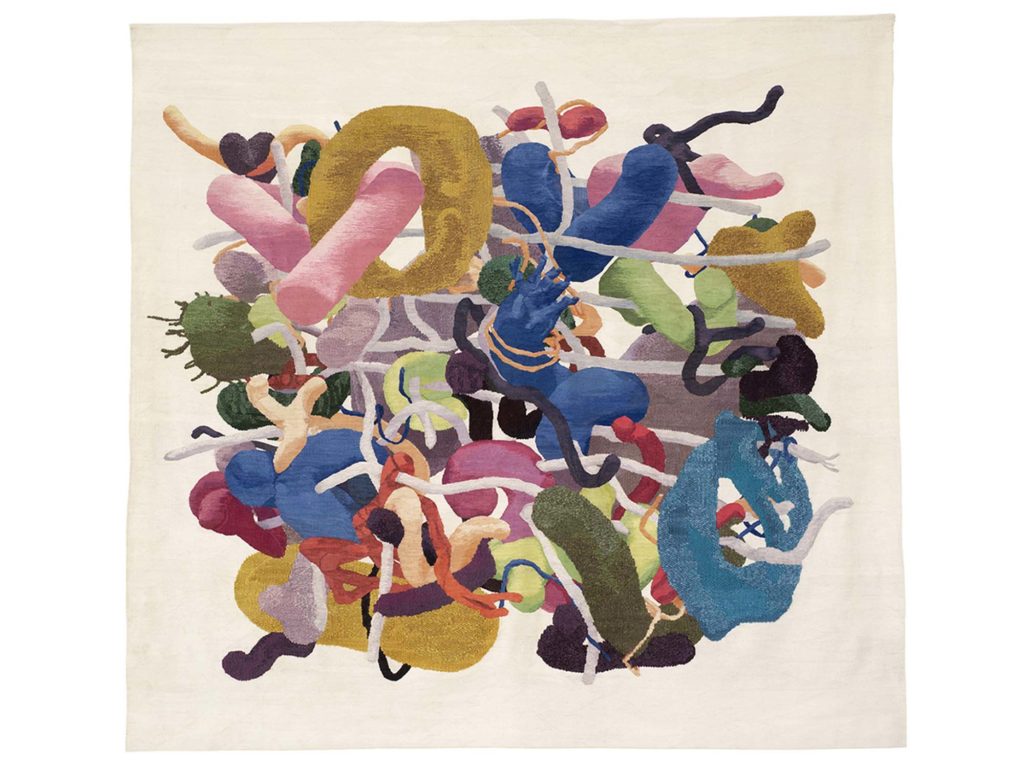

The danger of using a digital tool like this, of course, is path dependency. We’ve all seen them, in profusion: the objects that look like they were generated by a piece of software, rather than a human being. And as Kahn gladly admits, “every kid in America can sculpt these same type of things.” But here’s where his interest in transmutation comes in again. Once he has the rendering how he wants it, he executes a physical model of its constituent parts, either through 3D printing or CNC-carving, and then casts those elements in wax. At this point the forms become analog, and take on new life, “sitting in the sun, getting dinged up, or tossed around in the sand pit.” Finally they are cast in metal, at massive scale, and assembled – not exactly a typical suburban kid’s undertaking. In so doing, he is mating one of the newest artistic technologies to one of the oldest. (“It makes a bridge between worlds,” he says. “Good furniture can take you on a trip.”) A comparable application of this idea is seen in A Loose Understanding of the Space-Time Continuum, a tapestry that Khan designed on Oculus and then had woven at the Stephens Tapestry Studio in Swaziland. The image is flat, obviously, but it features an illusory push-pull of abstract squiggles, which pass over and under one another in a complex snarl. The “real” matrix of the textile is entangled, visually and conceptually, with both the depicted tangle of forms and the “hyper-real” digital realm in which they were spawned.

Perhaps coincidentally, the tapestry also looks a little like a high-resolution scan of brain tissue. Stand in front of it, or any of Kahn’s creations, and you can almost hear the snap, crackle and pop of synapses firing. And this brings us back, inevitably, to the question of his contemporaneity. As should now be clear, this is not really a matter of style. Kahn may have gone digital (a little), but to walk through his exhibition is to navigate numerous accumulated pasts: Surrealism and Art Deco, tiki bars and Tommy Bahama shirts, classical sculpture and classic sci fi. What makes Kahn such a compelling avatar of the present is his ability to mix all this together, at Google-ish speed, put it in the blender of his imagination, and lend this unruly miscellany the quality of subjectivity that all great art needs, not just to reflect its time, but to transcend it. All this was leading to him, here and now, all along. Sow the wind. Reap the whirlwind. Repeat.

This essay was originally published in exhibition catalogue Misha Kahn: Soft Bodies, Hard Space, Friedman Benda, New York, NY, February 2020.